PERSPECTIVES ON NISEI IN THE UNITED STATES

I would like to introduce interesting articles about how Nisei in the U.S. were viewed by Japanese in Japan and the American public as well as how Nisei in the U.S. viewed Japan.

1. A Viewpoint of a Japanese Female Student on Nisei in the United States

“Her View on Nisei – Perception of Japanese Living in the United States to Their Homeland is From Meiji and Taisho Eras” (October 4, 1935 issue)

Miss Mineko Tsukimoto, who visited the United States as a student representative for the Japan–America Student Conference held in Portland this summer, gave her impressions of the Nisei living in the United States. She says as following:

“Nisei girls in America all look like American women. However, I was impressed by their surprisingly good Japanese. I think this is the result of the sudden rise in the number of people using the Japanese language after the Manchurian Incident, and the fact that various aspects of Japan have been studied. Recently, Japanese traditional dance is very popular in the United States. Also, tea ceremony and flower arrangement are both very popular, too. Many of them, however, think about Japan in the Meiji and Taisho eras, which they only heard about from their parents, and it seems that they still think that way today. I think they still don't understand enough.

“Also, it seems that Nisei girls don’t like gentlemen who were educated in Japan. And they want to go and see Japan, but they don’t think it’s a place to live for a long time. I think it’s probably the same as we could enjoy learning in the United States for a few years while we were young, but we feel that it’s not a place to live for a long time. It is understandable if a foreigner feels that way, but it is strange to me that it is the idea of people who are inheriting Japanese blood.

“. . .Nisei boys, like American boys, are quiet, docile, and feminine. It seems American men like Japanese women. And Nisei boys say they want to find a good job in Japan and return home. This is probably because they are treated equal to white people at school, but when they try to find a job, it is very hard to get a good position. Therefore, many of them regret that they no longer possess Japanese nationality.”

2. A Viewpoint of Nisei Male in the US on Japan

“A Nisei Talks about Japan” (November 1, 1936 issue)

He said as follows: “If you come to Japan, you must have some interest in researching Japan. When you come to Japan with the idea of American superiority, you may have some trouble.”

He continues: “You believe in American superiority and look down on Japan; you should not come to Japan. If you come to Japan, you need to understand Japan and you should be willing to behave as Japanese do in Japan. Otherwise, you may easily notice the materialistic disadvantages in Japan compared to America.. However, those aren’t disadvantages because Japan is a spiritual country. If you visit Japan without understanding that part, you have never understood Japan.”

He also wrote of his ideas on Nisei marriages. “If you come to Japan and find your spouse in Japan, you may be satisfied with your partner, but you don’t have any confidence to have a successful family relationship with your in-laws in Japan. If you want to create a truly happy family, you should get married to an American who understands American values.”

3. A viewpoint of the American Public on Nisei in the U.S.

“Anti-Japanese Newspaper Praises Nisei Japanese Americans – The Oath to be Loyal to the United States” (May 1, 1939 issue)

In the May 4th issue of Ken Magazine, which publishes profane comics and anti-Japanese articles, an article by Ernest Painter praised Nisei with a picture as follows:

“The heart of the Issei is in Japan and they are eager to go back, but the emotional state of the Nisei and Sansei is completely different. American-born Japanese citizens have the best grades in public schools. Even their bodies are different because of nutrition and exercise. Those Japanese Americans are the most diligent and hard-working.

“. . . When it comes to the question of whether Japanese Americans should be loyal to Japan or the United States, they tend to be loyal to the United States. In the case of a US–Japan war, for example, if they were persecuted just because they are Japanese, they may lose their loyalty to the U.S.; while if treated properly, Nikkei citizens as well as first-generation Issei must be as loyal to America as, if not more than, other races.”

This article predicts a war between the United States and Japan and provides a keen insight into the loyalty of Issei and Nisei to the United States. I feel that this article reflects his deep understanding of the Nikkei feeling at that time.

Nisei Marriage Issues

The issue of Nisei marriage became the most serious issue in the Japanese American community, and many meetings were held mainly by the Japanese Association to discuss how to resolve this issue.

“Marriage Roundtable” and “Sad Community Story of Marriageable-Age Girls Who Missed Opportunities” (December 8 and 12, 1934 issues)

On December 7, Chuzaburo Ito, Yoshitaro Fujihira, Shojuku Amano, Shinsaku Sawada, Sokichi Hoshide, Tadashi Yamaguchi, and others attended a roundtable discussion on the issue of Nisei marriage, hosted by the Social Affairs Department of the Japan Chamber of Commerce (Nissho).

. . . When Mr. Fujihira, as the chairman, gathered statistics of the birth rate in the Japanese community through a survey at the time of the extension of the Japanese school, it showed the number of births reached a peak between 1919 and 1920. Since then, it has been gradually declining, but those who were born at that time have already reached the age of 16 or 17, and they are now majorities [of youth]. In other words, many women will reach marriageable age soon. . . . I heard that there are about 100 women at the age of 22 or 23 in the Seattle and Tacoma areas. About a year ago, there was a meetup for marriageable-age youth in California and about 30 men joined an event, but there were no female participants despite the inviting females as well. Although most of the male participants are Kibei, many women considered American-born men as undesirable spouses because they were too “Yankee” to marry. Also, they thought those men tended to want a girl who could accept all of their demands.

In modern society, people consider the ideal marriage age for females as between 22 and 23; and for males it is 30 years old. Considering this as the norm, the numbers of marriage-age males and females in our community look good if people of the same age get married, but there are considerable problems with girls born in the transition period [1919-1920]. This is where our social difficulty arises.

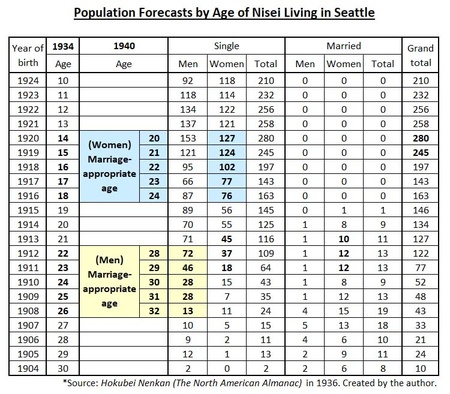

Hokubei Nenkan (The North American Almanac) in 1936 lists the population of Seattle by age. This data is presumed to be the actual results in 1934 and is almost matched with the data from the above article.

If we estimate the number of marriageable-age youth—females aged 20 to 24 and males aged 28 to 32—in 1940, we can see that women overwhelmingly outnumbered men. (Table 2)

NISEI WOMEN’S MARRIAGE IN JAPAN

Sumiyoshi Arima, in the column “Hokubei Shunju,” said the following about Nisei women’s marriages:

“Nisei women’s marriage in Japan” (January 20, 1939 issue)

There is an opinion that sending Nisei to Japan is one way to solve the marriage problem of Nisei women. This isn’t a good idea and in fact, it’s not really feasible. Marriage in Japan isn’t as easy as in the United States. In Japan, there is an age limit for women to get married; they consider women aged 23–24 are too old to marry. Therefore, it would be much harder for a Nisei who is almost 30 years old to find a suitable spouse in Japan. Even if she can find a partner, it might be a remarriage for him.

. . . After all, Nisei women, for better or worse, are American girls; psychological, educational, and conventional differences with boys from Japan never bring happiness to either of them.

. . .In terms of life, I think the United States is probably the happiest place for Nisei women. However, the difficulty in marrying older girls is a real problem. It cannot be solved no matter how they think about it unless they find partners by themselves. If we left this issue unsolved, there could be a huge risk for us to face various social problems. Therefore, I think it would be wise for Nisei women themselves to be aware of their own status and circumstances, and for their parents to face reality and compromise where appropriate. A woman, after all, finds her happiness in marriage.”

MARRIAGE BETWEEN NISEI

The North American Times frequently published stories of engagements between Nisei men and women and their weddings from 1938 to 1942. Here, I would like to introduce an article about the marriage between Nisei in the midst of tension during the war in 1942.

The January 21, 1942 issue shared a story of the engagement between Nisei in Seattle with the names of the bride and groom as well as of the matchmakers to celebrate their marriage. It mentioned that the groom happily enlisted in the United States Army.

The January 27th issue of the same year featured the engagements of two Nisei couples in Seattle, and the February 5th issue featured a marriage of one Nisei couple.

Furthermore, the issue of February 16th just before the order of Japanese American incarceration ran a story of Fumiko, the third daughter of Chiyokichi Natsuhara, who was the owner of Auburn Natsuhara Company and was considered an influential senior leader. She exchanged betrothal gifts with Joji, the eldest son of Yasukichi Iwasaki who was a wealthy farmer living in Hillsboro, Oregon; and their wedding was to be held at the Oregon Buddhist Church in the near future.

Looking at these articles, I feel that Nisei marriages during the war gave them strong confidence and pride as Japanese Americans to survive in the United States.

Although many Nisei were caught between Japan and the United States and suffered from the issues of dual nationality and marriage, they faced a tremendous challenge with the earnest support of the Issei and their own efforts. They contributed to the development of Japanese American society in the future.

In the next chapter, I would like to introduce articles about the universities in which Nisei enrolled.

Reference:

Hokubei Nenkan (The North American Almanac), Hokubei Jijisha, 1928 and 1936.

Edited by The Committee of Japanese in America for Preserving Historical Events, Zaibei Nihonjin Shi (History of Japanese in America), Zaibei Nihonjin-kai, 1940.

Mitsuhiro Sakaguchi, Nihonjin amerika iminshi (The History of Japanese Immigrants in America), Fuji shuppan, 2001.

*The English version of this series is a collaboration between Discover Nikkei and The North American Post, Seattle’s bilingual community newspaper. The first part of the article was originally publishd on May 28, 2023 in The North American Post and is modified for Discover Nikkei.

© 2023 Ikuo Shinmasu