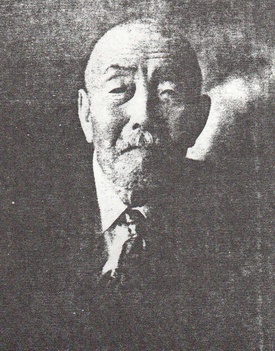

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in January 1942, the Canadian government announced that it would send Japanese men between the ages of 18 and 45 to the road camp. Iwaichi Kawashiri, the 44-year-old owner of the boarding house then, was the camp leader and elder. He was an intelligent and courageous man to be recognized. Mr. Kawashiri gathered over 30 men from Tottori prefecture, and a total of 108 Japanese men headed to the road camp on March 12, 1942.

“We were tricked into believing that the rest of the family did not have to relocate if the men joined the road camps.” The person who tricked us was Mr. Morii, a boss in Nikkei society at the time.

Mr. Kawashiri was a leader and peacemaker who oversaw the entire camp, and cared for all the Japanese in the camp. However, the men who joined the camp for the sake of Japanese society and to protect their families started questioning their decisions of sacrificial spirit when they received the letters from their families. Their living conditions were getting worse, and the wives with small children were at a loss when they received the order to be evicted.

“We were devastated,” they said. “This was a terrible government family-separation policy.”

The BCSC (British Colombia Security Commission), which was entrusted with the total movement, kept only the men who could be Japanese operatives away from the coast. They eliminated the risk of rebelling against Canada by becoming the fifth column if the Japanese troops attacked the west coast. On the other hand, they forcibly moved the remaining women and children inland to separate from the men. This movement might have meant that they also deceived the boss of the Japanese society, who connected with BCSC, but there was no way of finding out since everyone was deceased.

As a result, most men who voluntarily joined the road camps were Issei, the first generation. Mr. Kawashiri witnessed that Issei—who called themselves the hardliners’ nationalists—bullied the Nisei, the second generation, who were not good at Japanese. He was a liaison between these two generations during this time, and he must have thought about the future of Nikkei society.

“…there were moderates and hardliners among the same Japanese, and some were uncooperative because they believed that Japan would win and did not want to get pushed around by the white people. Half of the 108 men were like that, and they did not want to be ‘dogs’ which listened to the white people.”

Then time passed, and in the spring of 1945, the Canadian government asked the Nikkei if they would remain in Canada to be loyal by reestablishing in the east or deported to Japan following the war’s end. Mr. Kawashiri replied clearly at the general meeting in Popoff camp that he would remain in Canada for the sake of Nisei, who grew up as Canadians.

As expected, Mr. Kawashiri was surrounded by angry nationalists the next day. However, he defended himself and said, “No one can doubt my patriotism for Japan, but immigrants have a mission as immigrants. Isn’t it a shame when the war was over, and there weren’t any Japanese when the Japanese came to Canada?” The nationalists were deeply convinced and left after his speech, because they interpreted the word “when the war was over” as “when Japan won the war.” The reason was that the Nikkei society believed in the rumor by consular officials that people in the camp would receive compensation of 350,000 yen after the war.

On the other hand, Mr. Kawashiri knew that Japan had no chance of winning by reading Canadian newspapers. He saw that people believed in the rumor and manipulated them. His keen insight was that the Nisei, who had grown as Canadian citizens, had become the bearers of Nikkei society from the Issei, who were loyal to the emperor and showed patriotism for Japan.

There was an anecdote that showed Mr. Kawashiri’s point of view. Mr. Tomekichi Honma appealed to the court to give voting rights to the naturalized Nikkei in 1900 and lost the proceedings after three attempts.

Mr. Kawashiri made his condolences at the funeral of Mr. Honma, who died in the Slocan camp in 1945. He ended his speech by saying, “Mr. Honma left this world without seeing the results of what he wanted to achieve, but there are still many people who remain in Canada and fight. One day, what you were trying to do will be achieved.” (Nikkei Voice, September 1993 issue). Mr. Kawashiri might have realized the end of the Issei era and entrusted his dreams to the second generation then.

All Nikkei received the right to vote three years after the war ended. Therefore, Nikkei gained all their rights as Canadian citizens.

To be continued ... >>

© 2022 Yusuke Tanaka