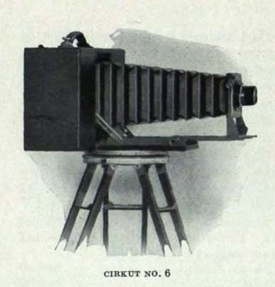

While Tei managed the farm, Wakaji pursued his gifts. He first studied photography through a correspondence course. According to family legend, he moved to San Diego for a period to study photography in more depth. He may have been a student of Masashi Shimotsusa, a photographer who studied in London and Paris before opening a studio in San Diego in 1919, and later a photography school.1 Wakaji may have learned how to make panoramas from Shimotsusa, who was accomplished in the technique (Fig. 3). Whatever his exact path may have been, by 1922, Wakaji was an active photographer in Los Angeles, and he was listed as such in the 1922 Japanese Who’s Who in America.2

Wakaji gained employment at the studio of Toyo Miyatake, the son of the first Japanese confectioner in Los Angeles. Like Wakaji, Miyatake did not want to follow in his father’s footsteps. He wanted to be an artist, and for practical reasons he decided to focus on photography. After taking a course with a local photographer, H. K. Shigeta, Miyatake bought the Paris Photo Studio in 1923 and renamed it the Toyo Studio.3 It was located on East First Street in the heart of Little Tokyo. Miyatake struggled to make a financial go of it before he was finally successful enough to add employees, including Wakaji.4 Eventually, the Toyo Miyatake Studio would become the best-known studio in Little Tokyo, to the point that almost every family in the Little Tokyo area at the time had portraits or wedding photographs made by Miyatake.

Wakaji may have been hired to make panoramic photographs, at which he was skilled, or he may have learned the technique at Miyatake’s studio. Either way, Wakaji produced a remarkable group of panoramas in 1926 and 1927, when he, of his own volition, systematically documented Los Angeles-area farms that were operated by Japanese Americans (Figs. 4, 5, and 6).

In these panoramas the families and their workers were often seen standing amid the fields, as if they themselves were rooted in the ground like the produce they cultivated. The images are wistful, poetic, and poignant. We see the humble homes and the crowed competition of the markets, but we also sense the dignity of these people, even if they are clothed in tattered overalls. These photographs graphically demonstrate both the difficult life of Japanese Americans, as well as their resolve and resilience.

In addition to documenting area farms, Wakaji also recorded his own life and farm, activities in Little Tokyo, the produce market, and his children’s schools (Figs. 7 and 8).

Most importantly, Wakaji also made art photographs—works created as personal expression without a practical purpose. He was a member of an art photography group, the Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California (JCPC), who were based in Little Tokyo. Photographs by members of this club were exhibited and published internationally to critical acclaim.

While Wakaji did not exhibit extensively, he did show in the club’s first exhibition, held in 1926. He presented six prints: California Field, Silent Under the Bridge, Road to Valley, Study, Parade, and In the Temple.5 Sadly, none of these prints are currently known to exist with the exception of In the Temple, which is the photograph taken within the Hompa Hongwanji Buddhist Temple when it was constructed in 1925 (Fig. 9).

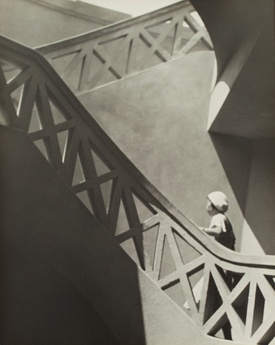

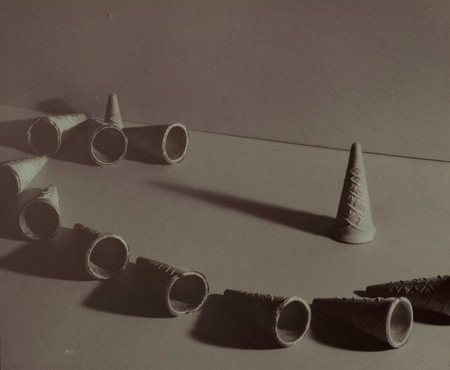

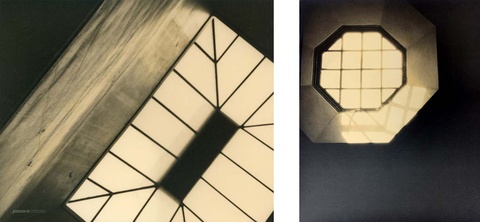

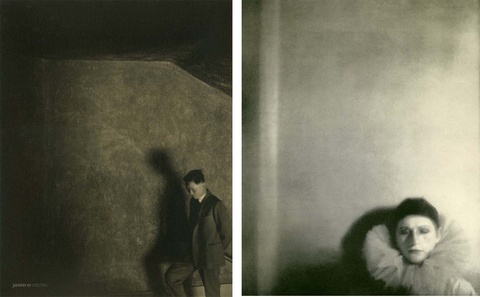

Wakaji’s membership in the JCPC put him at the center of an influential photographic community, one that in recent years has been recognized for its forward-looking modernism. Their photographs broke with conventional European depictions of deep space, emphasizing the flat, two-dimensional space found in Japanese art. These compositions include areas of voids, asymmetrical arrangements, shadow patterns, and bold geometric shapes. Their subjects were often arranged on flat surfaces, in front of a wall, or viewed from above by downward-pointed cameras, all of which furthered the flat, two-dimensional character in their photographs. Frequently, a single isolated figure, lost in a landscape or among geometric patterns, appears in their images.

The Japanese Americans derived this style from sources that were inescapable for them—their heritage of Japanese art and culture. The patterns and shapes found in textiles, the compositions of Ukiyo-e prints, the spatial divisions of Japanese architecture, the artful arrangements of ikebana, the graphic nature of calligraphy, the seeming simplicity of haiku poetry, were among their many influences.

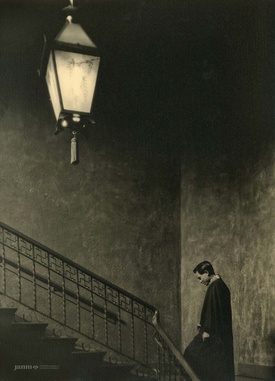

Wakaji’s art photographs reflect these same influences, and they are consistent in subject and style with prints made by other Japanese Americans. One photograph of a man in the temple mentioned earlier (Fig. 9), is similar to works by other JCPC members, such as the image of a single figure on a stairway in Hisao E. Kimura’s, To Roof Garden, (Fig. 10).

Shadow patterns play an important role in Wakaji’s Shadows on Wall, (Fig. 11), as they do in Shinsaku Izumi’s The Shadow, (Fig. 12).

The Japanese Americans were particularly admired for their modernist, often geometric compositions. T. Sata’s, Untitled (Ice Cream Cones) (Fig. 13) is a fine example, and so is Wakaji’s Untitled (Skylight Abstraction), (Fig. 14) and Untitled (Window Abstraction) (Fig. 15).

While Little Tokyo seemed to be an isolated, almost insular ethnic enclave, such was not the case. Area photographers established extensive connections throughout the US, Europe, and Japan. For example, the JCPC presented the first exhibition in the United States of prints by Shinzo Fukuhara, the father of Japanese art photography. Photographs by members of the JCPC were included in major exhibitions in London, Paris, and Tokyo, among many other cities, and their works were reproduced in publications that were distributed across the globe, giving them an international presence. Their visual style was admired by members of the European avant-garde, such as Moholy-Nagy, whose compositions often used the same visual effects.

The photographers in Little Tokyo were closely associated with famed photographer Edward Weston, who visited JCPC member’s studios, and with Margrethe Mather, who juried the first exhibition of art photography in Little Tokyo sponsored by The Rafu Shimpo in 1924. Weston and Mather were both interested in Japanese art, which influenced their work considerably. Their compositions frequently featured the same visual elements that were used by the Japanese Americans, such as large areas of voids, asymmetrical arrangements, shadow patterns, and compositional elements placed near the picture edge.

Another photograph by Wakaji of the Hompa Hongwanji Buddhist Temple reveals a close connection between his work and that of Mather. A man is seen walking up a stairwell, his head tilted down, a shadow cast behind him, with nothing else in the photograph but a wall and ceiling (Fig. 16). The image mirrors Mather’s photograph, taken around 1921, entitled Pierrot (Otto Mathieson) (Fig. 17). In both, a flat, “empty” area occupies most of the photograph, with a figure positioned in the lower right corner. At the time, such spare, asymmetrical compositions were atypical of images made by most photographers working in the United States.

Though his output was small, Wakaji’s art photographs demonstrate his contributions to the vital photography community in Little Tokyo during the early 1920s. Later in Japan, where he returned, his photographs reflected other influences and took on a greater significance due to a momentous historical event.

Returning Home—Hiroshima

Wakaji and Tei, who had eight children, weighed the challenges of continuing to farm in Southern California versus the advantages of returning to Japan. A loving note sent home from the teacher of their son, Noboru, suggests that the children enjoyed a good education in Los Angeles, which Wakaji and Tei valued—but it was not a Japanese education. The desire to see their children benefit from an education in Japan, coupled with two years of potato crop failure, encourage the family to return to the place of Wakaji’s birth, Hiroshima, in the summer of 1927.6

Hiroshima “was a fan-shaped city, lying mostly on the six islands formed by the seven estuarial rivers that branch out from the Ota River; its main commercial and residential districts, covering about four square miles in the center of the city, contained three quarters of the population,” as John Hersey described it in his poignant and disturbing post-atomic bomb essay of 1946, Hiroshima.7

The city was built around Hiroshima Castle, the construction of which began in 1589. At the time, shopkeepers and tradespeople were encouraged to establish a castle town in the manner of Kyoto and Osaka.8 Tideland reclamation projects south of the castle resulted in some thirty-five new villages that became a part of the city, and by the early 1800s, Hiroshima was the sixth largest city in Japan with a population of some 70,000 individuals. With the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894), the Hiroshima-Ujina rail line was constructed for military use, bringing additional economic growth to the area.

Further railroad development connected Hiroshima city to the port of Kure, an increasingly important shipping and shipbuilding harbor during the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War. By 1929, two years after Wakaji and his family had returned to Hiroshima, the city was bustling with 270,000 thousand people. It had become one of the educational, cultural, political, and economic centers of Japan.

Wakaji’s primary motivation in returning to Hiroshima was his desire to leave farming behind and make a living entirely from photography. Earlier in Los Angeles, even before Wakaji became an active photographer, there was an abundance of Japanese-run photography studios. By 1918, there were no fewer than twenty-seven photographers active in Little Tokyo, and the number was growing.9 For Wakaji, the competition would have been fierce, and it would have included his former employer, Toyo Miyatake.10 Hiroshima, on the other hand, with its continued economic expansion, offered Wakaji a better opportunity.

Upon his return to Hiroshima, Wakaji established the Hiroshima Shashinkan, or Hiroshima Photography Studio, in the Naka Ward, at the center of Hiroshima, less than 1,000 feet from the Aioi “T” Bridge that would later, in 1945, become the target of the first atomic bomb (Fig. 18). The location was at the very center of commerce in Hiroshima, and it was a perfect site for a photography studio.

Notes:

1. Letter to author from Jane Kenealy, Archivist, Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego, December 20, 2019, containing School of Photography, Notice of New School Opening, an advertisement translated into English and housed at the Society.

2. Japanese Who’s Who in America (Tokyo: Japanese American News, 1922), 359.

3. Miyatake studied with H. K. Shigeta, who had a studio in the Tomeo Hotel at the corner of 2nd Street and San Pedro Avenue where he gave lessons. It would have made sense for Wakaji to do the same, but to date there is no evidence that Wakaji studied with Shigeta, nor is there family lore to that affect.

4. Miyatake hired a number of area photographers in the mid-1920s. T. Kobari, M. Kokobun, and Kaye Shimojima, the leader of the JCPC, are listed at the Miyatake studio address in the 1927 American Annual of Photography, for example.

5. The JCPC was known as The Japanese Camera Club of Los Angeles during the time of its first salon, before adopting the name Japanese Camera Pictorialists of California the following year.

6. Email letter from Hitoshi Matsumoto to Karen Matsumoto, undated.

7. John Hersey, Hiroshima (Knopf: New York, 1946), 7.

8. “The History of Hiroshima City,” The City of Hiroshima (accessed 4/4/2022)

9. Note research by Tim Asamen and book by Eiji Furukawa.

10. Among the other studios was one run by Kinso Ninomiya, who was also born in Hiroshima, along with the K. Ito Studio, Izuo Studio, Komaki Studio, Tanaka Studio, Terachi Studio, and T. Utsushigawa Studio. Additionally, there were a number of suppliers of photographic materials, many on East First Street.

* * * * *

This essay was written in conjunction with the Japanese American National Museum’s online exhibition, Wakaji Matsumoto—An Artist in Two Worlds: Los Angeles and Hiroshima, 1917–1944, which highlights Wakaji’s rare photographs of the Japanese American community in Los Angeles prior to World War II and urban life in Hiroshima prior to the 1945 atomic bombing of the city, and artistic photographs of daily life in both cities that were created as a form of personal expression.

View the online exhibition at janm.org/wakaji-matsumoto.

*All photos by Wakaji Matsumoto (copyright Matsumoto Family)

© 2022 Dennis Reed