According to Ken Adachi’s The Enemy That Never Was, there were about 1,500 Japanese-Canadians in Japan at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack (1941). Deprived of a chance to return home, many of them were labeled “hostile citizens” and were relentlessly told by the authorities to change their nationality to Japanese. Among the former members of the Vancouver Asahi who joined the Japanese military were Tamio Noda (died in war) in Wakayama and Ken Nakanishi (wounded in war) in Hiroshima.

With English skills under their belt, there were at least a few Nisei Canadians who got jobs in the media industry as well. Kazuma Ueno, after graduating from the University of British Columbia, got a scholarship from the Japanese government to go to Japan and worked as an anchor at NHK in Shanghai. There was Shinobu Higashi, former editor-in-chief at The New Canadian who worked at national policy promotor and English paper, the Daily Manchuria, in Hsinking, Manchuria (current Changchun). And NHK in Tokyo had Satoshi Nakamura, former member and home-run king of the Asahi team who made an English radio program called “Zero Hour.”

In addition, we should not forget Aiko Saita in the entertainment industry who joined the Fujiwara Opera Company and visited a number of battlefields as a singer. Aiko and Satoshi spent their youth together in Japantown on Powell Street.

I think that the Nisei who were living in Japan back in the day were all highly talented. I would assume that they all had the same feeling about their future, having been educated in prewar Canada, that staying in British Columbia would not grant them the income and social status they deserved, because of the systematic racism. As they officially became adults, they decided to move to Japan to find their future there.

Go east

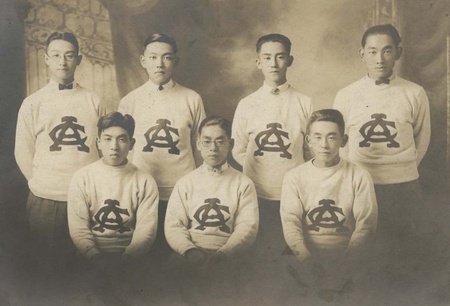

In 1908, Satoshi was born on Powell Street in Vancouver, and his early life was dedicated to baseball. In 1926, he won the Terminal League Championship for the first time as an official member of the Asahi. At 18, Satoshi was a rookie and home-run king at the same time. And Asahi’s league championship in 1930 was the start of their unstoppable and successful team record.

Japan on the other hand was in turmoil from the war which was triggered by the Manchurian Incident, and an emperor-centered education was implemented all over the country.

Around that time, Nisei were coming of age. In 1932, the Japanese Canadian Citizens League (JCCL) was formed, with the majority of members being the Nisei students at the University of British Columbia. Their mission was to abolish the systematic racism and earn their voting rights. In 1936, in pursuit of voting rights, JCCL sent a group of four Nisei petitioners to Ottawa, with Samuel Hayakawa as the leader.

Hayakawa (who later became a US Senator), with a MA in English from McGill University in Quebec, had already been teaching in the U.S. as a college professor and apparently was a role model for many Nisei. He urged the Nisei students to “go east” – this is because there was less discrimination in schools in the east of Canada, where medical and law schools were more accepting of people of Asian descent.

Meanwhile, Satoshi unfortunately was forced to give up on baseball at age 24 because of a shoulder injury. But he didn’t let it bring him down; instead, he took notice of his second gift from god, so to speak, and decided to become an opera singer with his baritone voice, a kind that’s a bit unusual for the Japanese to have.

He was living in the 1920s when American culture was just about to bloom. The popularity lied in the elegant melody and arrangement created with the fusion of classical music, such as Gershwin’s, and the blues music of blacks, and the singers who nailed those songs as well as big bands. It was pure luck that one of the regulars of the hotel where Satoshi worked as a bellboy turned out to be a prominent vocal coach. He accepted Satoshi’s passion and took him as a pupil; it was a miraculous episode of him becoming a pupil of a white classical singer.

Satoshi who followed the “Go east” flow and came to Japan in 1940 had another bit of luck. He met his teenage friend Aiko Saita who was discovered by the pioneer of the Japanese opera, Yoshie Fujiwara, and had debuted in Japan. Perhaps Aiko, too, knew that staying in North America would not give her a chance to stand on the big stage. In many regards, she helped Satoshi in Japan.

Then came the Pearl Harbor attack. English songs got banned, and Satoshi had no choice but to give up on his singing career, and he decided to become a movie actor. But all he was offered were small roles such as a suspicious Asian or an interpreter who interrogates captives. As Japan’s defeat became clearer, even those roles thinned out and he was no longer able to make ends meet. It was just around the time when he got an offer from NHK for his English fluency.

He was hired to be part of the production team of “Zero Hour,” a radio program intended to make American soldiers in battlefields lose their fighting spirit. They would read the letters of captive soldiers writing for people back at home and have women say lines such as “I’m sure your wife is enjoying an affair with another man at this moment” in a luscious voice with nostalgic country songs playing in the background - all to make the intended listeners anxious. Who would have thought that one of the female announcers, Japanese American Iva Toguri would be sent to prison after the war for national treason?

Coming under the spotlight

On August 15, 1945, Japan accepted an unconditional surrender. What followed after was a peculiar turn of events for the Nisei where everything flip-flopped in a moment. Their status changed from being the Japanese in a defeated nation to the ones on the winning side.

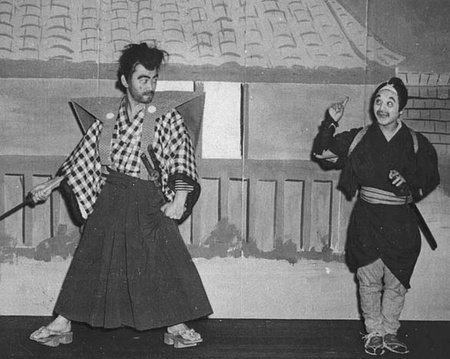

There were 730 bases of the Allied Occupation forces in Japan and “while ordinary people had no houses and suffered from starvation, inside the American bases and the clubs around them where Japanese musicians performing unregulated, boisterous, gaudy shows day and night, as if to release all the frustration over the longtime ban on what was considered the music of the enemy.” And Sally Nakamura, with his great singing skills that enabled him to perform a wide variety of songs from classical music to pop, came under the center of the spotlight as a top-notch singer at clubs targeting senior officers. Earning applause from white people would have been almost impossible in Canada.

Sally Nakamura’s prime was probably when he was singing “Ol’ Man River” and “Danny Boy” with Nobuo Hara and his Sharps and Flats in the back. And the highlight of it was undoubtedly the musical in four acts My Old Kentucky Home (1947) where Satoshi played the protagonist with screen diva Li Xiang Lan (Yoshiko Yamaguchi) at the Imperial Theatre. It’s a story of composer Stephen Foster in his not so bright years, and Satoshi happened to have Foster’s songs in his repertoire. The casting must have been the best they could have imagined, in terms of popularity and ability, with Satoshi as Foster the protagonist and Li Xiang Lan as his wife. We should probably note here that Yoshiko Yamaguchi was born and raised in Mukden, China. In other words, the two major cast members were both Nisei, born and raised in foreign countries.

The singers who stood on stage in military bases eventually came to define the J-pop industry. Among them were Dick Mine and Peggy Hayama who were the forerunners, and many others followed their path, including Mieko Hirota who was still in middle school at the time, Frank Nagai who later became the legend of Japanese blues ballads, and Kazuko Matsuo – quite a few of them have passed away.

Satoshi Nakamura, who had resumed acting by then, played supporting roles in a number of films created during the golden age of film-making after the war. The most notable one was probably Red Sun (directed by Terence Young) made in 1970. Satoshi played the role of a minister who visits America as he is guarded by a samurai played by Toshiro Mifune, and he acted in the film with glittering stars like Alain Delon and Charles Bronson.

“Entertainer under the occupation”

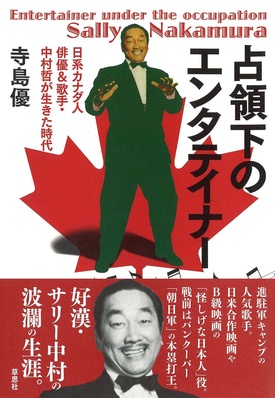

Yu Terashima, Satoshi Nakamura’s son, wrote the book “Senryōka no entateinā: nikkei kanadajin haiyū & kashu nakamura satoshi ga ikita jidai (Entertainer under the occupation: Sally Nakamura)” in 2020. For those who are 70 years or older, it’s one-of-a-kind, as it’s full of retro-flavored stuff.

If you allow me to talk about myself, around 1972 when I was a student, I was playing the bass guitar in a band of 7 members in a club in Ginza. A variety of singers appeared on stage performing good-old songs day by day, and Dick Mine was one of them. He sang “Dinah” which was a megahit before the war and I still remember being nervous, performing with such a legendary singer.

The Allied Occupation forces left Japan at once in 1952 after the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Ten years later, a rise of folk music came from the U.S., bringing antiwar sentiment. Satoshi emceed the legendary concert of Peter, Paul & Mary. Satoshi’s son, Yu Terashima, said it was this work of his father that made him change his view on him and feel proud of his father for the first time.

This book is based on a thorough research of Yu Terashima who is the son of Satoshi Nakamura and now works as an original manga story writer. His research covers so many details, from written accounts on Nikkei history, interviews with people surrounding the Nakamura family, Satoshi’s life in Vancouver before the war, to the couple’s appearance in a TV commercial in their later years. While reading it, I was surprised to find Satoshi’s nephew and public figure David Suzuki, depicted as an important mentor who helped lead the Nakamura family.

The life of immigrants is constantly affected by the change in the relationship between their home country and the society they live in. Satoshi Nakamura as a Nisei might have not been able to settle in either place, though he was physically able to live in both, and his identity might have kept swinging like a pendulum. He couldn’t deny his yearnings for Canada but the tie had been broken. The image of Satoshi Nakamura from his son’s perspective makes me think about a rootless weed in the water swaying in the wind. The truth of the matter is that I saw myself as an immigrant who resonated with it.

*This article in Japanese was originally published in the March edition of Fraser Monthly in 2021 and has been revised with some parts added to it.

© 2021 Yusuke Tanaka