The following is adapted from a talk I gave at Plymouth Church in Seattle in February 2024.

Good afternoon. I’m honored to be here with you all.

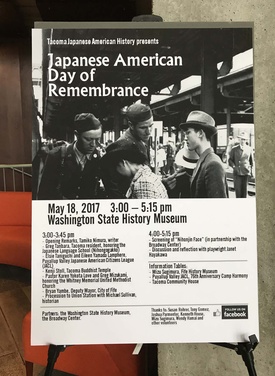

I’m an Asian American writer from Tacoma, half-Filipina American, half-Japanese American. I have so many emotions being with you here today on this day before a national Japanese American Day of Remembrance. This commemoration began in Seattle back on Thanksgiving weekend in 1978, when a group of Asian American activists, many of them Japanese American descendants of Japanese Americans imprisoned during World War II, decided to pull together a demonstration.

A caravan. A spectacle, designed to bring attention to a growing movement for redress and reparations for their families who were unjustly incarcerated. The activists and families gathered at the old Seattle Pilots Stadium, just a little over two and a half miles from here, and it’s now a Lowe’s store on Rainier Avenue South. They drove by caravan down close to my hometown to the Washington State Fairgrounds in Puyallup.

The fairgrounds in Puyallup—that’s where many of my Seattle-area Japanese American friends and community members and elders and beloved survivors are right now, gathering to resist, to rededicate ourselves to the work of remembering Japanese American wartime incarceration.

I knew that I would be missing that gathering, but I was talking to my dear friend, Pastor Karen Yokota Love of Blaine Memorial UMC. And she reminded me that while our Japanese American Day of Remembrance is for our community, it is also important to bring our Japanese American history to other communities as well.

I’m missing that gathering, and I am very glad to be here.

I called this talk “How do we remember Japanese American history?” because I wanted to talk to you all about the ways that America has remembered—and forgotten—Japanese American history, especially the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans.

So: how do we remember Japanese American history?

First I want to talk to you about why I remember Japanese American history.

There’s a picture that I use to begin many of my talks about Japanese American history. It’s the only picture I have of my father Taku and his parents and all of his siblings. My grandparents, Junichi and Shizuko Nimura, were both immigrants from Hiroshima, Japan. They had six children who lived from infancy. There’s an infant in my auntie’s arms—that’s my oldest cousin. And there’s a young Japanese American man in the front, at the left—that’s my uncle who married into my family. But with the exception of those two people, everyone in this picture was imprisoned during World War II, including my father, who was only 10 years old at the time.

My father died when I was ten years old. So when I think about why I remember Japanese American history, especially this chapter of Japanese American history, I think about my dad, and I think about his siblings—most of whom are still alive today.

I’m a descendant of people who were imprisoned, and it’s taken me decades to think in these terms—that my family members were wartime prisoners, that my dad and his siblings were all United States citizens, and they were imprisoned without due process or trial—simply because they were Japanese American. My dad and his siblings were children, most of them 18 and under, enduring hardship and separation from my grandfather, who was arrested in front of his family from within the prison camp at Tule Lake, California.

I have so many emotions about these facts—sadness, pain, anger at the injustice—and a deep pride in the survival of my family and community. A yearning that’s never quite satisfied, a deep desire to keep my dad close by trying to tell his story and his history. And a resolve to let their stories continue to have meaning and purpose within and beyond our community.

This is why I remember Japanese American history.

The title of my talk, though, is a question.

How do we remember Japanese American history? And of course Japanese American history is broader and wider and deeper than the chapter of wartime incarceration. However, as my friend Vince Schleitwiler—professor of American Ethnic Studies at UW Seattle—likes to say, the story of our community’s wartime incarceration is still being told. It is still unfolding.

There are many cases where wartime incarceration—or, in Japanese American shorthand—camp—is a paragraph in a history textbook. Sometimes, it’s a page. It was a paragraph when I was in high school in California, and I was surprised to see even a page in my kids’ social studies textbooks in middle school here in Washington State. Both states which were profoundly affected by the forced removal of Japanese Americans during World War II. For other parts of the country, such as the Midwest or the East Coast, camp history is not even a part of the textbooks or the curriculum. I was just talking to my friend, artist NaOmi Shintani, about her artwork on exhibit at Towson University in Baltimore, Maryland, and she said that most of her audience seemed to not have known anything about the incarceration at all.

So we have places in our country where—despite the imprisonment of over 125,000 persons of Japanese descent, two thirds of them American citizens—the largest mass violation of constitutional rights in United States history—camp history is either erased or ignored. And even then—in states like Washington, which were deeply changed by Japanese American incarceration—there are people that I meet who are unaware of its existence, or the scope, or the injustice.

This is why I made the title of my talk a question. For some, the story of Japanese American wartime incarceration is new. For others, the story is a blip on the radar of American history. For descendants like me, the story of Japanese American wartime incarceration is one that we keep repeating over and over in many different ways, many different modes—exhibits, historical markers, novels, poems, documentaries, Broadway plays, free curriculum, history books, graphic novels like the one I co-authored with Seattle journalist Frank Abe, We Hereby Refuse. So many Japanese Americans that I know have dedicated huge swaths of our lives to telling the story of Japanese American wartime incarceration, and yet there are so many people who don’t know very much. And most of our beloved living survivors of the incarceration now, like my aunties and my uncle, were young children when it happened.

So in some ways, it is a genuine question: how do we remember Japanese American history? If we have tried to tell the story—and really, there are more than 125,000 possible stories—what will it take to remember Japanese American history? What does remembering look like, not only for those who were there, but for their descendants, and for our broader communities?

There are many ways that I’ve worked on keeping this history alive and in different media, but I want to focus today on just three.

The first way that I have tried to remember this history is through writing. Here’s an example, a poem that I wrote, called “Instructions to Persons of Japanese Ancestry.”

I’m an occasional poet—my first training in writing is poetry, my home genre is the essay. Even in longer works, I think I work towards distilling a moment—that’s the poet training.

I wanted to take you behind the scenes of this poem, then. The poem is called “Instructions to Persons of Japanese Ancestry,” titled after the poster which was tacked up on telephone poles and in public places up and down the West Coast. It’s a poster that I’d grown up seeing as I learned more about the incarceration.

I was inspired to write this poem by my friend, the Native poet Deborah Miranda, who has ties to the Seattle area. She wrote an erasure poem based on the writings of Father Junipero Serra, who was one of the main architects of Spanish colonization and missionization. It’s a found poem, or an erasure poem, depending on who you talk to. I wanted to know if I could also use this technique on the poster.

Working with the language of the poster was painful—I had never really stopped to read it closely before. But in gathering what spoke to me, and making it into a letter to my daughters, I found a form of reclamation and healing.

One of the words repeated the most was “family.”

Taking the language of restriction (what will not be permitted) and changing it into what will be taken, permitted, allowed, what will remain, was incredibly moving.

These are the words that resonated with me.

This reclaiming is one way that I have remembered Japanese American history.

Another way that I have tried to remember this history is through public memorials and exhibits.

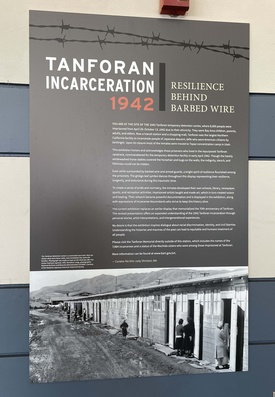

Here’s a picture of an exhibit in San Bruno, California, south of San Francisco. I worked with my friend, artist NaOmi Judy Shintani, to create a permanent 25-foot long exhibit about the temporary detention center called Tanforan where close to 8,000 people were imprisoned for months. Our exhibit is inside the Bay Area Rapid Transit station, or BART.

There’s also a memorial just outside the station, where descendants and survivors have installed a memorial with statues and plaques and so on.

NaOmi and I spent months on the exhibit, maybe even a year, to tell the story of Tanforan through historical writing, photography, visual art, and poetry. The station is next to a shopping mall.

What’s interesting to me, though, as a descendant and as someone who’s worked to write history about that site, is that the stories we have worked to tell in the station and outside the station are very different from the story that the mall owners have decided to tell.

Inside the mall there’s a historical mural with a timeline of the history of the site, paying attention to Tanforan’s purpose as a race track for horses and cars.

There is nothing on that mural about the months that the horse stalls were transformed into barracks, when the walls and horse manure were hastily whitewashed, just barely papering over the insects. When the grandstand was transformed into living quarters for Japanese Americans.

How do we remember the history of incarceration at that site with two such different accounts?

One of the things I learned about that exhibit, though, is that it can be activated with tours, with guides showing people the exhibits and how and where to pay attention. There was an opening ceremony for the exhibit, but there were also guided tours that happened a few times after that.

Otherwise, the exhibit risks becoming fancy wallpaper, another feature that people rush past in their daily travels. We can create objects: markers, plaques, exhibits, and they’re important—but without ways of asking people to notice them regularly, they are tricky.

A museum is only as alive as the people who visit it.

Preservation is another way that I’ve worked with remembering Japanese American history.

And finally, I have tried to work with gatherings.

I’ve helped to create walking tours of Tacoma’s historic Japantown, where the Asian supermarket Uwajimaya began.

I’ve gone on pilgrimage with community members and family to the site where my family was imprisoned during World War II. Every year or every two years, Japanese Americans travel to the physical sites of imprisonment.

What I learned about going on pilgrimage is too much to detail here, but it’s something that I deal with at length in my book, A Place For What We Lose. I can tell you that freedom looks different when seen from within a dusty jail constructed by inmates. Gathering in community, visiting places where history happened—there’s an energy that gets created when place and story meet. The magical equation, as my friend and historian Michael Sullivan explains, goes something like this— Place + Story = Memory and Meaning.

And I would add the element under all of these elements, which is People.

People are what drives stories, people are the ones who have memory and meaning.

And as my husband Josh Parmenter says, there is no technology of memory like the living.

There are also fantastic activist Japanese American groups now who are taking their grief and righteous anger and expansive solidarity about their family and community history, and they are channeling it into activism on behalf of other groups. Right now, today, there are Japanese Americans working on behalf of Palestine and asking for a permanent ceasefire; there are Japanese Americans who have stood near our border where migrants are being “detained,” asking for better living conditions and an end to imprisonment; there are Japanese Americans who are working on reparations for African Americans. These are ways that we can think about remembering Japanese American history—transforming memory into solidarity and action.

Gathering and action, bringing our past in conversation with oppression in the present, is another way that we have remembered Japanese American history.

I’ve talked about reclamation, about preservation, about gathering and action and solidarity. So my question, then, becomes one with a different emphasis: how do WE remember Japanese American history? “WE” being an inclusive term, a broad term?

I look forward to hearing how your families and communities remember their history, and how we can all remember Japanese American history, as we forge new paths towards collective liberation and justice.

Thank you for having me here.

© 2024 Tamiko Nimura