Floyd Cheung, my brilliant friend and sometime collaborator, is a devoted scholar of Asian American literature. I was intrigued recently when I came across his essay on the poet, art critic and onetime “King of Bohemia” Sadakichi Hartmann—a piece written in conjunction with the release of a volume of Hartmann’s poems edited by Floyd.

In his essay, Floyd refers to Hartmann as a “missing link”: a groundbreaking modernist who helped bring Japanese poetic forms into English and to inspire poets such as Ezra Pound to take an interest. Yet Floyd notes that Hartmann was unjustly excluded from the Asian American canon, and cites the editors’ forward to the foundational 1974 anthology Aiiieeeee!, which dismissed Hartmann as inauthentic:

“The tradition of Japanese American verse as being quaint and foreign in English, established by Yone Noguchi and Sadakichi Hartman [sic], momentarily influenced American writing with the quaintness of the Orient but said nothing about Asian America, because, in fact, these writers weren’t Asian Americans but Americanized Asians.”

More recent critics as David Hsin-Fu Wand and Juliana Chang have acknowledged Hartmann as an Asian American writer.

I believe that to properly appreciate Hartmann’s place in Asian American literature, it is important to explore his relations with Japanese American communities, and particularly the extensive contacts he maintained in his later years with members of the budding generation of Nisei writers on the Pacific Coast.

To give some background, Karl Sadakichi Hartmann was born in Dejima, Japan in 1867 (probably), of a German father and a Japanese mother. He was raised in Germany, arrived in the United States in 1882 and settled in Philadelphia. He soon became attached to the poet Walt Whitman, then in his last years, and visited him at his home in Camden, New Jersey.

Hartmann later produced a slim volume about their relationship, Conversations with Walt Whitman (1895). He went on to become acquainted with many leading figures of modernism, from Gertrude Stein to Ezra Pound to Amy Lowell.

Meanwhile, Hartmann undertook a career as an international journalist and art critic for such journals as the Weekly Review and the Boston Transcript. He also wrote for the German-language newspaper New Yorker Staats-Zeitung und Herold. He founded his own short-lived journal, The Art Critic, in 1893. His two-volume History of American Art (1901) became a standard textbook for art history classes.

In addition to reviewing painting and sculpture, Hartmann was a pioneering essayist on modern dance, and especially on photography. A protégé of Alfred Stieglitz, he became a frequent contributor to Stieglitz’s periodicals Camera Notes and Camera Work.

Hartmann also distinguished himself as a poet and playwright. In 1893, he produced a symbolist religious drama, Christ: A Dramatic Poem in Three Acts, the publication of which led to his spending a week in prison in Boston. He continued to write religious dramas, including Buddha; Confucius; Mohammed; and Moses, as well as a privately printed novel, The Last Thirty Days of Christ (1920).

He also worked as a painter and performer. As scholar Hsuan Hsu has discussed, the most notable (or notorious) of his productions was a 1902 vaudeville act, “A Trip to Japan in Sixteen Minutes,” styled as a “perfume concert.” Using a large electric fan to blow different perfumes to the audience, Hartmann attempted to evoke sensual impressions in his listeners through smell.

Hartmann’s health and fortunes declined in later years. Debilitated by asthma and alcoholism, he moved to Los Angeles in the 1920s, but was unable to find steady employment in the film industry. Instead he spent time with the famed actor John Barrymore, becoming a “court jester” of sorts for Barrymore and his circle.

Barrymore biographer Gene Fowler later penned a book, Minutes of the Last Meeting, which presented Sadakichi as a boastful charlatan who cadged money from wealthy friends. In fact, despite his weakened condition, Hartmann continued to write poetry and criticism, and worked for years on an essay collection, Esthetic Verities. He connected with younger writers, to whom he served as a model and mentor.

The Nisei press devoted coverage to Hartmann and his public appearances. In March 1930, Sadakichi presided at an event, “An Evening with L.A. Poets,” at Schindler’s bookstore. Hartmann read poetry, lectured on writing it, and reminisced about poets he had known. Young poets were invited to bring samples of their work, which Hartmann would read and spontaneously criticize.

Rafu Shimpo encouraged literary-minded readers to attend. Mary Oyama Mittwer later described Hartmann at the event as reading through the proffered poems, and peremptorily rejecting all but a few as worthless.

Two years later, Rafu announced a lecture by Hartmann on “modern music,” based on a text taken from a chapter of Esthetic Verities. The article affirmed, “The Japanese community is invited to hear this noted Japanese critic.” Meanwhile, Kashu Mainichi publicized two appearances by Hartmann, whom it described as the “stormy petrel of literature,” at the Hollywood Arts Center.

Rafu, in turn, announced another lecture by Hartmann, on his “New Theory of Esthetics,” to be presented at a Sunday afternoon event at the estate of Otto Mattisen. The article hinted at the charitable motivations of the organizers: “The gathering will be more of a benefit for Hartmann, when people can hear him speak, as well as enjoy music and impromptu entertainment.” (Kashu subsequently ran a long feature article on the event that was reprinted from the Los Angeles Times).

Soon after, Kashu informed readers of another benefit for Sadakichi, featuring the unveiling of his plaster portrait by a local sculptor. Kashu proclaimed that in addition, there would be entertainers from ten different national groups.

Even as the Nikkei press publicized Hartmann’s lectures, young littérateurs extolled the man himself. In mid-1932, on the 50th anniversary of his arrival in America, he was hailed in an article in Rafu. “Hartmann has accomplished much and is one of the most widely known art critics from the land of the Rising Sun.” The article, no doubt following the author, described Hartmann’s collection Esthetic Verities as “an inquiry into the deepest meaning of man’s ethnic expression from prehistoric time to the present age of radio, jazz, and modernism.”

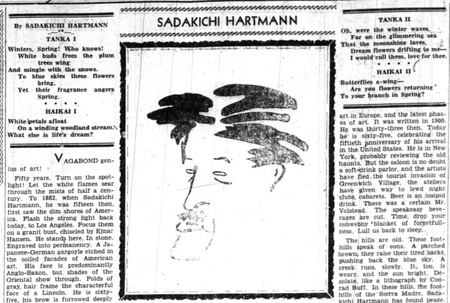

In November 1932, shortly after Kashu inaugurated a Sunday feature page, its budding editor Larry Tajiri (then just 18 years old) ran a set of tanka and haiku poems by Hartmann, including one called “Haiki 1”: White petals afloat/On a winding woodland stream./ What else is life’s dream? Underneath the poems, there was a caricature of Hartmann by artist Brownie Furutani. Tajiri included his own prose-poem tribute to “the vagabond genius of art,” in which he traced Hartmann’s career as artist, critic and friend of the great.

Tajiri praised in particular Hartmann’s coruscating irony, which made his work The Last Thirty Days of Christ, with its attempt to debunk the story of Jesus, “a brilliant book.” Tajiri concluded with his appreciation for Hartmann’s style. “Born in contrast, his life has been one. His elusive pen loves beauty. His tankas and haikais are essentially Japanese in tone and spirit as well as in rhythm.”

Within several months, Tajiri was singing a somewhat different tune. In a squib in his “Vagaries” column on the unveiling of the bust of Hartmann, Tajiri uncharitably called Hartmann, “a gargoyle on the facade of American arts and letters.” He repeated a comment from a high school girl who had met Hartmann in person and was taken aback by his grotesque appearance: “Why, he makes Frankenstein look like a pansy!”

In November 1933, Rafu Shimpo published a comic essay written by Hartmann, apparently commissioned by the journal. In it, he explained his confusion over the exact date of his birthday. “Most authors have a legitimate birthday which has its legal and social significance, an annual occurrence which they are proud to celebrate…I really do not know when I was born—‘a man without a birthday.”

The Nisei press did not stint on publicizing the bizarre side of Hartmann’s life, including a trial he underwent in 1933 on charges of stealing a taxicab—and his contention that his color-blindness was to blame! Articles also discussed Hartmann’s efforts to get his works published.

In 1934, Larry Tajiri noted in his “vagaries” column that Hartmann was on a trip to New York, seeking (vainly) a publisher for his book “Moses.” Two years later, an article in Rafu announced that Hartmann had completed Ethetic Vereties, but had abandoned attempts to publish it. Instead, he had given up his rights to the text and donated the manuscript to the Ridgeway Library in Philadelphia.

As the 1930s went on, Sadakichi Hartmann became increasingly reclusive and inactive. In 1938, then in his early seventies, he built a shack in Cahuilla, California, on land owned by local cattle rancher Walter Linton (whose 1933 wedding to Hartmann’s daughter Wistaria was extensively reported in the Nikkei press). In the shack, which he called “Catclaw Siding,” he intended to pass his retirement.

However, as the Pacific War dawned, Sadakichi faced government suspicion due to his Japanese ancestry, even though he had been a US citizen since 1894. While due to his age, poor health, and mixed ancestry, he was exempted from official confinement, he received regular visits from the FBI. He died in 1944, while visiting a daughter in Florida.

In his last years, Sadakichi was taken up by various members of the Nisei generation as an elder statesman. The most active was Mary Oyama Mittwer, head of the Nisei Writers and editor of its journal Leaves. Through a mutual friend, George Stanicci, she sought out Hartmann and befriended him. She used her influence to persuade Rafu to publish a set of four “Pastels in Prose” by Hartmann in 1938.

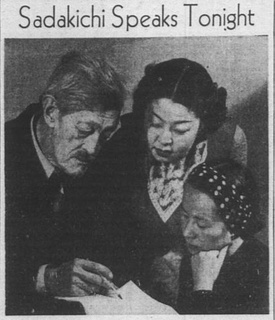

In early 1939, Mittwer championed the creation of a culture and education committee in the local JACL. The first event sponsored by the new committee was a lecture by Hartmann on modern art, held at the Nippon Club. Organizer Fumi Kuwahara warmly invited the community to come out in force: “this will be a rare opportunity for artists and culturally-minded nisei to hear Hartmann.” On the day of the reading, Kashu featured a photo of a fatherly Sadakichi with his adoring acolytes Oyama and Kuwahara.

Meanwhile, Mittwer produced twin essays on Hartmann for Kashu, which were then reprinted across the Nisei press. The first recapped Hartmann’s career as a critic and “legendary character”. Mittwer referred to Hartmann as “[O]ne who has lived life to the full and still found himself.”

The second referred to his work as author of “poems of rare beauty” (Mittwer recommended that all Nisei read his tanka and haiku), and spoke more broadly about his character and their acquaintance. She noted that upon first meeting “Sadakichi”, she expected to find him a forbidding and grotesque person, but described him as “a chuckling old soul full of pungent witticisms and dry humor.”

In September 1940, Hisaye Yamamoto mentioned Hartmann in the pages of her column “Napoleon’s Last Stand,” offering a plug for his new self-published book: “That ‘grand old man’ of art criticism, Sadakichi Hartmann, has authored Strands and Ravelings of the Art Fabric, a new book wherein he observes current art trends with no little scorn and offers some helpful suggestions. A copy of the work may be had by writing to him direct at P.O. Box 3030. Hollywood, California.”

Yamamoto’s column represented the last mention of Hartmann in the Nikkei press during his lifetime. His death in 1944 was marked in the Poston Chronicle and the Rockii Shimpo. In 1947, Larry Tajiri would write a more substantial appreciation in Pacific Citizen, where he lamented that Hartmann was all but forgotten to the public.

Nikkei press coverage of Sadakichi Hartmann’s activities testified to his contacts with artistic-minded members of Japanese communities, and their awareness of his work. Whatever his eccentricities, he was a forerunner who left a powerful legacy for Japanese American art and literature, one that is still being rediscovered by later generations.

© 2023 Greg Robinson