Lillian Michiko Yano, Newmarket, ON

I know who I am because of 123 Wynford Drive… so long ago…48 years ago, in 1975.

In 1952, my family came to Toronto after their forced removal to excruciating lives in Alberta sugar beet fields. My father had decided that the best way for our future was to assimilate into mainstream Canadian culture. But secretly, like all Japanese Canadians seeking a new beginning in Ontario, he was proud to be Japanese.

Perhaps this is the reason why the first Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre at 123 Wynford Drive meant so much to the Issei and Nisei who sacrificed their meagre savings to hang on to their identity as Japanese living in a Canada which had betrayed them.

My parents worked seven days a week and never enjoyed the centre themselves. Yet 123 Wynford Dr. embodied their legacy rising from the ashes of their broken lives, a memorial of hope for future generations.

In 1950s Toronto, my sister and I were the only Japanese Canadian children around for miles. We were encouraged to think white outside the home and Japanese in the home. We worked harder than everyone else to be model citizens in a white society. I denied being Japanese. In later years I explored all things Japanese, but I was always an outsider looking in – never as one who belonged.

That is the price that Sansei paid to be Canadian.

After completing a Fine Art degree, I was at loose ends, with no confidence to exhibit my art. One day, my lifelong friend and fellow artist Mary Akemi Morris invited me to exhibit work in ARTISAN ’75 at 123 Wynford Drive.

123 Wynford Drive inspired pride in me, partly because of its understated beauty and elegance, and partly because it was designed by one of the sons of the Japanese Canadian community who had “made it” in a field dominated by white architects. It was one of the earliest works of Raymond Moriyama, who has since become one of Canada’s foremost architects.

The building and its surrounding gardens were a true reflection of the serene, low-lying structures of Japan, and every feature invited self-reflection. Moriyama had envisioned a building that was in harmony with nature in the abundant use of beautifully crafted wood and stone surfaces throughout the inner and outer spaces.

Behind the building was a lovely garden that inspired contemplation and inner harmony. In front of the main entrance was an incredible cantilevered sculpture with a spiral of layered slabs of natural stone, landing as if flung by the hand of God Himself. It stood before me with mute pride.

Perhaps it was the aesthetic beauty of the place that inspired me to agree to take part in the annual arts and craft show. At the time, I felt torn. My feelings were mixed. I was proud to be Japanese, yet acutely aware that I was not one of “them”. I had become white. I was a closet racist.

Today, when I look back at myself, I am horrified. I created soft sculptures as if I were possessed by a demon. In one month, I designed and sewed eighty pieces, each one unique, each one a work of art. A few days before the show, I suddenly thought I would like to create a real art piece, an appliquéd wall hanging, which would form an eye-catching backdrop to my display of soft sculptures. At that time, I had no idea that this wall hanging would change my life.

As I was sitting by my display, a chic woman in an immaculate cream-coloured suit, dark glasses, and a hat which was tilted precisely at the right angle to give an air of mystery, approached me. I could not see her eyes behind the dark glasses. She glanced at the work and surreptitiously handed me her card. I looked at it:

Evans Gallery

123 Scollard Street, Toronto

Ruth Levinson, Director

The only words she spoke were, “Why don’t you bring me some of your other work. I’m looking for a fabric artist.” This was the beginning of my life as a professional artist.

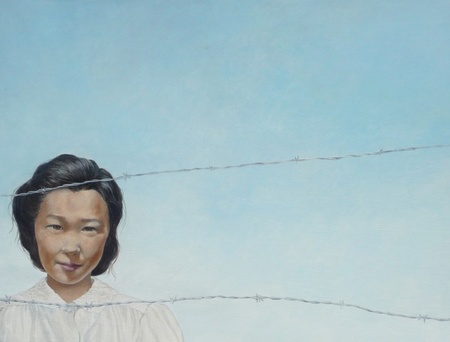

In my first solo exhibition I created my most important work, the lone creation which delved into my dark Japanese world. MIRROR was an analogy of my two selves. I explored my dilemma of being two people in one – being Canadian and being Japanese.

I wrote: “Mirror” is an introspective piece which attempts to express my ambiguous feelings resulting from belonging to two very different cultures. It is a highly symbolic work. The two women are really one, as if one of them is looking at a mirror image of herself. Both are Asian. One is in a Western dress and the other is in a Japanese kimono. But who is the real person and who is the image in the mirror?

One day, Sol Litman, Canadian journalist and community human rights activist who wrote editorials for the Toronto Star walked into the gallery and we began a conversation about MIRROR which has remained with me all these years. Just the two of us. He made me understand the importance of searching for my identity through art which reflected the pain of a people who had lost everything.

Decades passed after that conversation before I found the courage to tell my family story through my art. Sadly, my parents passed away before they saw my work. My crowning achievement was to have my work included in the 2019 exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum’s ON BEING JAPANESE CANADIAN: reflections on a broken world, curated by Bryce Kanbara and Katherine Yamashita. My portrait of my mom, “Reiko, Alberta 1945” became the iconic image of the exhibition.

123 Wynford Drive gave me my first step to discover who I am as a Canadian who is also Japanese. If 123 Wynford Drive is erased from the Japanese Canadian story, I also, would feel erased.

Les Takahashi, Toronto

My earliest involvement as a volunteer at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (JCCC) at 123 Wynford Drive was during my young adult years, the 1970s, when the JCCC was part of the Metro Toronto International Caravan, also known as Caravan. The promotion of Japanese culture through the Caravan was an emotional boost.

Also, during the 70s my wife and I joined the Sunday Niters Social Ballroom dance club. It was weekly ballroom dance lessons attended by Nisei, my parents’ generation. We became an integral part of the JC community. Both my Caravan and Sunday Niters experiences took place in the auditorium of the JCCC. Through these activities, I built what had been a missing connection with the Toronto JC community.

In contrast, during the 1950s and 60s, my childhood neighbourhood was WASPish central Etobicoke. In school, through almost all grades, there were few JC students. I could count on one hand the number of JCs in my schools. There were few JC families in our neighbourhood and we, the children, did not associate with each other. So, other than my family and relatives, there was no JC community in my childhood.

Much of the time I acted like I was a member of that WASP community. But there were occasional pointed reminders that I was not seen by many as part of that community. At worst, there was open racist hostility. I developed a sense of identity hollowness. I didn’t truly belong among my childhood classmates or neighbourhood playmates, and I didn’t have a JC community to support me.

I know my parents experienced adult forms of being outsiders, but during those Sunday Niter dance classes and the parties and dances associated with the dance club, they could be themselves. Without reservation at the JCCC, my parents were in their community. This was a healing experience. After the abuses they experienced in British Columbia in the first half of the 20th Century, this was a way to begin the healing of those wounds.

Although racism did not disappear, the JCCC was a sanctuary for us. The Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre was for me a community in physical form. It was at 123 Wynford Drive, that Japanese Canadians who gathered there accepted me unreservedly into this cultural community, my community. The physical altering or destruction of the building at 123 Wynford Drive hurts my heart. I know I am not alone, not in the JC community, not in the Toronto community.

Elm Tahara, Toronto

I used to compete in their annual judo tournaments. It was our club vs. the Centre's club. I can't remember if others were invited. The last one I went to (1970/71) was where I fractured my elbow! But it was all friendly competition.

I also went to their bazaar as a kid. I remember all the food and merchandise at the tables. My mother used to cook and work at the bazaar and at the city's annual Caravan event. Every summer all the different ethnic groups would showcase their cultures at venues in Toronto. Here is a picture of her cooking for Caravan at the Centre.

© 2023 Norm Ibuki