In recent years, Chin Music Press has produced a great run of graphic novels on the wartime Japanese American experience. These include Frank Abe and Tamiko Nimura’s collaboration with illustrators Matt Sasaki and Ross Ishikawa on We Hereby Refuse, and the partnership of Kiku Hughes and Ken Mochizuki on Those Who Helped Us.

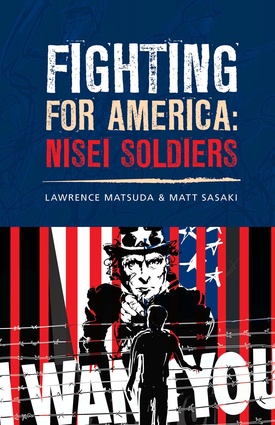

Now Sasaki has “returned,” this time working with educator and activist Lawrence Matsuda on a revised version of their graphic book Fighting for America. As with We Hereby Refuse, Sasaki brings his artful eye to depicting the biographies of several Nisei soldiers and their diverse experiences in the Atlantic and Pacific theaters during World War II. Matsuda’s skillful storytelling, based on interviews with several of the soldiers profiled, makes Fighting for America a visually gripping read and ideal for young adult audiences.

The origins of this project go back to 2013, when Paul Murakami suggested that Matsuda produce a graphic novel that would help preserve the stories of the Nisei veterans. Knowing that visual storytelling works well with younger audiences, Matsuda collaborated with Matt Sasaki on giving life to these stories.

With support from the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle, Matsuda and Sasaki produced an initial version of Fighting For America in 2015. Several of the stories were then adapted into television shorts for the Seattle Channel series Community Stories, with the segment on Shiro Kashino winning a regional Emmy award. However, due to a cutoff of grant funding, the series eventually ceased publication. Now, in its new format, Fighting For America will re-appear as a part of Chin Music Press’s series on the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans.

For his graphic novel, Matsuda and Sasaki selected six Nisei soldiers, all of whom hailed from the Pacific Northwest: Shiro Kashino, Frank Nishimura, Jimmie Kanaya, Roy Matsumoto, Tosh Yasutaka, and Turk Suzuki. Each biography offers a twenty-page glimpse into the war stories of these soldiers and their personal struggles with their service.

Matsuda also shares a particular connection with his subject: as a former Army medic, Matsuda adds a personal insight into the war experience that is normally absent from works on nisei soldiers. Combined with Sasaki’s eye for evoking emotions in his portrayal of scenes, these vignettes offer readers a moving depiction of the sacrifices each of these soldiers made to serve their country and survive the war.

Each story shines in a certain way. Seattle-born Shiro Kashino enlisted from Minidoka concentration camp into the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. In one dramatic scene, Kashino accuses the colonel of the regiment of deliberately sending them on suicide missions in Italy, leaving many of his comrades dead. Later, Kashino is forced to spend six months in an Army stockade, after breaking up a racially motivated fight between a white soldier and a fellow Japanese American.

Frank Nishimura of Seattle remembers vividly the support he received from Miss Mahon, the principle at Bailey Gatzert High School, at a time early in the war, when many other Seattleites shunned Japanese Americans like him. It was Mahon’s words that carried Nishimura through his combat experiences in Italy and France, during which he went through several near-death experiences.

For Jimmie Kanaya of Clackamas, Oregon, the war triggered several traumatic events. Here, Matsuda and Sasaki excel at illustrating the horrors that Army medics endure in saving their comrades on the battlefield, as well as the uncertain likelihood of survival for casualties.

Kanaya also endured additional suffering when the Germans captured him in Vosges Mountains in France, while he was helping rescue the Lost Texas Battalion. Kanaya spent the last part of the war in a prisoner of war camp in Poland. The added irony of this, of course, is that Kanaya’s own family was incarcerated at Minidoka at the same time. Kanaya endures several months of brutal hardships, ranging from malnutrition to confinement in poorly-constructed barracks at sub-zero temperatures. At one point, German guards force Kanaya and his comrades to march 400 miles from Poland to Hammelburg, Germany to flee the advancing Soviet forces.

Shifting to the Pacific Theater, the book tells the story of Roy Matsumoto. A translator embedded with the famed Army special operations unit Merrill’s Marauders, Matsumoto played a crucial role in helping the unit navigate the jungles of Burma and decipher Japanese messages. On several occasions, Matsumoto spied on Japanese units to pinpoint their movements and ambush them. In one startling scene, Matsumoto instructs his comrades to destroy his dog tags if ever he is killed, so that his family in Hiroshima will not be detained by the Japanese police. Matsumoto’s translation work saves the lives of his comrades on several occasions and blocks the advance of Japanese forces in Burma.

In the last two biographies, readers get an overview of life in the Minidoka camp and the emotional struggles of enlisting out of camp. In the case of William “Tosh” Yasutake, enlisting in the 442nd represents an opportunity to escape camp. After toiling in the sugar beet fields of Idaho and facing limited opportunities in camp, Yasutake decides to enlist in the Army. The choice is not easy, for Yasutake’s father is interned by the FBI in another camp, leaving his mother and siblings (including his sister Mitsuye, the future poet and author Mitsuye Yamada). After a trip to Lordsburg Internment Camp, Yasutake receives the blessing of his father to enlist.

Here, Sasaki’s images and Matsuda’s narrative capture several difficult moments common to families in camp. Yasutake’s story also includes the added nuance of depicting the divide between Hawaiian Japanese soldiers and those who came out of camp.

For Turk Suzuki, the journey from Seattle to Minidoka with his family, as described in the book, captures all the hallmarks of the incarceration experience: Turk’s Issei father is arrested by the FBI, the family endures austere conditions at Camp Harmony (one detail that stands out is of Turk’s sister being separated from her family and quarantined in a horse stall after contracting measles), the trains with the windows covered, and the divisive moment of responding to the loyalty questionnaire.

One minor point that would have improved the arc of each story would have been for the authors to have added further details regarding the postwar journeys of each soldier. While this is true in some cases, such as the story of Shiro Kashino, other narratives abruptly end with the soldier’s return back home. Brief descriptions of their struggles to adjust to postwar life would have further underlined the sacrifices that these remarkable individuals made for their country, despite the racial prejudice and harsh conditions they faced.

As part of the expanding literature on the combat experiences of Japanese American soldiers, Fighting for America offers a unique regional contribution to the topic, heightened by the stunning visuals drawn by Sasaki. Readers from the Pacific Northwest, especially those in middle school and high school, will particularly appreciate Matsuda and Sasaki’s graphic work.

© 2023 Jonathan van Harmelen