In Cuba there is a long history of descendants of Japanese citizens, and this places them within the global Nikkei community. Cuban Nikkei express the desire to know their history and their belonging to the group of other descendants who, in many places around the world, keep a nostalgic collective memory, conscious or unconscious, that links them to the imagined and intangible Japan, the land of their ancestors.

Although everything indicates that the Caribbean was not included in the plans for emigration and the creation of colonies agreed upon by Japan with some governments of the American world from the Meiji Era onwards, on September 9, 1898, a Japanese man from Mexico arrived at the port of the Cuban capital with the intention of settling there. 1 This event has been taken as the official date to mark the beginning of immigration of citizens of Japan to the Cuban archipelago.

Following the culmination of a long struggle against Spanish colonialism for independence and the abolition of slavery, the Republic of Cuba was inaugurated on May 20, 1902. The ruling elite immediately issued laws that encouraged the entry of European immigrants as settlers and severely restricted the entry of Africans and Asians, whom they classified as unwanted immigrants.

The growth of the sugar industry, the country's main economic source, forced the Cuban government to temporarily authorize the importation of immigrants as a cheap labor force, and a massive influx of thousands of Afro-descendants from nearby Antillean islands, citizens of Asia and other parts of the world took place. Within this immense wave of arrivals were the Japanese, legally or clandestinely, the vast majority of whom were destined for agricultural work in sugar production.

From the first years of the 20th century, a discrete number of Japanese immigrants was recorded, which gradually increased until reaching its highest point in the second decade, and then declined until practically disappearing at the beginning of the 1940s of the same century . During this period of time, it is estimated that between 1,000 and 1,300 immigrants from Japan were able to enter.

These overseas Japanese will form the founding core of the Cuban Nikkei community. They came mainly from the southern areas of the Japanese archipelago, with a numerical predominance of those from Okinawa, Hiroshima and Kumamoto. To a lesser extent there will be representation from other regions of Japan and a few re-emigrants from other countries.

Learning about the quick riches that could be achieved in Cuba encouraged many Japanese to undertake the long journey. They were generally motivated by the same reasons and showed a similar pattern of behavior as other compatriots who came to the Americas at the time: to get rich and return to their homeland. Most were men who traveled alone, very few with their wives or accompanied by another family member.

They are all surprised by the harsh reality of having arrived in a country shaken by continuous political and economic crises, racial conflicts, military interventions by the United States, and threats due to the constant changes in Cuban immigration laws where expulsion was always present. Defenseless against the harsh Caribbean climate, the inhumane system of work in the sugar cane fields, and the insecurity of wage payments, they quickly decide to break their contracts and look for other options for survival in rural areas or in the cities.

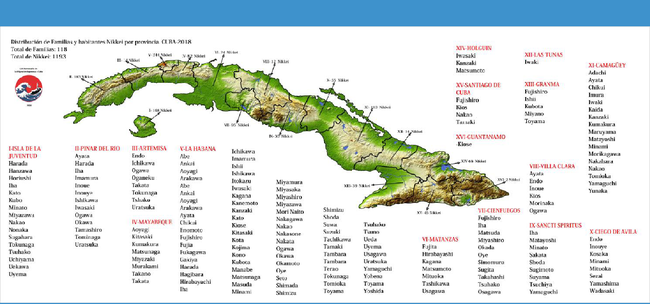

To do this, they learn the most diverse trades, in which they gain the image of tireless workers, and they will go in all directions of Cuban geography, some even crossing the sea and reaching the nearby Isle of Pines. This behavior differentiates them from other immigrants who generally settle permanently in specific regions of the country, so that, despite their small number on the Cuban demographic map, compared to other ethnic groups, the Japanese leave their mark throughout Cuba.

Almost all Japanese immigrants had in common the humility of their origins, but due to their regional origin they were culturally diverse. Even those from the Deep South show phenotypic differences, so it is difficult to speak of homogeneity, but in the new context the symbolism of the concept of “Japanese origin” gains strength, which blurs differences and the defense of the ethical principles of that archaic Japan from which they came prevails as a distinctive banner.

The struggle for survival was the priority. Despite their efforts, it was practically impossible to preserve the identity content of their material culture, to create Japanese schools for children, to send the Nisei to study in Japan, to preserve the language and the close ties with relatives in the homeland. Nevertheless, they used all resources to preserve endogamy. For this reason we find marriages between relatives, brides by order and great differences in age between spouses. It was somewhat easier to preserve what was possible of their culture in the few places inhabited by larger groups. An example of this was the community of descendants of the Isle of Pines, which even had, from early times, a regional association.

For obvious reasons, the Japanese shared the same hardships as the most deprived Cubans and foreigners in society, both in rural and urban areas, from their arrival. With them, they established, in an expeditious, conscious or unconscious manner, active and integrative sociocultural exchanges at a vital moment in the formative process of the national identity of one of the most mixed countries on the Latin American continent.

The outbreak of World War II turned the Japanese into “war enemies” of the Cubans, as Cuba and Japan were antagonistic contenders during the war. Virtually the entire adult male population was sentenced to internment. Although there were no deportations, almost all the property of families of Japanese origin was confiscated and in many cases destroyed.

At the end of the war, they were the last to be released from confinement. Many of the Japanese then went alone or with their families along new routes to places they had never imagined, to start again from scratch, with the certainty that a return to Japan was becoming increasingly distant. Perhaps from then on, the founding core of the Nikkei community began to consider Cuba as a land of adoption.

The second half of the 20th century was a period full of important and decisive political and economic events for Cuba that had a crucial impact on the lives of Nikkei families, 3 which, as an active part of Cuban society, established a consistent, dynamic and integrative historical-cultural dialogue that involved a rethinking of their life plans that had a different impact on each of them.

During this period, other factors occurred that marked the characterization of the Cuban Nikkei community. Among them: the increase in the number of exogamous marriages, the progressive natural disappearance of the Issei, the almost total loss of the language among the members of the new generations, the little or no communication with relatives in Japan, the nonexistence of Japanese companies or industries in Cuba that could bring Japanese workers with them, the inability to create Nikkei organizations, as well as the total interruption of immigration. Regarding the characteristics of the Cuban Nikkei community, the prestigious researcher Alberto J. Matsumoto has expressed: “The Cuban Nikkei have a history and a trajectory different from the Nikkei of other Latin American countries and live in a very peculiar social environment.” 4

The Nikkei community in Cuba has its own narrow framework, so its composition is homogeneous and five generations belong to it. In Cuba, being Nikkei is simply being a descendant of Japanese. This is where the whole plurality of its meaning is contained. There are no additional requirements to be a member of the community of descendants. In this sense, there has been no need to build alternatives of identity resistance for the purpose of social privileges. Within our community there are no conflicts or exclusions regarding economic status, nor in relation to biological miscegenation, nor with exogamy and its degrees; only the Cuban and the Japanese past coexist, without borders, in an indissoluble bond to which we subscribe and fight to preserve .

* * * * *

Notes

- Rolando Álvarez and Marta Guzmán, Japanese in Cuba , No. 17 (The Living Source, Fernando Ortiz Foundation: Havana, 2002), 13.

- See Álvarez and Guzmán, Japanese in Cuba , 25–26; “The Japanese Presence in Cuba,” Centenary of the Beginning of Relations between Cuba and Japan (Fernando Ortiz Foundation, Havana: 2002, foldout); Adolfo Laborde, “The Japanese Immigration Policy Towards Latin America ,” Virtual Legal Library of the Legal Institute of UNAM, 513.

- In 2021: 1,119 Nikkei belonging to 115 families see Nikkei of Cuba. Informative Magazine of Japanese Culture for the Nikkei of Cuba , October 31, 2021, 3rd edition, 5.

- Alberto J. Matsumoto, The Next Generation Situation Study 2018: Part 3 – Nikkei de Cuba , Discover Nikkei , July 17, 2020.

© 2024 Lidia Sánchez Fujishiro