The Japanese verb Sumu consists of three homonyms which include 住む (to live), 澄む (to become clear), and 済む (to finish). These three homonyms were etymologically derived from the same verb. If you try to put these three on a timeline, then you will see a time flow of past, present, and future; the flow slowly descends in-motion to a halt, or the process of settling in a place, purifying the mind, and the life finishes. People call it “大往生 (die-oojo)”— a great life and death with dignity.

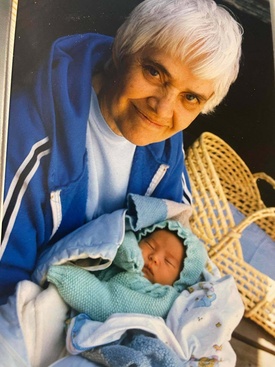

In July 2019, Kathleen Goring, a Canadian, passed away at the age of 94 years old. She had a great life and died with dignity. Her passing was mourned by many people. In particular her grandson Hiroki Tanaka—who had also been her caregiver towards the end of her life—had complex feelings as he saw her health gradually declining. After her death, Hiroki, also a musician, tried to unravel his experiences as a caregiver and grandson through words and melodies, making them into an album.

The title of the album was named Kaigo Kioku Kyoku (translated as Caregiving Memory Songs). There might be a reason why he called it “Kioku Kyoku or memory songs,” and not “Kaiso Kyoku or songs of reminiscence” because the lyrics do not carry a taste of reminiscing or beautifying of memories. Instead, still raw pain and poignant memories are stuffed into the lyrics that include the voices of Japanese volunteers at the senior’s home where Kathleen spent her last days, singing old Japanese children’s songs, the sound of a coo-coo clock from her house, the tap water dripping in the sink, dishes jostling in the sink and the sound of a gong that opened many a homemade dinner at Kathleen’s house.

In addition to all these slices of Kathleen’s soundscape, is a harp rendition of a hymn “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence” performed by Jacqueline Goring, Kathleen’s daughter. A hymn which used to echo in St. Barnabas Church, the church where Kathleen’s husband, Rev. Vince Goring, had served as minister from the early 1980s until 1990. All these sounds were carved into the memory of this multi-generational house.

In 1988, Hiroki was born in a small house in the Upper Beaches area of Toronto. His mother was Deirdre, Kathleen’s eldest daughter. She was a Japanese English interpreter. His father, Yusuke, myself, was working as a Japanese writer in Canada. Later in the same house, his grandparents lived until their final years of life. After Kathleen was predeceased by her husband, Vince, she herself began to lose her health. Until she lost her mobility, the role of her caregiving was provided by several caregivers including her granddaughter, Sonomi, and then grandson Hiroki. So it was that her house, located in the east end of Toronto, was resided by three generations of a family, one after another. When the house was finally emptied for sale, musician Hiroki could not help but fill the bare hallways of the house with his words and melody which rang of the emptiness he felt.

I am proud of him and deeply grateful to him for creating an ever-lasting requiem for the mother-in-law I so admired.

Looking back on Kathleen’s life, she showed an abundance of mercy and generosity to the people around her, which was based on her strong faith. When I decided to divorce, she hugged me and told me, “Whatever happens, you are my son.” Her words encouraged me to move forward.

Canadian Missionaries

In 1888, the Anglican Church of Canada began to send missionaries to Japan following the first missionary posted in Nagoya. In 1913, they opened the Canadian Academy in Kobe. Rev. Percival Powles and his wife Ruth were posted in Takada (current Jo-etsu), Niigata Prefecture in 1916, where they built their church and raised five children, educating them by correspondence.

In 1932, the Anglican Church of Canada invested 2 billion yen in current rate and built a New Life Sanatorium in Obuse, Nagano Prefecture. Rev. Powles had been deeply committed to the management of this tubercular sanatorium. In 1968, this facility was renamed New Life Hospital as the result of decreasing number of tubercular patients and the hospital is still in operation there.

There was another Canadian missionary family in Japan, Rev. Daniel Norman and his family. These two families, the Normans’ and the Powles’, enjoyed summer vacations on Lake Nojiri. Rev Norman’s second son Herbert came back to Japan as a Canadian diplomat and he was said to be the most trusted advisor for General MacArthur, the head of GHQ in Tokyo.

One of the friends Herbert used to spend time with at Lake Nojiri was Cyril Powles, the eldest son of the Powles Family. Cyril grew up to become a theologist and returned to Japan to serve as a missionary like his father. Later Rev. Cyril Powles became known as one of the founders of Japan Studies in Canada and he taught the history of Christianity in Asia until he finished his academic career as the Dean of Trinity College in the University of Toronto. He used to volunteer as the chief judge of the annual Ontario Japanese Speech Contest.

Daughter of Missionaries

The late Kathleen Goring was born in 1924 in Takada, Niigata Prefecture as the second daughter of Powles family and was raised in Japan until she turned 13 years old. In 1937, she came back to Canada and later entered McGill University in Montreal to study Latin Language. During WWII, the Powles Family looked after Japanese Canadians who were being relocated from the west of Canada to Montreal, providing housing and jobs for them.

When I went to Montreal to attend a Japanese Canadian conference in 1995, I asked some local people if they remembered the Powles family. I was surrounded by a group of local seniors and was asked many questions about how the Powles family was doing. Each senior spoke of fond memories of the family. It’s no wonder if they recalled them vividly because when they arrived in Francophone Montreal for the first time with fear and anxiety, the Powles family were among the few white people who greeted the new comers at the station with a smile and speaking Japanese, putting them at ease.

In those days, the living room of the Powles family was used as the meeting place for Japanese Canadians. Kathleen once told me of her memory one day when she was having some difficulty ironing the military uniform of her brother Bill. Seeing this, a visiting Japanese Canadian gentleman spoke to her saying, “May I help you? I am a dry-cleaner by trade.” Kathleen marveled at the deftness of his skill.

Kathleen met her future husband Vincent Goring at McGill University through the Student Christian Movement. In 1963, Rev. Goring and his family were dispatched to Kyoto, Japan as missionaries. For Kathleen, it was a home-coming to where she was born. Her Japanese speaking ability must have made her family members feel secure in Japan and helped them communicate with local people. Rev. Sam Koshiishi, former director at the Head Quarters of the Anglican Church of Japan, used to tell me that he was in awe of so many of Kathleen’s qualities.

In a sense, she was the most “Traditional Japanese” lady I have ever met in Canada. She appeared to be always quiet and reserved and did not act too sociable in front of others. However, she was said to be very stubborn and did not bend her opinion easily. I remember her husband Vincent once told me so with a chuckle.

Kathleen grew up in Japan and the family returned to Montreal only when signs of the pending war began to creep into daily life. When we talked about her life before WWII, the only time her face clouded over was when she talked about a bunch of Japanese police men who rushed into her house to investigate the family. She spoke about how she had never felt so scared before in her life and said, “As they came in, the air was filled with evil.” During the wartime, her mother Ruth and her older brother Cyril visited the internment camps of Japanese Canadians to check their health conditions and to consult with them in Japanese. Cyril is known to have actively supported Japanese Canadians’ redress movement.

A Home for Three Generations

Life is strange. My son Hiroki eventually went back to the very house where he had been born and started looking after his grandmother as a care-giver. Back in the early 1980s, his uncle Bryan and his family bought and lived in that house selling to Kathleen and Vince before moving on. Years later Bryan returned to that same house after he was affected by cancer, which is where he spent most of his final days.

As well, myself and my family lived there for two years from 1987. On April 15, 1988, Hiroki was born in the room upstairs. After his birth, friends and relatives walked into the room carrying a cake with a candle on top of it and started singing “happy birthday!”

In 1989, the then retired grandparents of Hiroki moved into the house and in 2008, his grandfather Vincent passed away at the age of eighty-five. His surviving wife Kathleen continued to live in that house looked after by caregivers, her children and her grandchildren.

For nearly forty years, three generations’ lifetimes were carved into the walls of the semi-detached house. Recently, I heard that the house was sold and was beautifully renovated. Nevertheless, in the small backyard of the house where a pear tree stands, the placenta that held Hiroki in his mother’s womb is buried deep under the ground. The soil called him back to this house again, I thought, although the only person who can pinpoint the exact spot now would be me since I dug the hole.

* * * * *

The album Kaigo Kioku Kyoku was released in November, 2020 was reviewed by several media outlets which can be found on the internet. Among them, the piece written by Vivian Hua, a filmmaker and the chief editor of a Seattle-based web magazine Redefine got my attention. Check out her article here >>

© 2021 Yusuke Tanaka