Successfully negotiated by Irwin and his close friend Inouye Kaoru, Japan's Foreign Minister, Kanyaku Imin was a government-contract immigration program that started the mass immigration of Japanese to Hawaiʻi from 1885.

* * * * *

Kanyaku Imin Immigration

Irwin’s place in Hawaiian history started in 1880 when his friend Harlan P. Lillibridge resigned as the Kingdom of Hawai‘i’s Consul General in Japan and recommended Irwin to take his place. As Hawai‘i’s interim Consul General in Japan, Irwin’s job was not that busy until he started preparing for Hawaiian King David Kalakaua’s tour of Japan scheduled for March 4th–22nd, 1881. The Japanese government was informed of the royal visit only two weeks before Kalakaua’s scheduled arrival. Kalakaua (1836–1891) originally planned to travel to Japan incognito as ‘Alii Kalakaua” instead of “King Kalakaua,” but the Japanese Consul General in San Francisco, where Kalakaua stopped over on his way to Japan, telegraphed the news to the Foreign Affairs Department in Japan. Kalakaua would become the first foreign head of state to visit Japan.

When Kalakaua arrived at Yokohama Port on the morning of March 4, 1881 aboard the RMS Oceanic, he received a 21-gun salute numerous times as his ship passed foreign and Japanese warships. He was a state guest of Japan as “King Kalakaua” and lavishly feted by Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) and Japanese officials. After spending the night in Yokohama, he and his entourage traveled on a train decorated with Hawaiian and Japanese flags from Yokohama Station to Shimbashi Station. In Tokyo, he met Emperor Meiji and the Empress at Akasaka Palace, and their interpreter was Inouye Kaoru’s daughter (probably the one who had traveled to the U.S. and Europe in 1876–78). Kalakaua stayed at the Enryokan State Guesthouse for foreign dignitaries within the Hama Rikyu Detached Palace (now Hama Rikyu Gardens).

While in Tokyo, Kalakaua toured factories and schools and met with numerous Imperial family members and government officials. The subject of immigration was also brought up. Kalakaua explained that the Hawaiian Kingdom wanted to increase its population by inviting immigrants from other countries to come to the islands, and that any Japanese who desired to settle in Hawai‘i would be permitted to do so. The immediate response was not positive. The Foreign Ministry already had its hands full trying to revise the unequal treaties signed with the Western powers in the 1850s–1860s.

During a private meeting with Emperor Meiji, Kalakaua also famously proposed to have his beloved niece Princess Kaʻiulani (then age 5) eventually marry Prince Higashifushimi Yorihito (age 13), to reinforce the Japan-Hawai‘i alliance. The king had been impressed upon meeting the young Japanese prince, but the prince politely declined, explaining that he was already betrothed to another girl.

On March 15, 1881, Kalakaua promoted 37-year-old Irwin to Hawaiian Minister to Japan in the presence of Imperial family members and high-ranking government officials at a luncheon at the Enryokan State Guesthouse. He was duly impressed with Irwin’s impeccable preparation for his royal stay in Japan, strong business and government ties, family background, and good nature. A week later, Kalakaua left Japan via Nagasaki to continue his nine-month world tour.

Meanwhile, Hawai‘i continued its plea for laborer immigrants from Japan. In March 1883, Irwin was appointed Special Commissioner for Japanese immigration and continued immigration negotiations with Japan. Finally, a major breakthrough came in April 1884, after native Hawaiian Colonel Curtis Piehi Iaukea was sent to Japan as envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary. Iaukea met with Irwin, Foreign Minister Inouye, and, exceptionally, the emperor. He stated Hawai‘i’s proposed terms and conditions for immigration. Although Inouye declined to conclude an immigration treaty at that time, he told Iaukea that Japan would not block immigration to Hawai‘i. This tacit approval finally put Hawai‘i’s Japanese immigration plans in motion.

On January 27, 1885, the first group of 943 Japanese immigrants, under the Kanyaku Imin program for government-contract immigrant workers, departed Yokohama and arrived in Honolulu on February 8, 1885 aboard the Pacific Mail Steamship City of Tokio. They were 676 men, 159 women, and 108 children whose passage and board had been paid by the Hawaiian government. Their monthly wage was to be nine dollars for the men and six dollars for the women, along with a food allowance, free housing, and free medical care. They were to work 10 hours a day and 26 days per month under a three-year contract with the Hawaiian government.

Irwin accompanied this first group of Japanese and also took his wife Iki and 14-month-old daughter Bella. (Iki got very seasick and declined to travel overseas after that. It was her first and only overseas trip.) Irwin did all he could to make the Japanese immigration a success. He sought to educate Hawaiian officials and sugar plantation agents and owners about the Japanese immigrants and made useful lists of suggestions for managing the Japanese laborers. In Japan, he kept the Japanese government informed about the situation in Hawai‘i. Unfortunately, some plantation owners were still excessively harsh on the immigrants, prompting some of the laborers to quit working within a month.

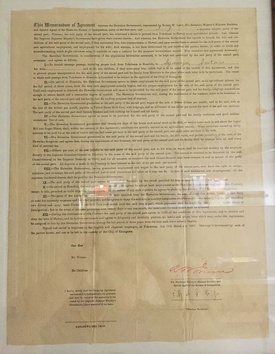

After the second shipload of immigrants had arrived and settled in Hawai‘i, and Japan was confident that its citizens in Hawai‘i would be treated fairly, a formal immigration treaty between Japan and Hawaiʻi was finally signed in Tokyo on January 28, 1886. The treaty was signed by three close friends: Japanese Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi, Japanese Foreign Affairs Minister Inouye Kaoru, and Special Agent and Special Commissioner of Hawai‘i’s Board of Immigration Robert Walker Irwin. The official seal of Emperor Meiji was also imprinted on the treaty document. The treaty stipulated that all Japanese immigrants would go to Hawai‘i under a contract not exceeding three years, signed in Yokohama by the Special Agent of Hawai‘i’s Board of Immigration (Irwin) and the immigrant concerned, and approved by the Governor of Kanagawa Prefecture.

Carrying with him the immigration treaty for ratification by the Hawaiian government, Irwin traveled with the third shipload of Japanese immigrants that arrived in Honolulu on February 14, 1886. The Kanyaku Imin program lasted from February 8, 1885 to June 27, 1894. Although there were several interruptions in the program resulting from arguments between the two governments about terms and conditions, a total of 26 shiploads of immigrants brought approximately 29,000 Japanese men, women, and children during this period. For Irwin, it was a lucrative venture, as he reportedly received a five-dollar commission for each adult male immigrant he recruited. The Kanyaku Imin program was soon superseded and surpassed by Japanese emigration conducted by the private sector until 1924, bringing over 200,000 Japanese immigrants to Hawai‘i.

After the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in January 1893, the Republic of Hawai‘i’s President, Sanford B. Dole, appointed Irwin as the Republic of Hawai‘i’s Minister Resident in Japan on February 25, 1893. In December 1893, Irwin visited Honolulu for a few months and by happenstance met his half-brother John Irwin, Rear Admiral in the U.S. Navy. John was in command of the U.S. Navy ships sent to Honolulu when the U.S. tried to force Hawai‘i’s Provisional Government to restore the overthrown Hawaiian Kingdom. Irwin stayed aboard his brother’s flagship, the USS Philadelphia, named after his hometown. The Japanese cruiser Naniwa, commanded by Togo Heihachiro (famous as the commander of the Japanese Navy in the Russo-Japanese War), was also on hand to protect Japanese citizens in Hawai‘i.

Hawai‘i became a U.S. territory in 1898, and Irwin’s official governmental ties to Hawai‘i ended amicably in 1900. Irwin then focused on producing sugar in Taiwan (then part of the Japanese Empire). He helped Masuda Takashi, Inouye Kaoru, and Shibusawa Eiichi establish the Taiwan Sugar Company (later merged into Mitsui Sugar Co.), with Irwin as an advisor. Irwin had thought of Taiwan as having a similar climate as Hawaiʻi, suitable for growing sugar cane.

© 2020 Philbert Ono