Irwin's children were biracial in Japan, highly unusual at the time. They didn't feel completely Japanese in Japan nor completely American in America. They faced both identity issues and racial prejudice. Most still opted to live in Japan permanently.

* * * * *

International marriage and biracial children

Despite much privilege and wealth, Irwin and Iki’s personal lives and marriage had many ups and downs. Iki didn't like her husband's drinking and womanizing with geisha, a habit he apparently picked up from his association with high-powered Japanese friends. She resented having to do all the work raising their children, managing three homes (Tokyo homes in Kojimachi and Tamagawa and a summer villa in Ikaho, Gunma), and managing their many servants.

Their first daughter, Sophia Arabella ("Bella"), consoled her mother with Christianity, and Iki realized how tough it must be for her husband to be living in a foreign land. Despite Irwin speaking only broken Japanese and Iki speaking broken English, their historic international marriage lasted, and Irwin was devoted to his wife and children.

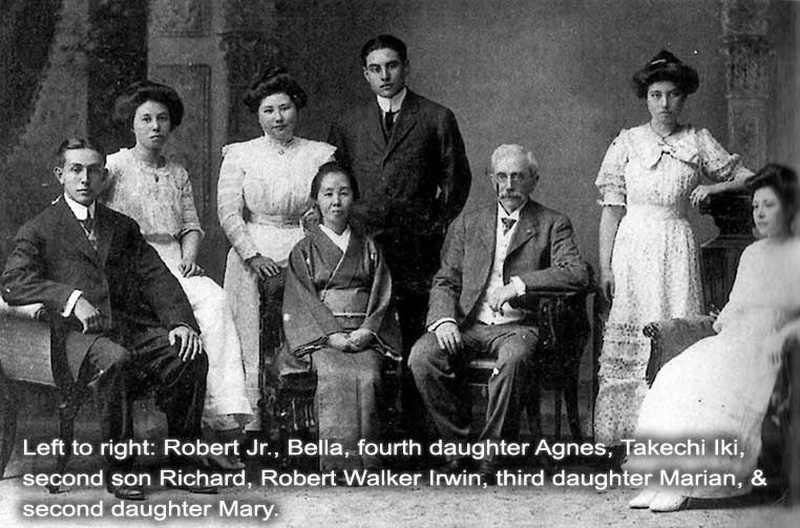

Irwin and Iki had four daughters (Sophia Arabella, Marian, Mary, and Agnes) and two sons (Robert Walker Jr. and Richard), all born in Japan in the 1880s–90s. They were among the earliest (if not the earliest) biracial Japanese-American children in Japan. They all had English names and attended private schools both in Japan (up to primary school) and in the United States (through university). However, the stories of such children in Japan are usually not included in the Japanese-American experience, which generally focus on Japanese immigrants and their descendants in America.

As in the United States, racial discrimination was prevalent in Japan before and during World War II. Many Japanese regarded half-Japanese children as "impure." Eldest daughter Bella (1883–1957) had a bitter experience with prejudice while she was studying in Philadelphia in her late teens. One Japanese suitor, from a highly respectable family, took a liking to Bella and the feeling was mutual. However, the young man's family would not accept her and he was forced to give up his suit. Bella never married.

Because there were very few of them, biracial children of that period faced a unique set of challenges, and the Irwin children had to contend with identity issues as well. In Japan, they did not feel completely Japanese, and in America, they did not feel completely American either. They seemed to have favored Japan, however, since most of the children opted to live in Japan. And those who married usually married a native Japanese.

In 1891, Irwin purchased a summer villa in Ikaho, Gunma Prefecture to escape Tokyo's hot summers. The Irwin family enjoyed the hot spring town's cool climate on the slope of Mt. Haruna every summer. Irwin's spacious villa, on about 300 sq. meters of land near the bottom of the Ikaho Stone Steps (main drag for pedestrians), also served as the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi's secondary legation and was used by his Tokyo staff and guests from Hawaiʻi. (A small part of the villa is preserved on the original site and open to the public. See below.)

Bella loved Ikaho and was popular with the local children. She eventually invited them to the summer villa where she showed them picture books from abroad and offered them sweets. By 1904, her casual gatherings had morphed into Christian Sunday School at the summer villa. She had found her passion in life and went to study preschool education in Philadelphia in 1906 under the supervision of her Aunt Agnes (founder of the Agnes Irwin School in 1869 in Philadelphia) and Aunt Sophia, who were both educators.

In 1914, she studied under Maria Montessori in Rome, Italy and did research on Froebel gifts (educational toys for young children designed by German educator Friedrich Fröbel who also invented the word "kindergarten") at Pestalozzi-Fröbel-Haus in Germany. She returned to Japan and used her own assets to found the Gyokusei Preschool Teacher Training School and Gyokusei Kindergarten in Kojimachi, Tokyo in 1916. Bella was the school's first principal and teacher of the first class of eleven preschool teacher trainees and ten kindergarteners.

Another prominent child of Robert Walker Irwin and Iki Irwin was their third daughter, Dr. Marian Irwin Osterhout (1888–1973), who graduated from Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania and went on to receive a PhD degree in biology from Radcliffe College. In 1933, she married pioneering botanist Dr. Winthrop John Van Leuven Osterhout (1871–1964) and worked with him on scientific research projects. They were long associated with Rockefeller University and the Marine Biological Laboratory. They specialized in cell permeability. She was Irwin's only child to live permanently in the United States and died in New York at age 84.

Meanwhile, brothers Robert Walker Jr. (1887–1971) and Richard (1890–1928) attended Princeton University. Richard also attended Harvard Law School and became a lawyer and executive at Standard Oil Company's Far East branch in Japan. Both brothers eventually married Japanese women. Robert Jr. worked for the Taiwan Sugar Company before the war and settled in Tokyo. With his second wife Tsuneko, he had two sons in the 1920s, John (1926-2016) and Charles (1928-2018). Richard had a son, Takeo (1922-1946), and a daughter, Yukiko (1925-2014). Irwin lived long enough to meet only one of his grandchildren, Takeo.

© 2020 Philbert Ono