During World War II, Japanese communities around the Pacific rim and elsewhere were subjected to displacement, internment, or incarceration. While the case of the West Coast of the United States is the most well-known, several nations hastily developed their own incarceration policies based on the assumption that Japanese communities, regardless of citizenship status or loyalty to the country, supported Japan.

In most cases, the punitive treatment of Japanese immigrant communities followed in the trail of longstanding immigration policies to exclude and discriminate against Japanese communities. Perhaps no better example illustrates this than Australia’s treatment of its ethnic Japanese resident.

Outside of Australia, the incarceration of Japanese Australians received very little attention from journalists during the war years. However, in the postwar era, Nikkei journalists in the U.S. and Canada wrote several articles criticizing the Australian government for its continuing anti-Japanese discrimination.

In this article, I will examine how Nikkei journalists in the U.S. and Canada concerned with lingering anti-Japanese sentiment in North America covered Australia’s postwar anti-Japanese policies as a topic of discussion and a warning to their readers. To be sure, very few U.S. and Canadian papers paid close attention to Australian internment policy, or vice versa— the few mentions of the U.S. and Canadian incarceration policies are the subject of a separate paper.

Perhaps no country in the Pacific world successfully prevented the immigration of Japanese nationals like Australia. Since the turn of the 20th century, Australia mandated a “white Australia” policy that prevented the immigration of people from Asia to the continent and any chances of naturalization. Several laws, such as the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, curtailed the migration of Japanese nationals to Australia. Despite these draconian policies, some did migrate.

On the eve of the Pacific War, around 1,200 Japanese nationals and their children called Australia home. Among this population, only those 16 and older were required to register as noncitizen aliens.

Immediately following Pearl Harbor, the Australian government, citing the National Security Act of 1939, rounded up its population of the 1,141 Japanese Australians and confined them to camps guarded by the Australian Army. An additional 3,160 individuals of Japanese ancestry from the Dutch East Indies, New Zealand, and New Caledonia were sent to Australia for detention there, with the French government cruelly shipping the Japanese community of New Caledonia to Australia in cages.

For the duration of the war, Australia confined Japanese Australians in four camps across the interior: Loveday, Tatura, and Hay. Many of these camps also housed prisoners of war from Germany, Japan, and Italy, further underscoring to those confined that they were treated as enemy combatants. At the end of the war, the Australian government deported the majority of the confined Japanese Australians with some exceptions.

Historian Yuriko Nagata described Australia’s internment policy as having eliminated the majority of Australia’s Japanese community, leaving very little traces of what existed before the war. For the June 1947 census, only 335 individuals claimed Japanese ancestry.

Australia’s wartime incarceration policy fell in line with the greater White Australia policy of the 20th century. In some cases, Australia’s treatment of Japanese Australians garnered support from white supremacists overseas.

In Canada, journalists pointed to Australia as an example of the success of anti-Japanese immigration policies in preventing the need for internment. In the May 4, 1942 issue of The Vancouver Daily Province, journalist Paul Malone praised Australia’s White Australia policy as having helped preemptively avoid the need for an incarceration policy:

“Thanks to the White Australia policy, there are practically no Japanese in Australia. With their defensive and offensive strength gaining rapidly, Australians confidently say there won’t be any change in their Asiatic-barring policy except perhaps for Chinese allies.”

In other words, Malone argued Canada envied Australia’s racist immigration bans, as it saved Australia from the anguish of having to decide how to justify forcibly removing citizens.

Australia continued to exclude Japanese nationals until 1952, when the government began to gradually lift immigration bans to accommodate the war brides of Australian servicemen returning from Occupied Japan. However, Australia’s doors remained largely shut for a further generation.

The notorious history of anti-Asian discrimination that defined Australian in the late 19th and 20th centuries both served as a positive model of exclusion for West Coast racists, and a negative example of the triumph of racism in the eyes of Nikkei communities. Exclusionists in the United States and Canada modeled their “Gentleman’s Agreements” on the 1896 policy announced in Queensland, which unofficially instituted a policy blocking Japanese immigrants.

Although North American press coverage of Australia’s internment policy was limited, a select few commented on the topic to serve other purposes. As will be seen, the blatancy of Australian racism was not lost on Nikkei journalists in North America.

During World War II, Japanese American and Canadian community presses offered little coverage of the experiences of Japanese Australians. Often, Japanese American newspapers mentioned Australia in reference to Nisei interpreters who recounted their experiences while stationed in Australia in letters to the editor. Often, these letters centered on life in Australia, with most focusing on the weather in Australia, diseases such as malaria, or the importance of their contributions to the war effort.

For example, in the July 15, 1943 issue of the Gila News-Courier at Gila River Camp, Sergeant Masato Iwamoto of the Military Intelligence Service shared an account of life “Down Under,” notifying readers that Australia is “much like California,” and that “we are nearer to accomplishing our mission, we are more determined than ever to contribute our fullest knowledge and spirit to the war effort.”

In a letter from Sergeant Terry Takahashi reprinted in the Topaz Times from February 12, 1944, Takahashi told readers that he “heard a lot of stories that I had malaria over here (Australia) and was very sick. Well, that’s far from the truth.”

What is left out of these articles is the reason why Japanese American translators were stationed in Australia. Because the internment policy prevented most Japanese Australians from enlisting in the Armed Forces (with some exceptions), Nisei translators from the United States conducted the bulk of translation services for the Allied Forces in the Pacific. Around 30 Japanese Australians served in the Australian armed forces in the Pacific and European theaters, with some, like soldier Mario Takasuka, serving in both theaters.

In the postwar years, the Japanese Americans and Canadians community formally criticized the Australian government’s continuation of the White Australia policy. In several Japanese American community newspapers, journalists highlighted Australia’s discriminatory treatment of individuals of Japanese ancestry.

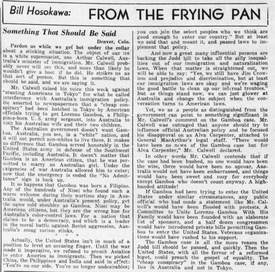

On May 29, 1949, Nisei journalist Bill Hosokawa penned a critical article about Australia’s Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell. In a pointed attack on Australian racism, Hosokawa described Calwell as a “white supremacist. Mr. Calwell probably never will see this, and more than likely he wouldn’t give a hoot if he did. But this is something that should be said, and we are saying it.”

The incident that sparked Hosokawa’s anger was a press conference held by Calwell in protest against U.S. officials pushing for Australia to allow Filipino American soldier, Lorenzo Gamboa, to visit his wife and two children in Melbourne. Although Gamboa was one of many U.S. soldiers stationed in Australia for translation work during the Pacific War, he soon found himself banned from the country following the end of the war due to his race.

Calwell singled out U.S. officials for interfering in Australian affairs, and claimed that permitting Gamboa to enter would set a precedent for other Asian refugees to enter the country and even promote miscegenation. Hosokawa noted to readers of the Pacific Citizen that the same ban would apply to the thousand of Nisei translators stationed in Australia despite their service in the Pacific War.

In addition to angering Asian American journalists like Hosokawa, the Gamboa incident incited outrage from major Pacific powers, including the U.S. While Hosokawa acknowledged the irony of the U.S., a Jim Crow nation at the time, for criticizing Australia’s White Australia Policy, he concluded that the U.S. could redeem itself by passing immigration reform.

In the months that followed, nisei journalists continued to refer to Australia as a white supremacist state. Often, the commentary on Australia centered on Immigration Minister Calwell’s doubling down on his anti-Japanese views.

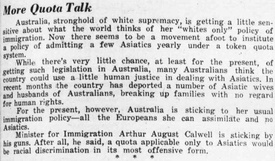

In July 1949, the Pacific Citizen highlighted the government’s decision to deport “a number of Asiatic wives and husbands of Australians, breaking up families with no regard for human rights.” In October 1949, the Rafu Shimpo reprinted Australian Immigration Minister Calwell’s statement that Japanese war brides and their children would be barred from entering the country. In another press release from Toronto, the Rafu Shimpo recorded the statement of Australian delegate P.J. Kennelly to the Commonwealth Conference of Labor Parties, where he declared that Australia “never will permit immigration of colored peoples.”

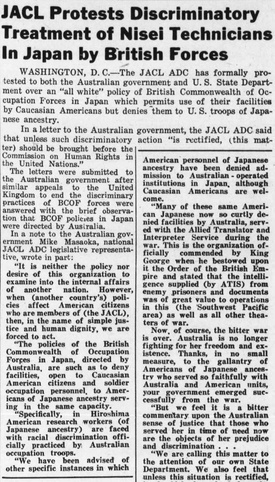

Australia’s discriminatory policies even affected Japanese Americans. On November 12, 1949, the Pacific Citizen announced that the JACL would protest the mistreatment of Nisei servicemen who have been refused service in Australian-run soldier’s facilities in Occupied Japan. In a letter written by Mike Masaoka, the JACL declared that “it is a bitter commentary upon the Australian sense of justice that those who served her in time of need now are the objects of her prejudice and discrimination.”

A week later, Pacific Citizen editor Larry Tajiri described this, and Australia’s refusal to allow athletes of Japanese ancestry from competing in the 1956 Olympic Games, as “adopting some of the most disturbing aspects of the [Nazi] government that once ruled Germany.”

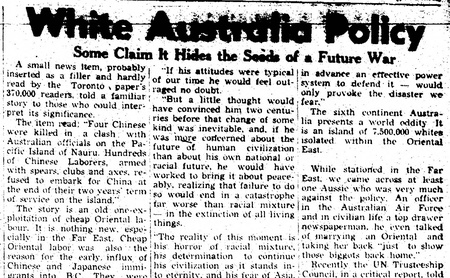

In Canada, Japanese Canadians similarly decried Australia’s discriminatory policy towards individuals of Japanese ancestry. On September 1, 1948, the Japanese Canadian newspaper The New Canadian published an eye-catching article titled “White Australia Policy: Some Claim It Hides the Seeds of a Future War.” The article declared that in the postwar world, the denial of human rights by countries like Australia is unacceptable, and even asserted that the countries of East Asia would be willing to go to war over such discrimination.

In a similar editorial in their July 20, 1949 issue, The New Canadian ran an editorial comparing South Africa and Australia’s racist policies, noting in particular that Australia continued to deny entry to any non-white migrants. The author concluded that racism, whether in Australia or South Africa, stood in the way of the fundamental aims of the United Nations of world harmony.

In other cases, the criticism of Australia focused on treatment of Nisei soldiers stationed in Japan. On November 23, 1949, The New Canadian published an article by Ken Adachi on the Japanese American Citizens League’s statement protesting the Australian government’s discriminatory treatment of Japanese American soldiers in Occupied Japan. Adachi wrote for the New Canadian a scathing critique of Immigration Minister Calwell’s statement that Japan would be barred from competing in the 1956 Olympic Games in Australia. Adachi used the statement to discuss the discrimination that Japanese American soldiers faced in Australian-run facilities:

“The Aussie government always seems to be breeding discrimination. In Japan, there’s the Aussie operated BCOF hotels which refuses to allow any person of Japanese ancestry in its portals. It doesn’t matter whether he is a Japanese of American ancestry who’s played his part in winning the war for the Allies. That’s a many treatment for any ex-GI.”

The criticism by Nisei journalists and others led US officials to pressure Australia to end discrimination – with some results. On October 20, 1951, The New Canadian reported that Japanese American Tommy Umeda was granted an entry permit after initially being refused entry when he told immigration officials about his combat service in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Yet the end of Australia’s discrimination towards Japanese immigrants would not end until 1952, when pressure from ex-soldiers to allow the entry of war brides led to an end of the policy.

On May 9, 1953, the New Canadian declared that “War Brides Help to Build Japan-Australia Amity,” and stated that many younger Australians will come of age without the prejudice of their parents. Yet despite this progress, the article noted that anti-Japanese prejudice leftover from the war remained “the greatest single obstacle to fully restore Australian-Japanese relations.”

In both the U.S. and Canada, Nikkei communities continued to readjust to their postwar lives. Although discrimination against Japanese communities in the U.S. and Canada persisted, Nikkei journalists saw Australia’s blatant racism as both a new threat to the global Nikkei community. It also served as a means of improving their own treatment at home by teaching Americans and Canadians alike to not emulate the Australian example.

* Special thanks to Elysha Rei and Andrew Hasegawa for their help with this article.

© 2023 Jonathan van Harmelen