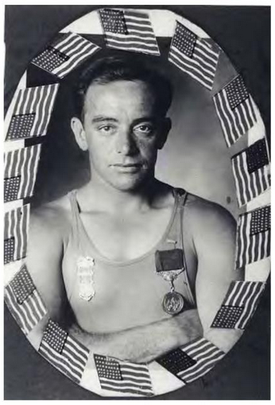

In December 1908, at the age of 25, the “father of surfing” George Freeth saved the lives of nine Japanese American and two Russian American fishermen off Venice beach when a violent Pacific storm lashed the coast. For his heroic actions, Freeth was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal for bravery.

In April 1919, at the age of 35, the Hawaiian-born Freeth—noted for his physical fitness and still in his prime—died after a long battle with the flu virus spreading across the globe. He was the first person to surf the Huntington Beach pier at its re-dedication in 1914.

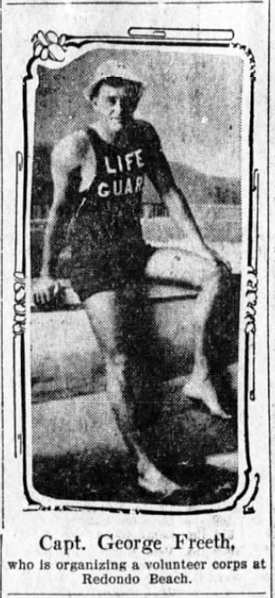

Freeth was a remarkably skilled surfer, the one Jack London described during his 1907 visit to Hawaii as “his heels are winged, and in them is the swiftness of the sea.” But, he isn't remembered just because he was a surfer. In Southern California, he was a local hero who dedicated his life to saving others.

On December 16, 1908, the “heavy northwester” hit the Southern California coast, catching local fishermen by surprise. Boats were floundering and being pushed toward the rocky breakwater. As a powerhouse alarm sounded, Freeth “made a spectacular dive from the wharf” into the water and swam to the most endangered boat first. The ocean water temperature off the coast of Los Angeles County in December averages a chilly 60°F (16°C).

The Los Angeles Times reported the next day that Freeth “successfully piloted the craft, which contained two Japanese fishermen, around the pier to a safe landing.” Freeth dove into the water repeatedly until he had helped eleven fishermen safely to shore. He crawled onto one of the Japanese American fishing boats and “by a trick known only to himself, piloted the craft through the surf at railroad speed and made a safe landing on the beach.” Freeth was a surfer and followed his instincts, surfing the boat to shore.

One Japanese American fishing boat capsized as they tried to make their way to shore, with three men falling overboard and too far ashore to be thrown a life buoy. Freeth again dove off the pier carrying a life belt for each of the three men so they could stay afloat until his volunteer lifeguards arrived by rescue boat. All were saved.

A few of the fishermen caught up in the storm were identified by the Los Angeles Times as T.O. Shiro, T. Caneshira, I. Igi, T. Yamauchi, Y. Kato, and T. Tokushima.1 The majority of the fishermen are identified as being from the small fishing village off present-day Pacific Palisades, in a beach area near the “Long Wharf” known as Maikura.

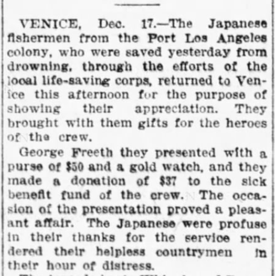

The day after Freeth's heroic rescue of the Maikura fishermen, they returned to see him, bearing gifts. In addition to a cash gift of $50—an equivalent of about $940 today—they presented Freeth with a gold watch (average price of a gold watch in 1918 was $12.93, an equivalent of about $240 today). They donated an additional $37 to the volunteer lifeguard benefit fund. The fishermen reportedly announced to Freeth that they were renaming Maikura as “Port Freeth” (Our L.A. County Lifeguard Family, LACoFD, Lifeguard Operations). A 1910 Los Angeles Times article about a Yamato Association picnic on the beach near the fishing village north of Port Los Angeles noted “which by some is called Freeth—so named in honor of George Freeth, the Hawaiian life-saver, who rescued a number of Japanese fishermen who were caught at sea during the storm of two years ago.”

Fast forward to 1918, a decade after his nationally-reported heroics rescuing the Japanese American fishermen, Freeth was working a lifeguard job at Ocean Beach in San Diego. He continued to demonstrate his surfing skills for awestruck beach crowds, including one stunt where he “suddenly leaped clearing the board by at least three feet, turned a sumersault, regained his balance on the board again, then completed his stunt with a dive. The trick was a thriller, and evoked a storm of applause.”

Months later in January 1919, Freeth was overtaken by the flu virus. The pandemic had taken root in the military bases in San Diego and, despite flu masks and a citywide quarantine in December 1918, the virus continued to spread in the surrounding community.

Freeth recovered, then relapsed, and was hospitalized again. He would not fully recover. On the evening of April 7, 1919, he passed. The Honolulu Star Bulletin reported on April 8, 1919, that “George Douglas Freeth, well known local athlete and swimmer, died at Ocean Beach, California, last night of pneumonia, according to a cablegram received by Honolulu relatives today. In December 1908, Freeth rescued nine Japanese fishermen during a storm at Venice, Cal., for which he was awarded the Congressional medal for heroism.”

During the 1918-1920 pandemic, the mortality was a “W” curve. The virus hit hardest those younger than five, 20-40 years old, and those sixty-five and older. Many who succumbed were fit and healthy before the virus, like George Freeth.

The number of lives lost during the 1918-1920 pandemic is estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,000 occurring in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The CDC also notes, “with no vaccine to protect against influenza infection and no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections that can be associated with influenza infections, control efforts worldwide were limited to non-pharmaceutical interventions such as isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, use of disinfectants, and limitations of public gatherings, which were applied unevenly.” (1918 Pandemic - H1N1 Virus, Centers for Disease Control)

George Freeth, the son of Elizabeth Kailikapuolono Green Freeth was laid to rest in the O'ahu Cemetery in Honolulu County, Hawaii after friends in California sent his ashes home to his mother. Freeth's legacy in Southern California is not just as the “father of surfing,” but also the lives he saved during his short time on earth. His story is one out of the millions of souls lost to the 1918-1920 virus.

At the time of this writing, the Huntington Beach pier that George Freeth famously surfed in 1914 is closed to limit public gatherings due to the global pandemic coronavirus, COVID-19. For those reading this in the present day, stay home. Flatten the curve.

Note:

1. Names of the Japanese American fishermen as spelled by the Los Angeles Times in 1908.

*This article was originally published on the Historic Wintersburg blog on March 25, 2020.

© 2020 Mary Urashima