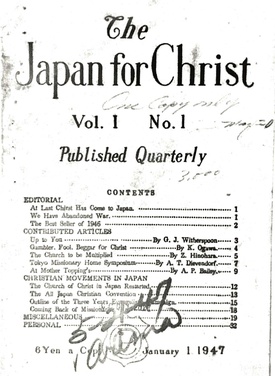

Some time ago, we did a column for Discover Nikkei on the Japanese evangelist and social reformer Toyohiko Kagawa. During his lifetime, Kagawa was renowned as a prolific writer—he authored some 150 books—and apostle of Christian socialism. Because of the spiritual dimension he brought to his leadership of movements for social and economic justice in the pre-World War II period, his American missionary associates often referred to him as the “Gandhi of Japan”—though when Kagawa actually met Mahatma Gandhi in India in 1939, the two clashed over Kagawa’s reluctance to publicly criticize Japanese imperial policies in Asia.

Our first column focused on Kagawa’s 1935-36 tour of the United States, during which he was initially denied entry because of his trachoma (which caused his partial blindness), and especially the connections he made with Japanese American communities during his stay. Following his return to Japan, Kagawa continued his writing and advocacy of social reform and international peace. Most notably, in 1940, during the Japanese occupation of China, he was briefly imprisoned by the military police for reprinting a public apology for Japanese aggression that he had made to Chinese Christians six years previously.

In 1941, he conducted a shorter speaking tour of the United States as part of a Japanese Christian Peace Delegation (Nichibei Kirisutokyō heiwa shisetsudan), in hopes of averting war between the two nations—which already seemed likely. The mission’s failure was underlined by Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor just six months after its close.

During World War II, Kagawa remained in Japan. His opposition to war was well known. However, with his activities closely watched by the Japanese government, he remained largely silent. In the latter stages of the war, Kagawa was pressured to demonstrate his patriotism. He agreed to record English-language broadcasts beamed at the U.S. in which he attacked America’s war against Japan as “savagery comparable to the lowest cannibalism,” and argued that if Americans had not lost the spirit of Washington and Lincoln, their leaders should cease their cruel perfidy.

In the aftermath of the war, even as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) undertook the occupation of Japan, Kagawa returned to his evangelization work and social welfare activities. He was appointed as one of the cabinet advisers to Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni, Japan’s first postwar prime minister, and received a seat in the House of Peers.

SCAP officials initially expressed suspicion towards him. Nevertheless, because of Kagawa’s status a potential leader for the Christianizing of Japan—which American authorities, notwithstanding their official support for freedom of religion, saw as desirable—as well as his expressed approval of General Douglas MacArthur’s rule, Kagawa was not purged by the Americans.

During this time, Kagawa retained a high level of celebrity among his American followers (“Japan’s No. 1. Christian,” TIME magazine dubbed him in 1946). American Protestant organizations were eager to invite Kagawa back to the United States. Their initial efforts were unsuccessful, however, due to SCAP’s strict regulation of overseas travel by Japanese personnel.

For example, the American Bible Society petitioned SCAP to grant permission for Kagawa to attend the group’s annual meeting in New York in May 1948. Officially, SCAP denied the request on logistical grounds, but internal memos show that they were equally concerned by the risk of negative publicity due to his controversial wartime record, stating, “SCAP could be open to criticism from various sources for either approving or disapproving the travel of Kagawa.”

A year later, an invitation from the Movement for World Evangelization—a London-based missionary organization led by Thomas Cochrane (1866-1953), a Scottish medical missionary who had worked in China prior to the war—finally presented Kagawa the opportunity to make his first postwar journey abroad. Following successful negotiations with SCAP, Cochrane obtained the necessary travel permits for the Japanese leader.

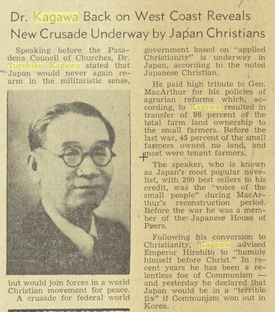

Kagawa departed for London in late 1949 on a six-month itinerary in the United Kingdom and Europe, during which he also stopped in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Kagawa’s followers then were able to arrange for him a five-month tour of the United States and Canada—once Kagawa was outside of Japan, SCAP bore no responsibility for his subsequent itinerary.

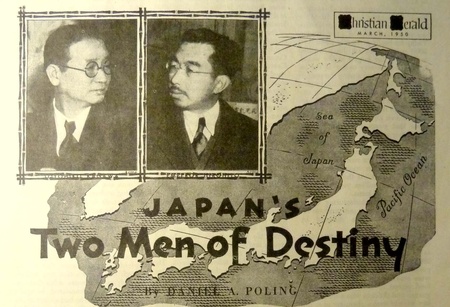

In the course of Kagawa’s first postwar tour, his American followers placed greater emphasis than previously on his Japanese nationality. In anticipation of Kagawa’s arrival, the Christian Herald—one of the most widely circulated Protestant news and general interest magazines at the time—published an article by its editor Daniel A. Poling titled, “Japan’s Two Men of Destiny.”

The piece, which opened with a photo of Kagawa next to that of Emperor Hirohito in a seeming nod to their physical similarities, went on to enumerate two common features in their outlook: “First, their passionate purpose to advance the peace and to make Japan the peace leader of the Orient just as she was its imperialistic master; and, second, their determination to defeat Communism and to establish a democratic order in the Far East.”

Kagawa’s American supporters also sought to capitalize on his informal alliance with General MacArthur. Prior to Kagawa’s arrival, Lumen Shafer—a member of the four-man deputation of American church leaders who had visited war-torn Japan in 1945—sent a telegram to MacArthur expressing his “earnest desire to quote you favoring Dr. Kagawa’s work and approving his visit.” While it is unclear whether MacArthur ever responded to this request, the press nevertheless played up Kagawa’s association with the general to help generate publicity and preserve his reputation from the taint of his wartime speeches.

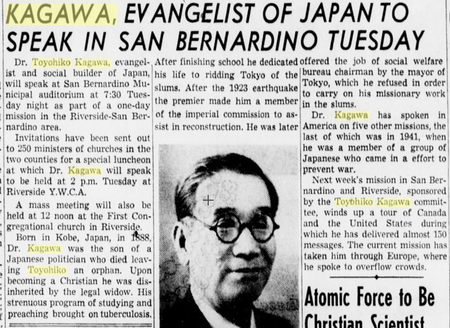

Kagawa arrived in the United States in July 1950. Highlights of his five-month trip included the acceptance of an honorary degree from Keuka College, a liberal arts college for women in upstate New York, and an address to a group of more than 700 missionaries and clergymen in Chicago—where Kagawa revealed his intention to request 10 million copies of the bible from U.S. religious organizations in support of the Christian movement in Japan. He also made an extensive tour of California, speaking in cities such as Pasadena, Whittier, and San Bernardino.

During his tour, Kagawa called on his audiences to apply the spirit of Christ to save the world in the Atomic Age, and to institute federal world government. Kagawa expressed support for the American-led defense of Korea, declaring that Japan “would be in a terrible fix” if Communism won out in that country. No doubt conscious of the feelings of his audiences, he was careful not to criticize the Americans for the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Nevertheless, he insisted that the atomic bomb had not brought about the surrender of Japan, which was already on the point of defeat, and opposed the use of the atomic bomb in Korea. At the same time, he praised MacArthur’s domestic policies in Japan, especially his agrarian reform program, and called for further aid to fight poverty in his home country.

The Japanese American press reported extensively and positively on Kagawa’s tour. Rafu Shimpō, for example, described the Japanese evangelist in glowing terms as “MacArthur’s Messiah.” Many Nisei attended his lectures in cities such as Chicago and Salt Lake City. In July 1950, Kagawa made a four-day tour of Southern California, during which he concentrated his efforts on interacting with Nisei audiences. The tour climaxed with an all-day series of meetings with Nisei ministers at the Mount Hollywood Congregational Church, followed by a public lecture.

According to Rafu, Mount Hollywood’s pastor Allan Hunter, who had been a staunch supporter of Japanese Americans during their wartime confinement, not only received Kagawa as a guest of honor at his church, but invited the Japanese evangelist to his private residence.

Kagawa’s speech at Mount Hollywood, in which he spoke of ending world hunger as a step toward international peace, was reported in the press and noted approvingly by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in her daily syndicated column “My Day.” Kagawa closed his tour of the American mainland in December in San Francisco, then made a five-day stop in Hawaii, during which he again connected in particular with the Nikkei.

In addition to speaking at such venues as the Nuʻuanu YMCA in Honolulu, he addressed a mass meeting at the Central Union Church with a speech in Japanese. He would return to the United States in 1953, when he spent one week in Hawaii and the mainland en route to a longer tour of Brazil. In 1954, he returned to the U.S. one last time as he made a three-month tour of the country surrounding his attendance at the second assembly of the World Council of Churches held in Evanston, Illinois.

He died in April 1960. Following his death, a group of Nisei churches in Los Angeles organized a collective memorial at the Union Church.

In the aftermath of Kagawa’s 1950 tour, Charles W. Hall published an article in the Christian Advocate, describing Kagawa as “the model of all that Christianity should mean”—an article that was thereafter reprinted in the popular magazine Reader’s Digest. Such testimony underlined not only the success of Kagawa’s tour and the popularity of his Christian message, but the extent to which he, not unlike Japan itself, had put his previous wartime notoriety behind him and been welcomed as a Cold War American ally.

For Japanese Americans in particular, Kagawa was a potent model and symbol. During his 1935-36 visit, he had boasted the allure of a rare Japanese celebrity on the international stage—Nisei were instructed firmly not to ask him for his autograph as it would cause too much commotion.

In contrast, during his 1950 tour, Kagawa stood as a representative of the Japanese people. For many Issei and Nisei, he was the first visitor from Japan that they had encountered since the war, and was a witness to their suffering during and after it. The Nikkei community’s welcome and affection toward Kagawa underlined the continuing connections they felt to their ancestral homeland.

© 2023 Bo Tao, Greg Robinson