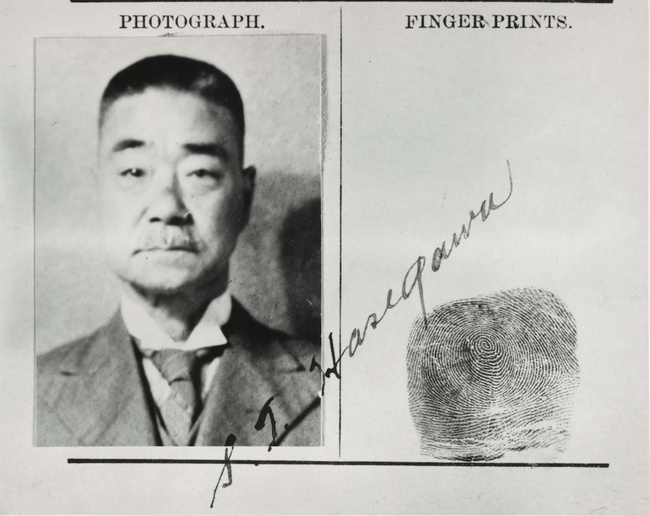

Setsutaro Hasegawa

When Setsutaro Hasegawa died on October 4, 1952, the Australian Hasegawa family’s relationship with Japan became paper-thin. At the height of the northern hemisphere summer, in August, when Japanese pay homage to their ancestors, no one gathers at his grave. Japanese tradition was lost before it was ever gained. It was an era when it was easier to deny your heritage than to acknowledge it.

Grandpa Hasegawa knew who he was. There was no confusion triggered by internment, war, and 55 years living in Australia. He died a proud Japanese man. In 1942, when he fronted a tribunal seeking an early release from internment, he was asked whether he was a patriotic Japanese, he didn’t hesitate to reply: “Naturally.”

Grandpa Hasegawa was born on December 24, 1871 to Setsuzo Hasegawa, a public servant from Niigata, and Matsu Koike of Tokyo. His birth was registered in the port town of Otaru in Hokkaido. He was the eldest son and was with the expectation that he would look after his parents and, under the laws of primogeniture inherit, the family estate, which he did in 1907.

At some point he headed to Tokyo to pursue his education. Details are scant, but we know he lived there. There is not a single document in Australia—marriage certificate, death certificate, or any of the documents associated with internment—where he acknowledges Otaru as his city of birth. In the six months prior to departure, he lived in Kobe. After finishing his education, he became a school teacher.

Late 1896 or early 1897, he boarded the steamer Yamashiro-maru and arrived in Australia on February 12, 1897, aged 26. He came to Australia to learn English, initially working for Arthur Tuckett, a businessman who hired young Japanese men to work as home-helpers. Passports were confiscated and the workers underpaid, a familiar story even 124 years later. Grandpa Hasegawa didn’t stay an employee of the Tuckett household for long; he reclaimed his passport and continued his Australian adventure.

Japanese often found themselves working in laundries and then setting them up and managing them themselves. Why were so many Japanese in Australia involved in the laundry business? Because barriers to entry were low. You didn’t need a lot of capital to set one up, the capital equipment was Japanese, standards in Japanese laundries were higher than in local ones, giving them a competitive advantage, and then there was the Confucian work ethic. Grandpa Hasegawa became a laundryman by accident. That he stayed in Australia for the rest of his life was also an accident.

In 1905 Grandpa Hasegawa married Ada Cole, and later in the same year their first child, Leo Takeshi, was born. In 1907, the second son Moto Kozo arrived, followed by Joe Gonzo in 1911.

Around 1910 Grandpa and family moved to the inland town of Ballarat where he set up a laundry. What motivated him to move from Geelong to Ballarat is unclear, but he lived there until around 1914.

In the local newspaper, he and wife Ada are recorded as winning prizes at dog and poultry shows. He was not shy about involving himself in local activities and was probably the only or one of very few Japanese in town at that time.

In 1913 he made an application to be naturalized as an Australian citizen. It was rejected because “natives of Asia are not eligible.”

At some point his wife left him. I puzzled over when this had happened for decades. In the inreview record at the Alien Tribunal in 1942, he said he had not seen her for twenty years, suggesting the early 1920s; then a distant relative and great granddaughter of Ada told us that she had given birth to a child in 1915 and another one in 1917, leading me to conclude that sometime around 1913–14 Grandpa Hasegawa had become a single parent.

He moved back to Melbourne and was recorded as living with his tailor and friend Ichizo Sato in 1916, before returning to Geelong and sharing accommodation with another lifelong friend, Motoshiro Ito. In the Hasegawa family there are no stories about those times; Grandpa did not share his emotions or talk about what happened. Geelong then became the family’s permanent home until his death.

During cross-examination at the Alien Tribunal in 1942, Grandpa Hasegawa told his inquisitor that he had not had contact with his family in Japan for more than thirty years. The family register indicates his father died in 1907 and that he became the head of the household that year. There are a couple of photos of his mother, sisters and other family members that date from the early twentieth century.

There was no sign of his father, and around the same time an elegant photo of Grandpa and family was taken in Geelong. I speculate that at some point he broached the subject of why retuning home was difficult and his mother cut him off, because he could not fulfil his duties as eldest son.

Adrift, alone and a single father of three sons, he battled on without complaint. His economic situation changed from stable to comfortable in the mid-1920s. I wondered about this for many years and then one day the penny dropped; he had sold the assets that belonged to him in Japan under the laws of inheritance and become a man of means.

He bought a house and owned the freehold of the business he operated in a prime location in central Geelong. There was a car and some other landholdings, and the youngest son, Joe Gonzo, was sent to an exclusive private school in Geelong. Life was comfortable and, as one of my aunts says, it was the “good times.”

Internment

The good times ended December 8, 1941, when the police knocked on the door of 21 Little Ryrie Street and arrested Setsutaro Hasegawa. He was just short of his seventieth birthday. The laundry closed, the family’s economic situation deteriorated, and being a Hasegawa went from a matter of no concern to one of heightened self-awareness. By the end of the war, just when you might have thought things would improve, they became more difficult.

Grandpa Hasegawa was not a gregarious community character. He was happy tending to his Japanese garden, breeding goldfish and birds. He was the patriarch of the house and meals did not begin until he was seated. After dinner he retired to his room and studied, read, and kept diaries. He knew that if you wanted to breed goldfish with certain characteristics, you had to understand how to do it, so you bought a book.

During cross-examination, his good friend George Taro Furuya was asked in what language he spoke to Hasegawa: Japanese, of course. One of the tribunal panel comments on Grandpa’s English language skills and how good they were. My aunt said that when speaking with him in English there was no “accent” or feeling that he was struggling to understand.

Identity Crisis

The seeds of the Hasegawa family identity crisis were planted during the Pacific War, and what followed was oppressive. Capturing the mood of the moment in words is not easy. During the Pacific War, parts of northern Australia were bombed, Japanese soldiers came within 32 km of Port Moresby, and tens of thousands of Australian soldiers found themselves prisoners of war in Southeast Asia. The death rate in the camps was just short of 30 percent.

In September and October 1945, 14,000 POWs returned home with tales of death and atrocities in the camps. Amongst those who returned home were those who were mentally and physically ill, who often led short lives as a result. Of those who recovered and returned to a “normal life,” there were those who forgave and those who remained bitter.

My Aunt Matsu, the second eldest daughter of Leo Takeshi and granddaughter of Grandpa Hasegawa, remembered the forties and fifties with bitterness. At school she was persecuted and had rocks thrown at her because of her Nikkei heritage. Outside of the family, she was known as Sue. When my mother considered naming my younger sister with a Japanese name in the early sixties, Aunty Matsu intervened and told her, “You must not do it.” My mother heeded her advice and named my sister Elizabeth.

Aunty Matsu once told me that she occasionally ran into people she had been to school with when she was young, and if they approached her to start a conversation, she could not “look them in the eye”; such were her memories of those times. Matsu was conflicted by her love for her grandfather and her difficulty dealing with her Japanese heritage. She was a good cook; my cousins tell me she often made Japanese food and was partial to Japanese pickles. In the 1990s, when being part-Japanese had stopped being a burden, she was my guest in Tokyo, enjoying what she had to hide for so long: her Japanese heritage.

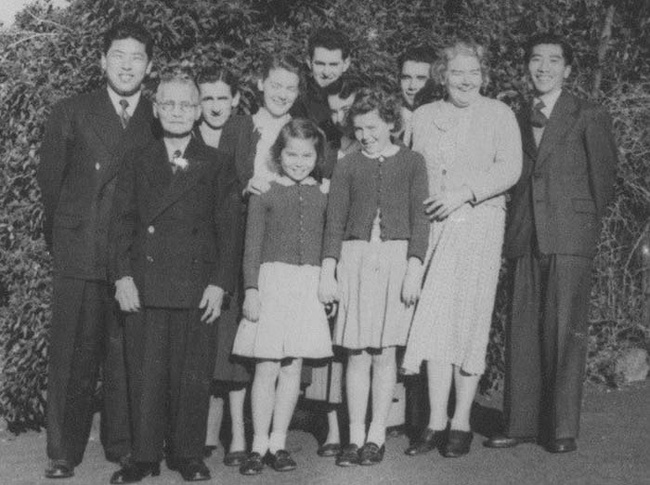

The Hasegawa family house was located in central Geelong and my grandmother, Grandpa’s daughter-in-law, knew just about everyone. So it was no surprise when, in 1953, three hungry, lonely Japanese students studying wool classing at the Gordon Institute were introduced to the family. In the Hasegawa household, they found food and friendship.

One of the students was Hironoshin Furuhashi, a former world record holder in the 1500 meter swimming event and an Olympian. He was later the Japanese Swimming Federation President until his death in 2009. His experience in Australia in 1953 captured the intensity of the hatred towards Japanese in some quarters. In swim-crazy Australia, state swimming associations banned him from swimming in competitions. The racist attitude of these associations was prominent in the print media at the time, but not everyone agreed and eventually he was allowed to swim.

In a brief online biography, Furuhashi mentions the deep hostility of some Australians towards him and the troubles he had finding accommodation because he was Japanese.

The Hasegawa family’s encounter with Furuhashi is still talked about to this day, emphasizing that deep down, most in the family were proud of their grandfather and their Japanese heritage but unsure of how to deal with it. My father, a keen amateur swimmer, often talked about “the flying fish,” while his younger sister still displays a beautiful Japanese doll sent by Furuhashi to the Hasegawa family following his return to Japan. In a hostile environment Furuhashi and the doll became—and still are—a family symbol of connection to Japan.

All photos are courtesy of the author.

© 2021 Andrew Hasegawa