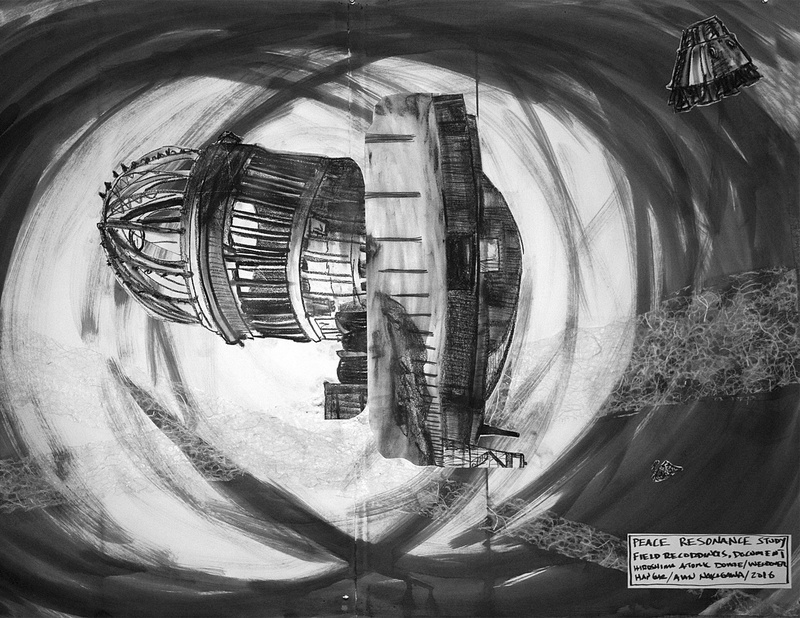

“You could feel everyone in the park staring,” Alan Nakagawa says. “Why do they get to go in the Dome? It was like being a goldfish in a goldfish bowl. However, the moment we were inside, having only an hour of access, we went straight to work.”

The Los Angeles native recalls the day he and videographer Tom Clancey walked into the Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima, Japan. The iconic structure, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the half-destroyed ruin of a building near the detonation point of the atomic bomb dropped on the city on August 6, 1945.

Nakagawa, an artist specializing in sound, had come to Japan to make an audio recording of the inside of the Dome—a high-security space not typically open to visitors.

“We met City staff and four guards,” Nakagawa says. “When a UNESCO site is entered, it’s supposed be guarded. Those are the rules. We were given safety hats, paid the guards, the gate was opened and we walked to the front of the Dome.”

“The pressure of not screwing up the recording was intense,” he says. “Especially because at our first meeting with the City earlier in the week, we were told that because of an incident earlier in the year, the UN had created even more strict rules for access and in fact there was a freeze on access approvals. I’ve had enough experiences were technology fails on you at the most unfortunate moment so we did bring back up hardware.”

The occasion had taken three years of planning and preparation. As he worked, he felt not only the weighty responsibility of being allowed into a sacred historical space but also faced strict time limitations.

“My field recordings are often 17 minutes,” Nakagawa explains. “It’s my favorite prime number. I placed recorders at three areas inside the Dome. While we were recording, we couldn’t make a sound. I wanted as clean a three-point recording as possible. Generally speaking, no one is allowed in the Dome. If you go in the Dome, you can’t move anything. It was 17 minutes of meditative observation. We were able to execute two recordings in the hour we were given.

“Inside the Dome, there’s an eco-system of flowers, grass, bugs (especially mosquitoes and butterflies) and birds,” he adds. “Although the City sounds penetrate and maneuver inside the Dome, there’s also a deep feeling of silence. It’s as if several worlds exist in there.”

After capturing the audio from inside Hiroshima’s Atomic Bomb Dome, Nakagawa combined it with audio he took inside an important hangar at Historic Wendover Airfield in Utah. The hangar had once housed the Enola Gay—the B-29 airplane that had dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

“I was surprised that the Wendover Hangar gave us access to do part two of the recording,” Nakagawa says. He credits a “whole crew of supporters” for helping him, especially the Center for Land Use Interpretation. “Without them, the entire piece may never have happened. The moment we finished the recording in the Hangar, that’s when I could really celebrate a milestone.”

The resulting art piece, Peace Resonance: Hiroshima/Wendover, 2018, was a remarkable and poignant work that immerses the listener in two meaningful spaces at once. The work is featured in Under a Mushroom Cloud: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Atomic Bomb, an exhibition at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. The exhibition was organized in partnership organized in partnership with the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and also features displays of artifacts from victims of the bombings.

The project was especially meaningful to Nakagawa because he has family ties to Hiroshima. His mother’s family was from the Hiroshima area, and came to Los Angeles after World War II, in 1957. He notes that there was very little mention in his family of the atomic bombing when he was growing up, and that he only gained a full appreciation for its personal significance later in life. But his interest in the arts began early.

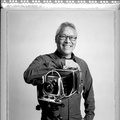

“I was born and raised in Los Angeles and was introduced to the visual arts, music and audio recording in my childhood,” he says. “From age nine to sixteen, I studied with Shizue Yamashiro at her studio near L.A. High School. As I was growing up, she would often talk about Mike Kanemitsu, who was teaching at Otis College of Art and Design. If I wanted to become an artist, she would say, I should consider going to Otis, which I ended up doing. When I was in middle school, I started studying drumming at a drum store in Hollywood. A family friend, who was a professional pianist and composer, heard about my interest in jazz and ended up meeting me at my family’s restaurant on Olympic, to talk about music. His name was Horace Tapscott and he introduced me to audio recording. When I went to Otis, I realized I could combine these three interests; visual arts, music and audio recording. I also had a teacher, Carl Stone, who introduced us to all of these avant-garde composers. It was at Otis that a small group of us started Collage Ensemble, which would go on to be a nonprofit arts collective for 25 years. It was with these artists that I cultivated my artistic vocabulary, collaborative methodology and interest in working with communities.”

“If you see my work today, you”ll notice a kind of collage of various disciplines,” he adds.

But through sound, says Nakagawa, art can engage a person’s memory in ways that other kinds of art might not. “That memory includes sound memory and body memory. We hear with our bodies.”

Nakagawa appreciates the range of reactions that his work elicits. “I’ve met some folks who say they heard a bomb in the Hiroshima/Wendover piece. There are dynamics in the recording that could be taken as something explosive but there were no bombs when I was recording. The important thing is that they heard something that affected them. This is no less ‘true’ than anything else. I see that as a totally legitimate interpretation. I think interpreting is a key participation of an art viewer—and making something that can solicit multiple interpretations is a key function of an artist.”

Alan Nakagawa’s Peace Resonance: Hiroshima/Wendover, 2018 sound art piece is being presented as part of the Japanese American National Museum’s exhibition, Under a Mushroom Cloud: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Atomic Bomb. At JANM’s Upper Level Members’ & VIP Reception to celebrate the opening of the exhibition on November 8, 2019, Nakagawa presented an excerpt. Reception guests were given balloons to hold so that they could experience the sound vibrations in a tangible way.

* * * * *

Under a Mushroom Cloud: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Atomic Bomb is on view at the Japanese American National Museum, November 9, 2019 – June 7, 2020.

© 2019 Darryl Mori / Japanese American National Museum