Vindicating Camp Survivors

Tamaki felt that he and the rest of the legal team were on a mission to vindicate their families, that their suffering would be recognized. The legal team, including Tamaki, also wanted to weaken the precedent of the Korematsu decision as much as possible.

In the original 6–3 decision, the precedent was set that the military could deem any group potentially dangerous and round them all up. Men, women, children, the elderly, and anyone else would be herded and stripped of their rights; all of which could be done without evidence or a trial. In the decision, one of the dissenters, Justice Robert Jackson, wrote, “...it lies around like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority who can put forth the plausible claim of an urgent need.” Tamaki wanted to ensure that the same thing that happened to Japanese Americans couldn’t happen to any other group of Americans.

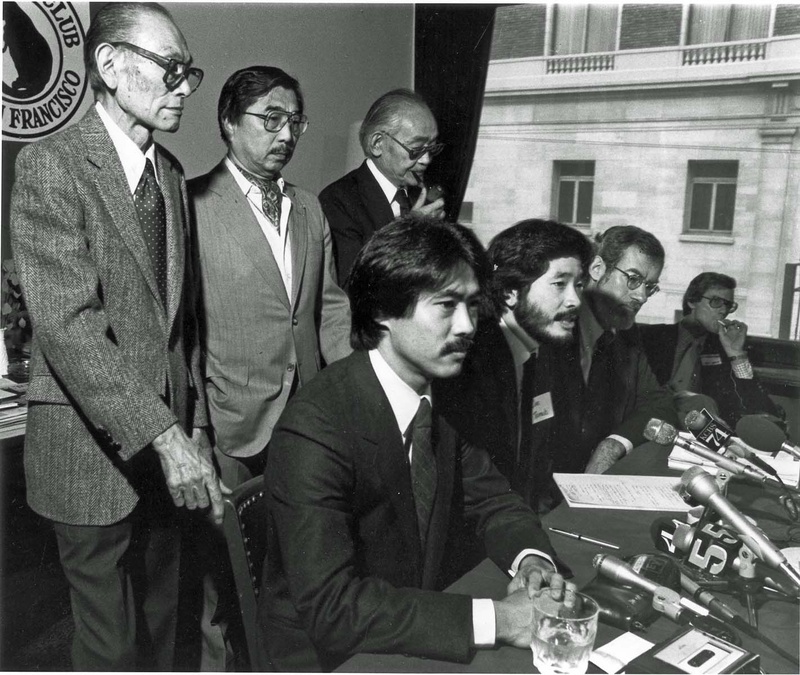

In 1983, before a San Francisco Federal Court room packed with camp survivors, Judge Marilyn Hall Patel ruled that the government’s claims that Japanese Americans were spying were falsehoods, and threw out Korematsu’s criminal conviction establishing that there was no good reason for the mass imprisonment, and that the government knew it at the time.

The overturning of Korematsu’s criminal conviction boosted the near 20-year redress and reparations movement of Japanese Americans. The effort for redress and reparations was very controversial, even within the Japanese American community. Some incarcerees didn’t want to relive the trauma from camp. However, the mindset of the general public and the Japanese American community changed over time. Tamaki and other activist groups worked to educate people about what happened in the camps and why it was important to every American.

Tamaki recounted one anecdote about the process, saying, “I was priming the press and calling them the day or two before saying, ‘You know, we’re going to do this.’ First of all, they said, ‘What are you talking about? Concentration camps? When did this happen?’ That was one question. Another one was, ‘Aren't these Japanese prisoners of war? Isn’t that what you’re referring to?’ I said, ‘No, these are American citizens.’”

Through the efforts of activists like Tamaki, the sentiment is very different today. Japanese American incarceration is taught in the California public school curriculum now. There are historic sites dedicated to educating the public, and even museums and monuments to make sure the history is never forgotten.

Fighting Systemic Racism Today

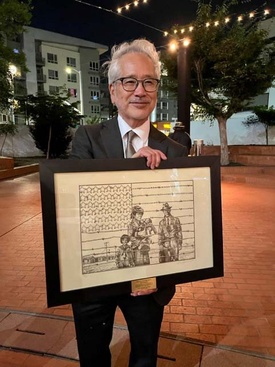

Tamaki’s experience and expertise on the subject of Japanese American incarceration and the redress and reparations process made him a prime candidate for the California Reparations Task Force. This commission was tasked by Assembly Bill 3121 to assess what the state could do to address its role in the enslavement and systematic oppression of African Americans. The task force held 27 days of hearings and processed hundreds of pages of documents, and produced a 1,100-page final report, including its recommendations to the Legislature for reparations.

Tamaki stands alone as the only non-African American serving on the task force. In his words, “Our charge was really threefold…to document the harm of 246 years of enslavement; 90 years or more of Jim Crow and racial exclusion and terror; and decade after decade after decade thereafter of racial discrimination right up into modern times.”

Even though California entered the Union as a free state in 1850, California embraced Jim Crow policies and enacted fugitive slave laws. This enabled African Americans to be chased down, arrested, and deported back to the South even though they had been living in the “free” state of California. California actively worked with private interests to prevent African Americans from accessing loans in a process called “redlining,” disallowing African Americans from buying homes as well as manipulating eminent domain projects to raze African American communities to make way for freeways, subways, public works, and other projects.

Tamaki cites, “Between 1949 and 1973, there were 2,532 eminent domain projects where cities could declare private property condemned because it was needed for public use. So those projects that were going on in 992 cities, 1 million people got displaced, two-thirds of whom were African American. And so, these are improvements that enhance the productivity and the wealth of an entire region, but African Americans disproportionately lost their homes and businesses as a result.” Currently, Tamaki and the California Reparations Task Force are working to address California’s role in systemic racism.

Allyship to Create Change

Tamaki’s experience with one of the few successful redress and reparations movements in modern United States history makes his perspective valuable to the movement for reparations for African Americans. As a Japanese American, Tamaki knows what it is like to be discriminated against based on your race. He, like many other Japanese Americans, knows the pain that xenophobic attitude and generational trauma can have.

According to Tamaki, the racial oppression experienced by the African American community is unparalleled, but we are able to empathize with them. He understands the reparations are more than just a check in the mail, but rather redressing a long and ongoing wrong. Reparations are a starting point to healing for the African American community. Tamaki views his role as an ally to their community.

In the movement to overturn Korematsu, there was tremendous allyship within the minority communities. Without allyship, no marginalized community will be able to create change on their own. Tamaki is serving as a liaison between the African American and Japanese American communities, using his own experience to draw support. When asked about his role within the task force, Tamaki said, “We have to get involved in moving the needle of public opinion, organizing to rally support, to educate the public about what it is. It’s more than a check in the mail.”

My conversation with Don was something that I will carry with me for the rest of my life. His determination to help his community and also succeed professionally is something I never thought was possible. His perspective made me passionate about issues I thought were unimportant to me. We, as a community, need to stand in solidarity in order to achieve great change. Tamaki is truly an inspirational figure. Throughout his life, he has worked tirelessly to fight for the civil rights of marginalized communities and continues to do so today. I hope to emulate his passion for what is right, and I call upon all of us to do the same.

* * * * *

The Japanese American Bar Association (JABA) Legacy Project creates profiles of prominent jurists, legal legends and leaders in the Japanese American community through written articles and oral histories. In particular, these profiles pay special attention to these pioneering jurists’ reflections on JABA, their distinguished careers, and their involvement in the Japanese American community.

This is one of the main projects completed by The Nikkei Community Internship (NCI) Program intern each summer, which the Japanese American Bar Association and the Japanese American National Museum have co-hosted.

Check out other JABA Legacy Project articles published by past NCI interns:

- Series: Pioneering Jurists in the Nikkei Community by Lawrence Lan (2012)

- Series: Legal Legends in the Nikkei Community by Sean Hamamoto (2013)

- Series: Two Generations of Pioneering Judges in the Nikkei Community by Sakura Kato (2014)

- “Judge Holly J. Fujie—An Inspirational Woman Who Was Herself Inspired by Japanese American History and Community” by Kayla Tanaka (2019)

- “Mia Yamamoto—A Leader Who Defined the Nikkei Community” by Matthew Saito (2020)

- “Patricia Kinaga—Attorney, Activist, and Mother Who Has Given a Voice to Those Who Don’t Have One” by Laura Kato (2021)

- “Justice Sabrina McKenna—The First Openly LGBTQ Asian American to Serve on a State Court of Last Resort” by Lana Kobayashi (2022)

© 2023 Drew Yamamura