Iris Yamaoka actually started her film career before her older brother Otto. She was a less prolific performer than her elder brother, perhaps because as a Nisei woman she faced gender as well as racial stereotyping. Still, her film career was most interesting in its own right.

Iris Yamaoka was born in Seattle in 1910—she was the second youngest and only daughter of the six Yamaoka siblings. She was still in her teens when she moved to Hollywood and had her first film roles, opposite the Japanese-born acting star Sojin Kamiyama.

In 1929, at the dawn of the sound age, she appeared as Foo, a Chinese woman, with Kamiyama and with Albert Valentino (Rudolph’s older brother) in a Chinese adventure story, China Slaver. She was signed to a contract by Universal Studios—in fact, her first assignment was dubbing dialogue from the Universal film King of Jazz, starring Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra, into Japanese. According to one report, the studio then planned a series of “exotic” shorts for her (including “Siamese Twins”, which appears never to have been made, and “Peeking in Peking” , which was ultimately filmed with actress Toshia Mori).

In fact Iris Yamaoka’s first credited role was in Paramount Studios’ Hell and High Water (1933), starring Richard Arlen. In that film, Suisei Matsui, a noted Japanese benshi [live narrator of silent films] who had come to Hollywood, played the role of a Japanese fisherman. (Ironically, Matsui was coached for his role by Eddie Holden, the star of a popular radio series of the time, “Frank Watanabe,” in which he portrayed a Japanese American character). Iris Yamaoka appears as Matsui’s wife from Japan, a Japanese fishing village girl. Although Iris Yamaoka’s screen time was small, Larry Tajiri later noted that Hell and High Water gave her a chance at “a portrayal a bit longer than the average allotted an almond-eyed emoter on Hollywood's sound stages.”

However, Buddy Uno may have identified a problem for Iris Yamaoka—unlike her brother Otto, who delighted in speaking Japanese and who was able to carry off a “Japanese” accent, Iris lacked the accent and demeanor required to portray a Japanese immigrant. “Iris Yamaoka, Joe’s bride-to-be, was a pitiful example of how impossible it is for a second-generation girl to portray [a] newly arrived Japanese girl in this country…Those who saw her in ‘Hell and High Water’ will undoubtedly agree with me.”

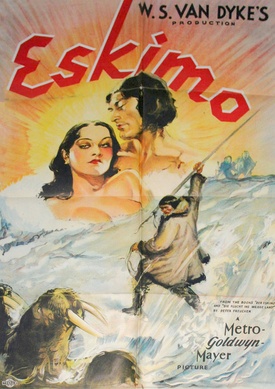

Perhaps Iris Yamaoka’s most significant role was in the 1933 MGM film Eskimo, directed by W.S. Van Dyke, with the native Alaskan actor Mala (Ray Wise) in the lead role as an Inupiat [then known as Eskimo]. The mixed-race Nisei actress Lotus Long (Pearl Suetomi) played the second lead. Iris was given the role of Nana, one of the hero’s wives.

One notable point about the film is that it was shot in Point Barrow, Alaska, in a period when on-location shooting was a relatively rare thing. The film was also unusual for the times in featuring Inupiat language and customs—though of questionable authenticity. Iris Yamaoka spent 11 months filming in Alaska.

As a report in the Japanese American press put it, “With more than 40 others, she was much farther north than is generally known. Before she began work with the camera, they gave her an opportunity to study the daily life of the Eskimo. In her acting, she was allowed to be original and natural. Her eyebrows weren't plucked but her eyes were emphasized and this is the only makeup she had to bother with.” Another review noted of Iris Yamaoka that “she enacts the part of an Eskimo girl with artistry and nuance, even in one scene where she rubs noses with her lover in place of kissing.”

After completing filming on Eskimo, Iris Yamaoka returned to Hollywood, where she played bit parts in Pursued (1934) and High Tension (1936). She also served as a guide and companion for Japanese princess Toyo Togukawa when she did a movie studio tour during her family’s visit to Los Angeles.

In 1935, Iris Yamaoka accompanied her mother on a 19-day trip to Japan, where she was hosted by K. Mikimoto, the “Pearl King” of the Mikimoto company (with whom Yamaoka’s family members in New York were associated). She was featured in several articles in the Japanese press, and her acting performances were praised. The writer of a feature in the Japan Times, who held an interview in Tokyo with her just before she sailed back to this country, described her as having LARGE, EXPRESSIVE EYES.

In 1936, Iris Yamaoka was featured in Petticoat Fever. Like her brother Otto, she portrayed an Inuit in the film (their only joint screen appearance). Iris’s character, “Little Seal,” appears together with another woman, “Big Seal” (played by Chinese American actress Bo China). Iris Yamaoka was able to show off her diverse talents as “Little Seal”: she dances a “Labrador Hula,” and later is carried off by Reginald Owen, who mistakes her (buried in a heavy fur coat) for Irene Campton (played by Myrna Loy), thereby providing a rich comedy sequence. Mildred Martin, writing in the Philadelphia Inquirer, praised the role as “capitally played.”

After Petticoat Fever, Iris Yamaoka’s career, like her brother’s, went into decline. Her last credited role was in the 1937 film Waikiki Wedding, staring Bing Crosby and Martha Raye, in which she played an Asian American secretary.

At some point she moved to San Diego for a time. In the late 1930s, she worked with the local JACL chapter in Los Angeles, and helped present Japanese shrubs at women’s club events. By 1940, she was living with her mother in Los Angeles, and working as a saleslady in a fruit store.

Like her siblings, Iris was removed from her home under Executive Order 9066 and confined at Santa Anita and then at Heart Mountain. She was also the first of her family to get leave clearance, and she departed with her mother at the end of May 1943. The two moved to New York, where they had family members, and settled in the Riverdale district in the Bronx. Once in New York, Iris Yamaoka took a job with the Methodist Committee for Overseas Relief as chief bookkeeper. She was still employed by them at the time of her death in late 1960.

Both Otto and Iris Yamaoka, like the rest of the ethnic Japanese (and other Asian) actors in prewar Hollywood, played many kinds of roles, both in ethnic and professional terms. Like the African American screen performers of their day, they had little control over what parts they played or how they would be portrayed. Again like African Americans, Otto Yamaoka was most often typecast in his films as a comic servant—at first, mainly in Japanese roles, but then increasingly as a Chinese. This reflected the little world in which elite white creative artists and studio officials lived—a world where Asian American valets and domestic laborers were common. It may also suggest that they thought of the existence of nonwhite Americans as somehow inherently funny.

Iris Yamaoka, a woman who did not easily fit ether the domestic or the immigrant “type,” made her biggest impression playing Inuit women. It is sad that both siblings died relatively young, before they could be rediscovered by a new generation of Asian American performers and audiences.

© 2022 Greg Robinson