In the first half of this segment, I traced the career of Hollywood silent film actor Sojin Kamiyama. In the second half, I would like to flesh out aspects of the intriguing (and largely unknown) careers of Sojin’s wife Uraji Yamakawa and their son Edo Heihachi Mita [Kamiyama], who combined acting with work in other creative fields.

The woman who would gain fame as Uraji Yamakawa was born in Tokyo in 1885, the daughter of Morikazu and Komatsu Mita. Her birth name was Chie (Chiye). As a young woman, she trained at the Theater Institute. Upon her marriage to Tadashi Mita, she took the name Chie Mita. Their son Edo Heihachi Mita [Kamiyama], was born in 1908 (his obituary later noted his having three siblings in Japan, but this is unconfirmed).

According to legend, in their first years of marriage the young couple opened a shop specializing in eyebrow cosmetics on Hikagecho in Shiba, which Chie managed.

In 1910, as mentioned, the Kamiyamas helped establish the Modern Drama Society (AKA Modern Players Society), a theater group for producing contemporary drama. They took the stage names Sojin Kamiyama and Uraji Yamakawa.

In the group’s opening production, Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Uraji played Hedda. She won critical praise for her “mannerless manner” (in one critic’s terms) as the character. The play scored such a great success at the box office that its run was extended. (Uraji showed her versatility by singing a part soon after in a Japanese translation of Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute). The presence of women on the stage was still something of a novelty in Japan, where men traditionally played female parts, and Uraji became a celebrity on the national level.

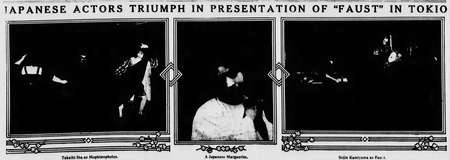

Her performances in Faust and other plays received international press coverage. This included a profile in the New York Times, which lauded her career as “a record of successes.” Following Uraji’s performance as Lady Macbeth in a production of Shakespeare’s play at Tokyo’s Imperial Theater in 1916, critic Eliose Roorbach commented, “Madame Uraji Yamakawa, as the queen, showed good dramatic power at times, but presented a most remarkably untraditional sleep-walking scene.”

In winter 1919, Sojin and Uraji left Japan, hoping to study Occidental drama in the United States and in Europe. After they arrived in Honolulu, Uraji was invited to lecture on the drama at the Nuuanu Y.M.C.A.

In June 1919, they starred together in a notable Japanese-language production of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. After three months in Hawaii, they sailed for the mainland. As mentioned, they were interested at first by the motion picture industry, but ultimately abandoned it and moved to Seattle.

Once in Seattle, the Kamiyamas were engaged to work for the Tacoma Jiho. By 1922, they were not only publishing their own newspaper, the Tozai Jiho, but also a journal, the Katei, for which Uraji did most of the writing.

According to Billboard magazine, both enrolled at University of Washington during this period to improve their English. In 1922, 14-year-old Heihachi, who had been left in Japan, sailed to America to join his parents.

In the early 1920s the family moved to Los Angeles, where Sojin achieved fame as a movie actor. Uraji left the stage. As a Los Angeles Times article put it, “She was the idol of the theatre-going public of Tokio. Then suddenly she gave up all this fame and glory and became overnight a modest retiring figure with old reminiscences of the plaudits of the crowds.” Picture-Play Magazine added: “[S]ince coming to America, [she] has been content to be merely an onlooker while her husband went along with his career.”

There is little information available on Uraji’s life during this period. She accompanied her husband to premieres and attended luncheons.

In 1927, Uraji briefly returned to acting, in the silent film The Devil Dancer. According to studio publicity, she accompanied her husband to the set of the film, in which he was cast. There she was spotted by the film’s director, who needed to fill a part. When asked if his wife could do it, Sojin allegedly smiled and said, “She acts a little.” Uraji played a Tibetan serving woman who risks death and torture to reunite her mistress with her lover.

Her performance drew admiring attention from cast and crew. The Los Angeles Times stated that once the film was shown, “those who know predict a great future for her in character roles.” However, Uraji seems not to have taken other roles during this period.

At the end of 1929, Sojin Kamiyama left California and settled in Japan. Apart from two brief visits, he never returned to the United States. Uraji stayed back with Heihachi in Los Angeles. While the Kamiyamas remained married, their union was clearly finished. Their split may have been accentuated by political differences, as Uraji became engaged in progressive causes. Communist activist Karl Yoneda stated that Uraji joined the L.A. Japanese branch of International Labor Defense in 1929, and helped found the Japanese Proletarian Artists’ League.

Once single, Uraji moved in several new directions. In 1930, she was featured (as Ura Mita) in a supporting role in the film Wu Li Chang. The production was a curiosity: a Spanish-language Hollywood film with mostly Latino actors, based on a British play about China previously adapted as a Lon Chaney silent.

While the film did not receive positive notices, the New Mexico newspaper El Nuevo Mexico praised Uraji’s work: “The role of the Chinese servant is played by Madame Sojin, wife of the well known Japanese actor Sojin, who speaks Spanish perfectly.” It would be Uraji’s sole credited film appearance, though she would play bits in the films War Correspondent (1932), Shanghai Express (1932), Clear All Wires (1933), and Navy Wife (1935).

In 1936, she directed the Kibei Shimin amateur theater group in a drama, “Eiji Koroshi,” performed at the Nishi Hongwanji Temple, then introduced a radio broadcast of the play on station KRRD.

Uraji meanwhile returned to journalism. In 1932, she was hired by Kyutaro Abiko, editor of San Francisco’s Nichi Bei Shimbun, to run the paper’s Los Angeles bureau. Although Kyutaro’s wife Yonako would take over the editorship four years later, upon her husband’s death, during that period there were few women occupying visible positions in the ethnic Japanese press.

Uraji would offer valuable assistance in turn to another woman, the Japanese immigrant feminist and peace activist Ayako Ishigaki (AKA Haru Matsui). In 1937, Ishigaki moved to Los Angeles and sought to write for local newspapers, both to support herself and help organize local communities.

She noted in a later memoir: “I first went to see Uraji, the wife of the actor…Kamiyama. I had heard of her even before I left New York from someone who knew her in the West Coast. When I asked Uraji to help me, she immediately introduced me to Mr. Suzuki, the chief editor of Rafu Shimpo, a Japanese newspaper. I went to see him and asked if I could be a freelance writer. He immediately accepted.”

Ishigaki would write for Rafu for several months and gain widespread attention for her columns, published under the pseudonym May Tanaka, before leaving the West Coast in the wake of Japan’s invasion of China.

In order to ensure a regular income, Uraji went into the cosmetics field. In 1931, she led a two-week class for Japanese women on the art of make-up, charging $5.00 to cover the cost of cosmetics and other incidentals. “Most of our Japanese women have no definite idea as to the proper application of cosmetics. Just daubing the face with expensive toilette is not make-up," she told a Shin Sekai reporter.

She thereafter founded the Uraji Cosmetics Company, and went on the road, selling cosmetics in cities such as Fresno, Dinuba, and Sanger. She lectured in local churches and YMCAs on cosmetics. She also visited girl’s clubs such as the Tartanettes and the Hiroshima Junior Society to offer tips on proper application of makeup. Drawing on her theater experience, Uraji worked as makeup consultant for community theater productions.

During these years, Uraji lived with her son Edo Heihachi Kamiyama. After studying art at the Otis Art Institute, Edo spent some time in France. Upon his return, he decided to undertake a movie career, following in the footsteps of his famous father, under the name Eddie Sojin.

In mid-1936 columnist Larry Tajiri reported in the Nichi Bei that Edo was one of a number of Nikkei appearing in the Bing Crosby film Anything Goes: “Many Japanese, including [Darrell] Meya, Teru Shimada and Eddie Sajin worked for hours in a studio-made rain.” Edo appeared that same year in Klondike Annie and in The Case of the Velvet Claws.

In 1937 mother and son joined forces to put on a play, “Nippon chiyuku fune” with a Southern California YBA unit. Heihachi wrote the script, adapting it from the radio drama “Jonan.” Uraji served as director. Each also worked on a film, Trade Winds (1938). Uraji played a bit as a nightclub patron, while Heihachi recruited Nisei to perform a Japanese dance in one scene.

Meanwhile, Heihachi shined as a proletarian poet. In fall 1936, he published Ashi-ato (Footprints), a volume of poetry. According to historian Masumi Izumi, he was an active member of the poetry society Hokubei Shin Kyokei. He also contributed to Kashi Mainichi and to Leaves, the magazine of the Nisei Writers. He also worked with the Nisei Young Democrats.

Through these circles,Heihachi met Nisei poet Chiye Mori. The two married in 1938 (Doho editor Shuji Fujii was their witness). Heihachi may have taken Mori into the family business, as she worked selling cosmetics. A census report dated April 1940 lists the three as living together. Chie is identified as a self-employed cosmetics saleslady, Heihachi as an actor at a movie studio, and Chiye as a costume researcher for a private individual. The marriage of Edo and Chiye did not last long.

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor and Executive Order 9066, the family was divided. Suffering from tuberculosis, Heihachi was confined in a sanitarium during the wartime period. Chiye threw herself into writing and political activism. In March 1942, she filed for divorce. Soon after, she was sent to Manzanar, where she was named editor of the newspaper Manazanar Free Press. By 1943, she had remarried.

Chie was not sent to an Assembly Center, which suggests that she was initially granted an exemption—perhaps to stay with her son during his time at the asylum. However, in early 1943 Chie was confined at Gila River (despite her cosmetics business, her admission form listed her primary occupation as “actress,” and her secondary profession as “Production of Chemical Products.”) Little is known of her later activities, except that she relocated to California after leaving camp in August 1945, and died there in November 1947.

In the postwar years, Heihachi worked as a magazine editor and actor under the name Edo Mita, and pursued his art. He was featured in such productions as the films Tokyo After Dark and The Crimson Kimono, an installment of the anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and in several episodes of the tv series Hawaiian Eye.

His most extensive media coverage was for his role in a semi-documentary film on Korean missions, “The Gathering Storm.” During this period, he was forced to defend himself, with the aid of the LA Committee for Protection of Foreign Born, against deportation from the United States due to his political affiliations. After a long process of appeals, he finally won the right to stay in court in 1959. He died of stomach cancer in 1963. A set of his papers is housed in the Japanese American National Museum.

Much of Uraji Yamakawa’s life remains uncovered, at least in English-language sources. However, she stands as a symbol of the extraordinary abilities that Issei women brought with them to America, and the difficulties they had pursuing independent lives. Her son Edo Mita, meanwhile, exemplifies the West Coast literary and artistic circles that were destroyed by mass incarceration.

© 2023 Greg Robinson