In the last part, I wrote about Yoemon’s death from an unexpected accident and the family’s sorrowful return from Seattle to Kamai. In this part, I will write about how Aki recovered from sorrow, headed to Seattle again, and had her daughters come to the U.S.

Re-opening of Aki’s barbershop business

After Yoemon’s death, Aki lived desolate days in sorrow. Gradually she started to think that continuing to live and farm in Kamai would not do any good for her. Two years after Yoemon’s death, she decided to go to Seattle and make some money again.

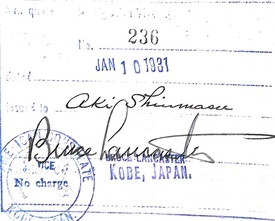

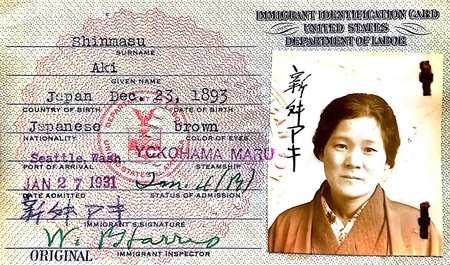

Ready for a restart, after spending New Year’s holidays in January, 1931, Aki left for Seattle alone, with many people in Kamai seeing her off. On the morning of her departure, she prayed at a Buddhist altar and told Yoemon about her decision to go to Seattle again. Aki felt as if Yoemon was giving her the push she needed. It was the start of 36-year-old Aki’s tremendous challenge.

She got on Yokohama-maru from Kobe on January 10 and arrived in Seattle on January 27. It was her fourth time traveling, since the first time she went to Seattle as a “picture bride” at age 18. It was a long, 2-week trip, but even the rough sea didn’t bother her. Many of her relatives and Yoemon’s friends gathered to welcome Aki at the Port of Seattle. The view of Seattle did not seem to have changed over two years. Aki was getting a bit emotional, as she had thought she would never be back again. She was thinking about starting a barbershop business again, the business that she devoted herself to for a long time with Yoemon.

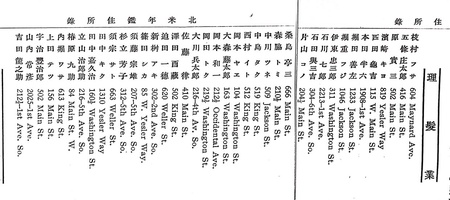

In a place not far from where she started a barbershop in the basement with Yoemon, Aki found a plain yet neat barbershop and opened her business. In the 1936 edition of Hokubei Nenkan (North American Almanac), as part of statistical data of 1935, we can find 39 names and addresses of Japanese people who ran barbershop businesses. The number of Japanese-owned barbershops in Seattle exceeded 100 at one point. However, at this point, many had returned to Japan, and the number had significantly dropped. In this list, we can find the line “Shinmasu Aki, Address 302-2nd Ave. So.”

Chuzaburo Ito’s name is also on this list. Working as chairperson of the barbershop business union and Yamaguchi Kenjinkai, since 1934 he had also been serving his third term as chairperson of Hokubei Nihonjinkai (North American Japanese Committee). While serving such important positions, Ito ran his own barbershop near Aki’s, always willing to support her. Ryunosuke Yoshida, with whom Yoemon ran his barbershop business together before their marriage, can also be found on the list. Ryunosuke’s shop was also located near Aki’s and he often visited her shop. As I introduced in Part 2, Ryunosuke is the father of Jim Yoshida who appears in The Two Worlds of Jim Yoshida. With support from many people including Ito, Yoemon’s friends, relatives, and her peers, Aki was able to run her barbershop.

I noticed something about the list. Of 39 names listed, 16 of them were female business owners, accounting for 41% of the total. According to the 1936 edition of Hokubei Nenkan, there were nearly 1,400 Japan-born women in Seattle in 1935. About 100 of them had lost their husbands like Aki. It seems that those who were running a barbershop business alone were in a similar situation as Aki.

Japanese-owned barbershops were mostly run by couples, and shaving was the wife’s job. I wrote in Part 3 that gentle touch and service with great care attracted Caucasian customers. Around 1916 when Yoemon and Aki were running their shop together, and in other Japanese-owned barbershops, too, women were considered as supporters of their male partners. By around 1935, Japanese women in Seattle had earned a reputation for their skills, making it possible for them to run a business on their own. As such, we could find a community of active women in the labor force in Japanese-owned barbershops in Seattle. Aki was one of these powerful female owners.

Alone, Aki worked from early morning till late at night. As she had worked in the barbershop business for a long time with Yoemon, despite the two-year break, her skills were high enough to get the business going. Aki’s shop attracted a lot of people, just like when she was working with Yoemon. Some Caucasian regulars, too, upon hearing the opening of Aki’s business, came to the shop. Though she couldn’t communicate with them due to the language barrier, the Caucasians visited Aki’s shop with a smile.

I found the hair clipper that Aki was using at the time, in the house in Kamai. As she started working again in Seattle, Aki was slowly able to recover from the sorrow of losing Yoemon. There was a bill from when Aki bought a futon mattress at Furuya Shoten (Furuya Store) in Seattle’s Japantown in October, 1936, which helps me imagine her life around that time. Furuya Shoten was opened in 1892 by Masajiro Furuya as a general merchandise store and later became a big department store which sold many items including food products, furniture, Japanese-style variety goods, artworks, books, and shoes and eventually turned into a giant company handling shipping business and banking duties.

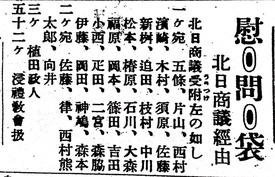

In the Great Northern Daily News of October 12, 1937, there was an article about Aki making a donation with the name “care package” to Japan through the business chamber of North American Japanese Committee. Most of the people listed as donators in the paper were members of the barbershop business union. The business chamber of North American Japanese Committee was the name of the new Japanese committee, a merger between the previous North American Japanese Committee and Japanese business, which took place in 1931, and the new committee lasted until 1942. The Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937. This “care package” was sent to Japan and with daily use commodities put inside, it was used to give comfort to soldiers in the battlefields and to boost their morale. The article was published around the time when Japan was entering the war.

While keeping herself busy at work, Aki found time to write letters to her two daughters in Kamai. Though she was tough and resilient, living alone in downtown Seattle made Aki feel very lonely. Aki remembered that when she was young and running a barbershop business with Yoemon, she left her two daughters in Kamai as they became a nuisance to their business. There was nothing she could do about what she had done back then, but she wanted to call her two daughters over to Seattle once they graduated from school in Japan so they could live together.

Sisters’ re-entry to Seattle

Yoemon’s eldest daughter was born in Seattle on September 20, 1916. Her parents took the toddler daughter to their barbershop in Seattle’s Japantown, and she often played around the shop. But she was sent to Japan at age 4, as her parents found it difficult to do their work with small children, and she grew up in Kamai where her grandparents lived. Though she was living in Kamai, she felt nostalgic about her hometown Seattle. After graduating from a local elementary school, she entered the Hirao Koutou Jyogakkou (the Hirao girls’ school) in the mainland, across the ocean from the island. As she couldn’t commute from Kamai, she lived in a boarding house near the school. Aki sent her eldest daughter to this school to have her get an education and learn dressmaking. Aki herself moved to Seattle without even getting enough of an elementary school education, and she wanted her daughters to study and gain some skills. Aki wanted her eldest daughter to get the best education she could provide in Japan.

At the time, only some in the mainland were able to go to this girls’ school, and almost none could go from a poor village on an island like Kamai. Aki’s eldest daughter finished the practical course and graduated from Hirao Koutou Jyogakkou Zikka (Hirao Practical High School of Girls) in March, 1933. In a letter from her mother Aki in Seattle, she was asked to come over to Seattle after graduation. She read the letter and was very much looking forward to going back to her hometown Seattle and meeting her mother.

After graduating from the girls’ school, at age 18 she moved to the U.S. to be with Aki in April, 1935. She boarded Mie-maru from Kobe and headed to Seattle. Two weeks of traveling by ship brought her to Seattle, and Aki was there to pick her up. They had not seen each other for four years. It was a start of her new life in Seattle with much love from her mother, something that she had not been able to experience for a long time.

I found a photo of the two from when they went to Seattle Lincoln Park together in July, 1936. Mother and daughter were spending some quality time together in Seattle. It was a very happy time for Aki, living with her daughter. In the photo, Aki seems to be enjoying her time, wearing American-style light clothes. Aki missed her lost husband Yoemon, but she must have felt happy to have her daughter in her life again.

Aki’s second daughter was born in Seattle in 1918. At age 2, she was also sent to Japan just like her older sister. The second daughter remembered almost nothing about Seattle. Her childhood memory is a lonesome life in Kamai without parents.

Some years after her sister’s migration to the U.S., the second daughter, too, felt the desperate desire to go to Seattle where her mother lived. She visited Seattle and met her sister and Aki. Her sister took her around Seattle, and the three spent a family time together over meals. To her, the scenery of Seattle looked like something she had never seen before, despite that she was born there. After spending some time in Seattle, while very much reluctant to part with her family, she returned to Japan, with her sister and Aki seeing her off.

Aki and her eldest daughter’s return to Japan

In June, 1936, Aki’s eldest son Atae came to Seattle as well. Now Aki was able to live with Atae and her eldest daughter, the three of them together. Though her barbershop business was doing fine in Seattle, Seattle was no longer a safe place. The Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, giving a rise in political instability, and many started to talk about the possibility of a Japan-U.S. war. By around 1939, Aki had received a number of letters from Kamai, urging her to return to Japan.

Under such circumstances, Aki made a decision. She closed her barbershop, which she had run alone as a female owner for about eight years and went back to Japan with her eldest daughter on August 13, 1939. Aki felt deeply emotional about the fact that she was able to make a living for eight years in Seattle and thought that Yoemon must have looked upon her from above. The fact that her children came to Seattle and spent time with Aki gave her the greatest strength in heart.

There is a photo of Aki and her eldest daughter taken upon their return to Japan. In those days many people were returning to Japan. This photo was taken near the ship with many other returnees. Aki is on the right of the girl in white clothes in the center, and her eldest daughter is on the left of the girl. The eldest son Atae saw his mother Aki and his sister off, knowing that he would miss them a lot. Atae stayed in Seattle alone.

References:

Hokubei Nenkan (North American Almanac), Hokubei-jiji-sha, 1936 Edition

Kojiro Takeuchi, Beikoku seihokubu nihon iminshi (History of Japanese Immigrants in Northwestern America), Taihoku-nippo sha, 1929.

Mitsuhiro Sakaguchi, Nihonjin amerika iminshi (The History of Japanese Immigrants in America), Fuji shuppan, 2001.

*This series is a collaboration between Discover Nikkei and The North American Post, Seattle’s bilingual community newspaper. It is an excerpt from “Studies on Immigrants in Seattle – Thoughts on Yoemon Shinmasu’s Success of Barbershop Business,” the writer’s graduation thesis submitted at the Distance Learning Division at the Nihon University as a history major and has been edited for this publication.

© 2020 Ikuo Shinmasu