My family roots are in the British Isles, but one name in my family tree stands out: Jujiro Takenuchi. My grandma, Elizabeth Taylor—no, not the famous actress—came from a large family in Chobham, Surrey, England. Chobham is a farming community southwest of London. Grandma had many sisters, one of whom was Annie Taylor, born in 1876.

Annie came to Stonewall, Manitoba, in May 1907 with her husband, Walter Morris Oakford, and their three young children. Within three weeks of their arrival, Walter was dead! He had contracted scarlet fever on the boat. Now what was Annie to do? She was six months pregnant with their fourth child and had only one sister, Fannie, and her husband, George Sloan, to help her. The little girl was born in August 1907, and Annie had to work to support her family. She had an agonizing decision to make. How could she work with a newborn baby? A nearby family desperately wanted a child, so Annie allowed them to adopt her baby. Annie found work as a housekeeper with James Tenning, a Japanese farmer who was a widower. Now I have your attention, don’t I? You are saying, “That’s not a Japanese name.” You are right!

So who was James Tenning and what was his story? James was born Jujiro Takenuchi on November 28, 1868, in Kuwana-gun, Mie Ken, Japan, to Heirjiro Takeuchi (Takenouchi) and Seki Kurosa. He was from a samurai family. He grew to five feet seven inches, tall for a Japanese. In 1888, after he had lost his father and then his mother, he entered a navy accounting school where he graduated as the top student in 1891. He was given a dirk from the Emperor and worked on battleships for the Japanese Navy for the next few years.

In 1898 Lieutenant Commander Takeuchi was sent to London, England, as an accounting manager for the purchase of three naval warships. In 1902 a terrible discrepancy was discovered. Jujiro and his colleague, Kanzaburo Kagi, a navy commander, had swindled a total of 330,000 yen of the money intended for building the warships. In today’s value that is $7,540,965 Cdn! Jujiro and Kanzaburo had sent much of the money to Ryozo Nagura, a senior naval colleague in Japan. Ryozo eventually returned part of the money but committed suicide before disclosing his part in the theft. Despite Ryozo’s involvement, he was found not guilty by the navy court. Kanzaburo received a much lighter sentence than Jujiro, who was sentenced to 10 years' strict imprisonment in absentia.

Jujiro married an English woman named Sarah in England, and on November 25, 1904, he arrived in Halifax on the ship Bavarian as a married farmer going to Winnipeg, Manitoba. Land was cheap then and many people were coming to homestead in the prairies. Jujiro’s farm was just outside of Stonewall in an area called Grassmere. Sadly, Sarah died soon after of a burst appendix, and Annie Taylor came into his life as his housekeeper.

On February 26, 1908, James Tenning and Annie Taylor were married in Stonewall, Manitoba. Were they in love or was it a marriage of circumstance? I was told that Annie’s family was very upset that their daughter was marrying a Japanese gentleman and refused to speak to her. I’m sure that if Jujiro’s parents were still alive they would have thought he was marrying beneath his station.

Now Jujiro had three children from his wife’s first marriage: Walter, age six; William (“Hap” for Happy), age four; and Dorothy, age two. In 1909 Annie and James had their first child together, Stanley Juan Tenning. Soon another son, Robert Jusan, was born, and five daughters followed: Amy Rosalie, Elsie, Winnifred Sarah, Margaret Elizabeth, and Evelyn Grace.

My uncle, Dick Hunter, was Elizabeth Taylor's son and Annie's nephew. Two of Annie's daughters visited Dick in the hospital when he had open heart surgery; he had never met any of his aunt's family before and was thrilled to meet them. Dick said they were gorgeous and very polite. On another occasion, in the 1950s, Dick's wife, Louise, visited Annie and some of her daughters and found Annie to be a very pleasant and a kind host. Over the fireplace were two Japanese swords. The Hunters lived in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. Other Taylors lived in New Zealand, England, and Manitoba.

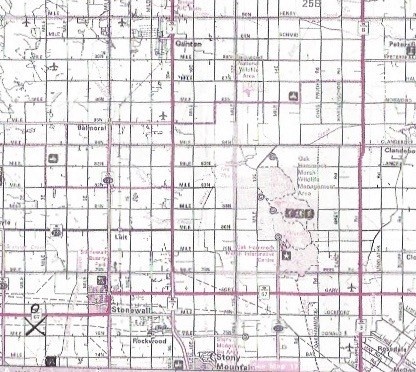

The Tenning farm was on the section of land with the X on it. O marks where the school was located. The black box at the bottom marks the Presbyterian Church. Winnipeg is about 35 kilometres south of Stonewall.

I was told by a relative living in Stonewall that Jujiro was not much of a farmer. In 1917 he lost the farm and went to work in Saskatchewan for other farmers as a labourer. I doubt that Annie knew his story before she married him; in fact, I wonder when he told her the truth. I’m sure he was not proud of his past and didn’t want to think or talk about it. He was an exile from his homeland, his family, and his friends. He was not trained to be a farmer and preferred painting and writing poetry and songs, and was, of course, good with mathematics and accounting.

William Taylor1 of Stonewall remembers his uncle James Tenning visiting his family and that he always had candy in his pocket for William and his sisters. William and one sister still live in Stonewall. He is 105 years old! His father was Harry Taylor, Annie’s youngest brother.

Jujiro’s son, Robert Tenning, described his mother as a strong person who had a hard life raising her family. Robert said that his father never scolded his children; instead, Annie did that.

He also said that Jujiro was good at judo and taught the children how to perform the martial art. As well, Jujiro taught them how to play poker and how to write letters in Japanese using pen and brush. He would build kites in Stonewall and fly them.

At the same time, Robert said, his father rarely showed affection to his children. Robert wrote of his early life: ”He never spoke to us about what he did before he came to Canada. Father used to take the buggy out with the two horses and whenever he met a lady on the road he would raise his cap like an English gentleman. I lived a lonely life as a boy. I never had any friends. We never had much of a family life. I used to go out into the woods and look at the birds. I was alone a lot. From 14 to 15 I started to work. I have no good memories of family life in Vancouver. We seemed to go our separate ways. As you get older you rely more on your family but I didn’t have that kind of relationship with my sisters and I think they felt the same way.”

In 1928, Tenning went by himself to Vancouver to work at the Tairiku Nippo newspaper; according to Robert, Annie did not want to leave Stonewall. The following year Robert and Stanley joined him, and the next year, 1930, Annie and the girls came to Vancouver.

Robert wrote that in Vancouver his father became a different man. He worked hard for the Japanese community but neglected his family and began to drink constantly. Jujiro wanted to return to Japan, to the beautiful cherry blossoms and the small stream he used to fish in as a boy, but he could not and the sake helped drown his sorrows.

In Vancouver Jujiro worked first for the Japanese newspaper, then became a translator for the Japanese Fishing Association in Steveston and later a secretary for them. His last years were spent drinking. He was sent to Essondale Hospital, where he spoke only his native tongue. He died there of chronic myocarditis and arteriosclerosis.

On his deathbed, James Tenning made a final request of his son Stanley. He said, “Cast my ashes into the ocean at Steveston and I will finally return to my home in Japan.” Part of his ashes were returned to Japan and his grave can be found at Hosei-ji temple in Kayuchi.

I think both Annie and Jujiro went through difficult times. The little girl Alice whom Annie gave up for adoption did not have a good life. She lost her adoptive mother at age 13, married twice, and had one daughter, and yet she attended Annie’s funeral, so she must have known her mom in later life. Annie and Jujiro came from different cultures and religions, and I’m sure that affected their relationship. I wonder about Annie’s three older children and how they got along with their half-brothers and -sisters. What became of their lives?

When I talked to some of Jujiro's descendants on the phone they were reluctant to talk to me because of the circumstances of Jujiro’s exile. I do not judge. Jujiro said that he took the money to help other officers who had got themselves into trouble with gambling, the stock market, and women. One was threatening to kill himself. What would I have done in a similar situation?

It is clear that the children suffered and that Jujiro was very homesick. Annie was isolated from her family and bore the brunt of raising the children. In Vancouver her husband distanced himself and drank too much.

Annie and Jujiro were my great-aunt and -uncle on my father’s side of the family. There is tragedy in this story but there is happiness in the grandchildren and great-grandchildren. One of Annie and Jujiro's granddaughters received a national teaching award in British Columbia. It is time to move forward. I would like to meet some descendants of their family one day.

Note:

1. William Taylor was alive when this story was originally written, but he passed away in August 2017 at 105 years old.

*This article was originally published in Nikkei Images (Vol 23, No.1).

© 2018 Judy Hunter Teague