By the time I was born in the early 1960s, the long shadow of World War Two was starting to fade. The 1950s and ’60s saw wave after wave of immigrants arrive in Australia but almost no Asians or Japanese. The white Australia policy still prevailed and if the colour of my skin was anything to go by it succeeded, however I still had my Japanese name.

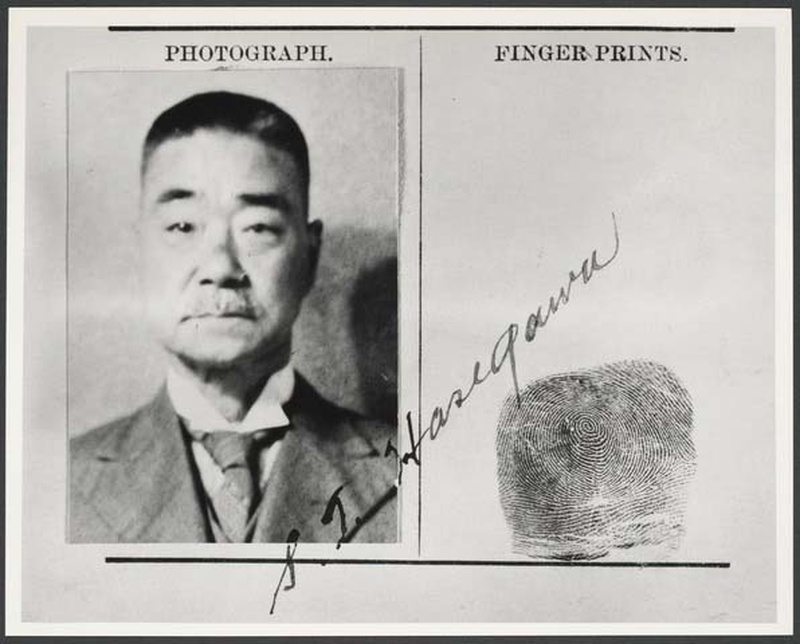

My father was born Raymond Taro Hasegawa, son of Leo Takeshi Hasegawa and grandson of Setsutaro Hasegawa (ST Hasegawa), a Japanese immigrant to Australia who had arrived in 1897 prior to federation and the enactment of the immigration restriction bill, known as “white Australia”.

I never met ST Hasegawa, as he often signed himself, as he passed away in 1952 at the ripe old age of 81. However I do know that he was born in Otaru, Hokkaido, was a school teacher and eldest son. Like many of his generation he took advantage of the freedom to travel that came following the end of the Tokugawa era and the enactment of the Meiji reforms. He arrived in Australia on the Yamashiro Maru in 1897 to work as a houseboy in Melbourne and learn English. He later left the service of his employer and started to work in laundries before setting up his own in the city of Geelong. By 1905 he was married and the first of three boys was born.

In some respects I think the marriage and the arrival of three sons were instrumental in keeping ST Hasegawa in Australia until he died rather than returning home. As the eldest son it would have been expected that he would care for his family, as tradition dictated, but by 1911 he was father to three boys and by 1914 a single parent.

Leo Takeshi, Moto Kozo, and Joe were all born with the surname Hasegawa but only one of them died with it. It seems that life ran along a rather straight path for the Hasegawa family in Geelong until the outbreak of WW2. All that changed the day after Pearl Harbour was bombed and war declared on Japan, when ST Hasegawa was arrested and interned at Tatura. At the same time, Leo Takeshi joined the army, while Moto Kozo worked in Melbourne and Joe was as an accountant.

The children of Leo Takeshi, of which there were eight, lived with ST Hasegawa in the house he had bought in the 1920s. WW2 was a difficult time, the name Hasegawa along with Asian looks brought the worst out in some people but not all. My Aunt Matsu, a teenager during the war tells of stones being thrown at her because of her Japanese heritage. While in Melbourne, Moto Kozo, had had enough of being called a “Jap” and decided that the easiest thing for him and his family was to adopt his long lost mother’s maiden name, Cole.

ST Hasegawa now in his seventies secured an early release from Tatura on compassionate grounds in 1943. He was subject to restrictions but allowed to live with his family at 21 Little Ryrie Street for the rest of the war.

In the modern world we watch television, listen to music, surf the web, and travel. In the pre-television and internet eras ST Hasegawa passed his time when not working, gardening and breeding gold fish and birds. The house in Little Ryrie St had a fine Japanese style rock garden in the front yard, while the back was full of fishponds and birdcages. Family legend has it that people from far and wide came to see the garden.

In those days if you wanted Japanese food you had to walk down to the wharves in Geelong when the Japanese ships were in town to buy wool and barter with Japanese sailors. It is said that while ST Hasegawa was still alive that there were always Japanese pickles in the house. The Japanese community in Geelong was tiny and consisted of 4 men who, along with my great grandfather, married Australian women and ran laundries. They would, I am told, gather on a regular basis to chat in Japanese.

By the time I arrived in the 1960s the Japanese garden at Little Ryrie St had fallen into neglect. The fishponds were empty, the birdcages long gone, and the memory of ST Hasegawa had all but faded. In 1956 after his father died the youngest son Joe changed his name to Cole and purged the memory of a Japanese heritage. Leo, my grandfather, kept his name until his death as did his three sons. Matsu, daughter of Leo, was known to most as Sue, the second and third generation and those around them were often uncomfortable with the idea of Japanese heritage.

I often wonder why it was me, the 4th generation who became interested in my Japanese heritage. In hindsight, I can see there is no one reason but rather many. My curiosity started at home as my father had gathered various items that had belonged to his grandfather, including his passport, pocket watch, abacus, and other. As a little boy I can remember him showing me these family treasures and talking about his grandfather. It left an impression on me and along the way I became more and more curious. At face value I was a little boy growing up in the white Anglo western district of Victoria who looked just like them, on the other hand I didn’t.

It was also an era when attitudes to Japan were in transition, namely it was going from pariah state to being our biggest trading partner and a source of great interest as its consumer goods, animation, and food captivated our attention and imagination. As a boy in the early 1970s I can remember visiting Sukiyaki House, a Japanese restaurant in the city of Melbourne where most of the waitresses were Japanese war brides and having one of them write my surname in Japanese. It may have been the first Japanese restaurant in Melbourne and it was certainly my first experience meeting Japanese people and partaking of its food. It was in many respects the start of a life long association with the country of my great grandfather.

As for me, eventually I went and lived in Japan, first in the early 1980s as a student and in more recent years as a businessman. In short my heritage has become my life. In reflection, I can see that the 2nd and 3rd generations of the Hasegawa family had to deal with complex issues relating to race and hate, particularly during the war and its aftermath that saw them shun their Japanese heritage. It has been much easier for me.

© 2019 Andrew Hasegawa