February 19, 1942, when Executive Order 9066 was issued, is the “Day of Remembrance” for Japanese Americans. This day should never be forgotten. For Japanese Canadians, February 26, 1942—or Order-in-Council P.C. 1486—would be the equivalent. This year marks 80 years since the internment of Nikkei. By focusing on the stories of Issei and Nisei leaders in particular, this three-part series introduces their history to reveal how the Japanese Canadian community was pulled into the war.

* * * * *

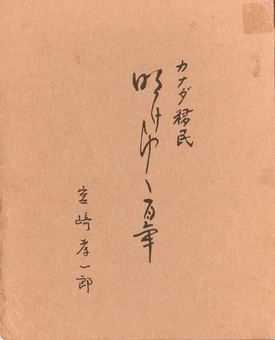

On the morning of December 7, 1941, the Pearl Harbor attack turned the life of Nikkei upside down. Koichiro Miyazaki, who is the principal of Fairview Japanese Language School in Vancouver, writes about “the morning” in his book Akeyuku hyakunen (Canadian Immigrants—Revealing 100 Years):

The moment I turned on the radio to listen to a morning program, I gasped in shock. And I turned it off, just to get it out of my mind. In the kitchen, my wife was busily washing the dishes.

“They will start a war!” My voice was shaking.

“Oh,” she responded rather nonchalantly.

“Japan did that to America…”

“What’s going on?” my wife asked, as she turned back to me.

“It seems like Japan attacked Hawaii.”

“No way,” she said without showing much interest, as she put the dishes down.

“Could it have been some mistake...? I thought that’s what I heard on the radio just now...”

“I’m pretty sure you misheard it. That’s very possible considering the level of your English,” she said with a laugh, to her husband who wasn’t sure about what he’d heard, as she kept washing the dishes.

To find out the truth, Miyazaki called a newspaper publisher.

“...you must have heard something wrong,” said Editor-in-chief* as he burst out laughing.

That’s how shockingly unexpected it was. (*Editor-in-chief must have been Yoriki Iwasaki of Tairiku Nippo [Continental Daily News])

At the time, the majority of Issei were workers in their 20s and 30s. They were fighting hard to keep their Japanese pride, confronting the obstacles of being in a different culture and facing racial discrimination. As the Japanese invasion of China dragged on, the North American society began to reveal their hostility to Nikkei more bluntly. We can see in the fear they faced how the life of Issei was continually shaken by various political circumstances.

The Issei in the prewar time could be broadly divided into two types. The majority of Issei were like Koichiro Miyazaki who would be considered extreme patriots believing in shinkoku (divine) Japan, while some people like Chiyokichi Ariga, the principal of a Japanese language school of Haney Farmer’s Association whom I will introduce here, tried to keep their ethnic identity as they assimilated into the Christian culture in Canada at the same time. Ironically, the ones who got arrested first by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) as suspected spies once the war started were those Japanese teachers who served to build a bridge between Japan and Canada.

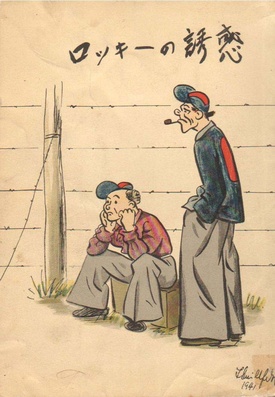

The following excerpt is from the first chapter of Rocky no yuuwaku (Temptation of Rocky, 1952) by Chiyokichi Ariga.

●To assimilate or to swear loyalty to Japan

Five days after the Pearl Harbor attack, a RCMP car arrived at my place and they asked me, “Are you Mr. Ariga?” when I was opening the mailbox outside our house. “We would like you to come with us to Vancouver,” they said.

“Dad, where are you going?”

Ariga was “crying” inside, as he had to leave his daughter who was prone to getting sick. What he had expected to be a few days of interrogation was the start of his two years and some months of life as a war prisoner.

As they began to slowly rcover from the shock in the immediate aftermath of the war outbreak, many Issei were thinking in their hearts, “They finally did it!” and “I feel so light-hearted that I want to whistle.” (From Akeyuku hyakunen) To say goodbye, Miyazaki stopped by at his Caucasian friend’s house, told them he would go to internment camp, and asked them to look after his wife and kid, but in his mind he told himself that it was a war that “could not be lost.” (From Nikkei canada-jin [Nikkei Canadians] by Shinichi Tsuji)

On the other hand, Ariga was teaching students to “become good Canadians.” He objected to the RCMP in the interrogation, asking, “Why did you arrest me?” Then the interrogator answered, “A principal at a Japanese language school is a big man.” But it wasn’t that they arrested all principals of 59 Japanese language schools across the province of British Columbia. Nor did they arrest all editors-in-chief at Japanese newspaper publishers. Maybe we can define the term “big man” as someone who was deemed potentially capable of controlling people in the fifth column and thus considered a persona non grota. It was probably a term that the officer had to force out in response to Ariga’s challenging question.

There were in fact a lot more “key” figures, but those people were “intentionally excluded from the list that was handed to the RCMP by some informers.” (From Ishi wo mote owaruru gotoku [As if chased out by getting rocks thrown at] by Mitsuru Shinpo) A question comes to mind: Who were those “some informers” that made the list of people to be arrested by the RCMP, and what were their criteria? There’s no source left to find a solid answer. But we can guess to some extent what might have contributed to their act by looking at the circumstances of the Nikkei community back then, comparing the autobiographies of Chiyokichi Ariga and Koichiro Miyazaki to Nikkei kanada-jin no nihongo kyouiku (Japanese Education of Nikkei Canadians) cowritten by Tsutae Sato, principal of Vancouver Japanese Language School, and Hanako Sato.

In 1921, the board of education in Vancouver pointed out that the graduates of kokumin gakkou (Japanese National elementary school) were not proficient enough in their English skills to understand the classes taught in local high schools. This ended the full-time education that was aligned with the curriculum of the Ministry of Education, made the schools change their names to “Japanese Language School” and switch their principle of being “Japan-primary, Caucasian-secondary” to “Caucasian-primary, Japan-secondary.” From that point, Nisei started going to Japanese language schools and spent two hours there every day after they finished classes at local public schools.

This is how Japanese language schools led people to assimilate into Canadian society. Once the National Security Law was enacted in 1925, the media reporting from Japan got monitored and regulated, rapidly becoming patriotic. And the teachers at Japanese language schools, too, started teaching the emperor-centered, imperial ideology after the Manchurian Incident, telling Nisei, “Japan is fighting to build peace in East Asia” and “Don’t forget that you have the blood of the Yamato race in you even if you live a life abiding by Canadian laws.” However, there were some Nisei like Shinobu Higashi (who later became an editor at The New Canadian) who didn’t like to hear such preaching and said he “delivered the newspaper Minshu which was published by Japanese Labor Union just so he could skip classes at his Japanese language school.”

Asahi Team’s catcher Ken Kutsukake said that the prewar baseball field “was like a battlefield.” At the championship game in 1930, a Caucasian pitcher in the opponent team hit three Asahi players in their heads by his pitch, making them fall unconscious, and the game turned into chaos with spectators running into the field. After the Manchurian Incident in 1931, as the Japanese invasion of China prolonged, Nikkei went crazy over the victory of the Asahi Team as if it was the victory of Japanese military.

In 1936, at the playoff championship of the Commercial League, fans from both teams surged into the field after an Asahi player was ruled out on the home plate. They started having fistfights, resulting in the cancellation of the game. For using violence against the umpire and injuring him, the player Naggie Nishihara was sued afterwards. (from Vancouver Asahi monogatari [The Story of Vancouver Asahi] by Norio Goto)

It took a month to settle this disturbing case over the treatment of player Naggie Nishihara. It was Etsuji Morii, the ultimate boss of the Nikkei community who had connections with the RCMP, that helped settle the dispute as a mediator. Morii was the manager of the gambling house “Showa Club” and owner of the judo dojo “Kido-kan.” At Kido-kan, he was teaching judo to police officers, entrusted by the RCMP.

Morii had a long-term relationship with the RCMP. In 1931, when they made a mass arrest of 2,500 Japanese who had illegally entered and stayed in the country using fabricated documents, it was Boss Morii who cooperated with the police in their investigation. Morii was also known for his other face as a celebrity who donated the money he made at his gambling house to Japanese language schools. At other times, he made speeches telling people to “support the shinkoku (divine) Japan fighting its holy war,” claiming that he represented the Canadian branch of the political organization “Kokuryu-kai”; at some other times, he encouraged people to purchase war bonds for the Canadian government.

In his book The Enemy That Never Was, Ken Adachi writes in detail about Morii’s behaviors during the chaotic period that lasted until the “total evacuation.” He says that Morii could have been a “Pawn or scapegoat, a saint or a Villain, racketeer or a philanthropist—Morii was probably all of these.”

To be continued ... >>

© 2022 Yusuke Tanaka