Decision to go to Japan

Near the end of the war, the Canadian government gave the Japanese Canadians the unpleasant choice between dispersing east of British Columbia or being permanently “repatriated” to Japan. Sunao had no hesitancy in his decision as he had been planning to go back to Japan even before the war. He had been sending funds to Japan and had his older brother there purchase paddy fields for him. He also had ample savings (enough to build three houses, he would say), so was unworried and even optimistic about their future in Japan.

Eldest son Tadasu, embittered towards Canada by his experience of being incarcerated in the POW camp, was also strongly determined to go to Japan. Yasue, on the other hand, while also indignant about the treatment the family had received in Canada, was hesitant to leave. She had been warned about the harsh conditions in postwar Japan by friends who urged her to move with them to Toronto instead, but in the end decided to comply with the wishes of her husband and eldest son (whom she had not seen for four years and was missing deeply) in order to keep the family together.

Ship voyage back to Japan, Uraga Repatriation Center

On June 16, 1946, after a year of living in the Bay Farm internment camp where they had moved to wait for their “repatriation” to Japan, the Eto family boarded the General MC Meigs at Vancouver Harbor and began the voyage to Japan. At the time, Mary was 20, Betty 17, Margaret 14, John 12, Akemi 7, and Naomi just 19 months old. They had been eager to meet up on the ship with their eldest son and brother, Tadasu, whom they had not seen for the last four years, as he had been incarcerated in the POW camp since he was 19 years of age. Margaret explains, “For Yasue, being reunited with her eldest son was no doubt an unforgettable moment, but she later told us that Naosuke had seemed indifferent to her and she was not able to get much out of him.

Margaret vaguely recalls being very seasick during the whole trip. She says:

I personally have very little recollection of the voyage as I was sea-sick the minute we boarded the ship. I did not get up until I heard someone shout “There’s Mount Fuji!” I looked up at the distant horizon but we could not see Mount Fuji until someone said “Look up, w-a-a-y up!” and high above the horizon, we were able to get the imposing sight and majesty of the Mount Fuji we had seen so often in pictures.

Akemi, on the other hand, was hardly sick at all though she recalls the rough seas and sleeping in bunk beds. She has particularly vivid memories of how the passengers were behaving just after they arrived and disembarked at Yokosuka.

I was close to my mom because I was only seven years old. When we were getting off the boat, there were so many people running around, and they were taking the sink plug chains off the sinks and stealing them. Some of the people were taking pillowcases and hiding sugar in them…I was seeing so many things that were happening, everybody was going crazy…Before getting off the boat, I almost got lost. Everybody was rushing to the top deck—I didn’t know what was going on.

After getting off the boat, she noticed some Japanese people standing behind a fence nearby begging for food. She explains, “Some people were waving for handouts. At that time, I didn’t know what they were doing. I thought they were just waving to welcome us. Some of the passengers who had disembarked were throwing food to them and they were grabbing it.”

After landing at Yokosuka they were quickly transferred to the Uraga Repatriation center where they were given various inoculations. The quality of the food was very poor. Margaret remembers being given extremely hard biscuits which she and Sadao spat out. “All I remember is the hard biscuits we got in Uraga…They were so tasteless… and just hard!”

Train Trip to Kumamoto

Soon they were put on a train to Kumamoto. Margaret explains, “The long train trip to Kumamoto was filled with apprehension and dread as we did not know what to expect. When we saw the destitution, despair, and frailty of the people, I’m sure our parents were regretting returning to Japan, thinking ‘What have we got ourselves into?’” Elsewhere she eleborates in more detail:

At Hiroshima, hordes of wraith-like people tried to board the train—scarred, hairless, skeleton-like figures which was a disquieting moment for us. At other stations, beggars would swarm the train looking for a handout. As the train travelled along the bleak countryside, we noticed clothes hanging on trees and realized people were living in the caves nearby. This was post-war Japan and we were seeing the grim reality and despair in the lives of the people. (Nikkei Images p. 15)

Akemi remembers the train going through numerous tunnels and black sooty smoke entering the passenger cars. “There were lots of tunnels. You couldn’t even open the window because in those days lots of smoke came into the train with those coal-burning engines and all the faces would get black.”

She also recalls that it was on the train that she first met her eldest brother Tadasu. She had seen him on the boat and her mother had called out to him but he was busy helping the crew so briefly looked at them but didn’t reply. “In the train, that was the first time I met my big brother. When I woke up, someone was holding me, and I felt so strange because my mother was sitting there, but I was sitting on somebody else’s lap, and that was my big brother who I hadn’t met for 4 years!”

Trek to Iwasaka from Kumamoto City

After finally disembarking at Ozu Station at Kumamoto city, the family had to walk to their village, Iwasaka, about four miles away. Margaret explains,

The long trek to Iwasaka from Kumamoto city was a harrowing experience as we had to walk in the hot sun dragging our baggage. We children were in awe at the people we encountered on the way as they appeared to be like savages to us by the way they were dressed (or undressed as the case may be).1 Halfway there, a gracious grey-haired lady ran up to our mother and identified herself as our mother’s aunt whom our mother hadn’t seen since childhood. She offered us some watermelon and a shady rest which invigorated us for the rest of the walk.

Cold Reception from Relatives

Much to their surprise, when they finally arrived at the home of Sunao’s elder brother2 in Iwasaka, they were given an unusually cold reception. Margaret recalls:

When we arrived at the home of father’s brother, we sensed the hostility as his first words were “Why did you come back?” instead of a warm greeting. It did not help that we children rushed onto the tatami with our shoes on, eager to relax. (Nikkei Images p. 16).

When the elder brother threw Sunao’s bank book on the tatami mat, Sunao was devastated to notice that the balance would barely buy a sack of rice at black market prices.

Life in Postwar Japanese Village

Due to the postwar influx into Japan of repatriates from various former colonies and other countries, there was an extreme lack of food and accommodation in the villages. Hence, the Eto family of nine had to crowd into a zashiki (tatami mat room) in the home of Sunao’s elder brother for the first several months. Margaret recalls:

Once we had reached our uncle’s house and met with a cold reception, we settled into the zashiki (tatami room) which was made available to us. Every day we had all our meals on a straw mat in the yard with the matriarch (grandmother) doling out the miso soup to all of us. The men would be served first and we women were lucky to have whatever was left in the miso soup.

After several months of negotiation, Sunao was able to get back from his brother some of the rice fields he had originally paid for with his savings while working in Canada. Meanwhile, the family had moved to the brother’s tobacco drying house, a cramped, dimly lit one-room building (about 12 tatami) to which a lean-to shack was added to be used as a kitchen.

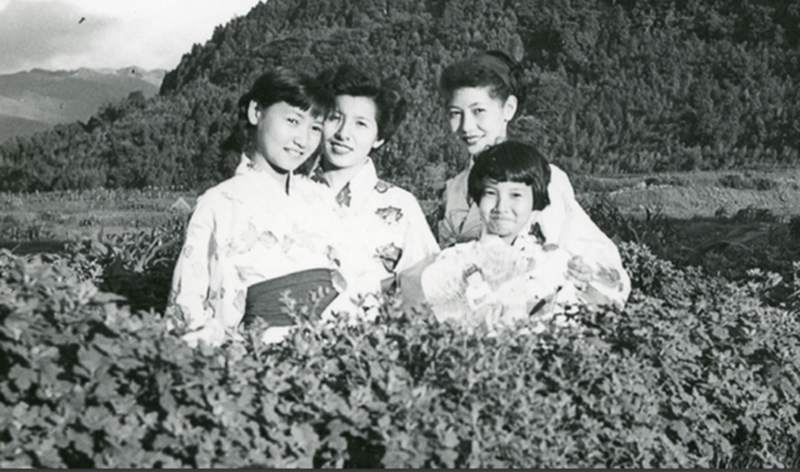

Sunao and Yasue worked hard raising rice and vegetables to provide sustenance for the family, but food continued to be scarce. The two eldest siblings, Tadasu and Betty, moved to Kumamoto city where they found employment, Tadasu as an interpreter/translator for American Occupation Forces, and Betty as an interpreter and desk clerk for a hotel catering to Americans. They were able to send some much-needed money back to the remaining seven members of family.

However, people in the village were hesitant to sell food to Yasue for money, so she struggled to purchase enough food for the family. Of Yasue’s persistent efforts to take care of her family, Margaret recalls:

“Throughout all of this, our mother did not waver in her determination to serve her husband and the youngest, Naomi, nothing but white rice while the rest of the family ate barley, buckwheat, millet, sweet potato, etc., and in retrospect, these were healthy substitutes. In spite of the rigorous conditions, the family did not catch any colds or serious illnesses.” (Nikkei Images, p. 16)

During this time, daughter Mary had begun to put to good economic use the sewing skills she had learned in the internment camp by converting old Japanese military coats and kimonos to western style clothing, which had become much in demand.3 Once word of her sewing skills got around, this became a profitable business.

Furthermore, Yasue had cleverly decided, instead of being paid with money, to have these customers to pay in food staples, thus resolving much of the family’s food purchasing problem. Later, Sunao was able to buy back more of his fields and provide more food for the family, and Mary and Margaret also found employment with the Occupation Forces in Kumamoto. During this time, the remaining family members moved out of the tobacco drying house into another tatami room for a couple more years while Yasue and Sunao continued to save money to buy a house and buy back land. Margaret recalls,

When the tobacco house became unavailable, we had to find another accommodation, but rental homes were almost impossible to find in the village. This resulted in renting another zashiki room for a couple years until our house was built. Yasue and I (Margaret) would alternately get up at four a.m. to start the fire to cook the rice in the makeshift kitchen for Sadao’s bento as he had to leave for school in time to catch the earliest train for Kumamoto city.

Finally, after some difficult negotiations with relatives, they bought a lot from Sunao’s elder brother in return for a rice field and built a house. Margaret explains:

There were ongoing talks to negotiate the return of the rice paddies to our father, and our mother enlisted the help of her father to resolve this, our mother being at the center of these talks. Our mother was the chief negotiator in most of these matters and she was responsible for getting the house built (with financial help from the income earned by Tadasu, Mary, and Betty) with her usual flourish, complete with ceremonies when the foundation was laid and the roof was raised.

Notes:

1. Elsewhere Margaret writes, “The family of nine started the trek in the hot sun, not aware of the strange looks we were getting. Instead, we children were shocked to see men clad only in loin cloths and old ladies carrying babies on their backs while wearing only a koshimaki. We thought we were back in primitive times in the wild jungles of Borneo.” (Nikkei Images, p 16)

2. Although their mother was still living, their father had already passed away, leaving the elder brother in charge of the family property.

3. Margaret points out that Yasue had wisely ordered a lot of fabric from Simpsons Sears before going back to Japan, “so we had all this fabric that my sisters could sew western clothes, and a lot of people brought in their yukata to be made into western clothes. Men would also bring their military coats to be converted into western style overcoats. Mother had also shipped (to Japan) her Singer sewing machine.”

© 2024 Stan Kirk