My mother died on December 21, 1976. That Christmas was numbing. We already had the tree and gifts for my niece, but we took down the decorations. My niece was only three so it was ok with her. These days I look forward to Christmas and the whole commercial shebang. The lights, the carols, the brightly wrapped packages—all of it starting from Macy’s Christmas parade on Thanksgiving morning on TV. Some consider it crass, but I know from the Christmas when my mother died, it is the human spirit enduring the long, cold winter that is only just beginning on the darkest day of the Northern Hemisphere.

Since then, my brother, his family, and I get together every Christmas from Christmas Eve to toasting in the New Year. Although we no longer go to temple regularly, we also gather together for a Buddhist service in memory of my mother. We don’t talk much about her, but we remember and comment on what we think she would notice about service, about Christmas, the gifts we exchange. Sometimes I think because she died around Christmas time, the season’s rituals have kept us close despite living in different states.

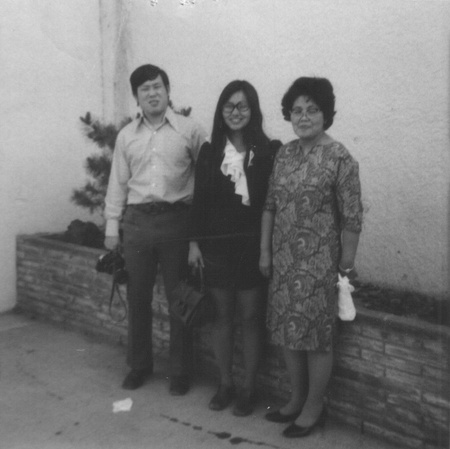

After my father died, we moved from Los Angeles to live in Eastern Oregon with my grandfather. The mayor of the town, Ontario, had invited Nikkei to come to help clear the land for farming during World War II. After the war, many like my grandfather settled there rather than return to West Coast homes. My mother worked in the fields in the summer and in the cannery and packing shed in the winter. There she took the swing or night shift so she could take care of us during the day. Once I woke up to see her scrubbing the floor at 3:00 AM after she returned from the cannery. She went to school to become a beautician and hated it. But it was a good winter job. Even weeding onions paid more in the summer. Finally at 50 when my brother was living in Japan and I started teaching in Oakland, she went to nursing school in Idaho – her life long dream.

I asked her why she joined the local chorus to sing the Messiah at Christmas time. We were Buddhist after all. She said my dad liked to sing the Messiah so encouraged by one of her hakujin beauty salon clients she decided to try it. Once I asked how she kept going never complaining, never stopping. She didn’t answer me just looked as if I had asked a foolish question that she didn’t understand.

But I did learn how.

She was in the hospital supposedly recovering from an operation for stomach cancer. Only the guts of the operation didn’t happen. “Too late,” the doctor told me. When he opened her up, the cancer had spread too far, and he couldn’t go ahead and remove the tumor. My mother must have known this. The moment she was conscious, despite the long cut on her abdomen, she was kneading the lump in her stomach with familiarity. The doctor didn’t come after she regained consciousness to examine her or talk with her. She looked at me, and I told her.

Not saying anything would have been useless. Back then in 1976 some people did not believe in telling people they had a fatal illness, but my mother was a nurse, and 30 years earlier she had nursed her own mother dying of stomach cancer in the hospital at the Heart Mountain Concentration Camp. My mother’s hospital was not behind barbed wire. She even had a bedside phone to talk her brother in Chicago, and I was there from California. She was in Caldwell, Idaho, which was only 30 miles from Ontario, but not as welcoming.

Looking back I can’t help, but wonder if her hospital care was neglected because she was Japanese American. Even then, I thought her doctor was callous. She didn’t officially die of cancer, but choked in the middle of the night after they removed the tube draining the fluids from her stomach. During day she kept vomiting, but felt better by evening. She wanted to crochet the pillowcase that I was embroidering. We took turns working on the case and finished it. That night she died.

Death is death. No amount of speculation or brow beating can bring someone back to life.

Back in her apartment, I found hints on how she had pulled herself together and hung on to hope even though she saw her mother die of the same disease. The passages on stomach cancer in her medical book were heavily marked—describing the illness in detail. To my surprise it promised the possibility of recovery with early diagnosis. This was a change from the family story of inevitable death from stomach cancer which had haunted generations of women in my family. She had taken out a loan to tide her through the long days of recovery after the operation. She had marked and labeled all her legal papers (health insurance, will, bank accounts) and filed them in a wooden tomato crate. Left on the piano as if she just finished playing was my father’s sheet music.

Practicality was her stepping-stone through her life—life after camp, widowed at 35 with two small kids. I thought about how we moved into Grandpa’s two-room house that was barely a shelter against the harsh weather of a high desert. In the spring she planted a lawn. She didn’t stop. I saw she had marked passages in Buddhist readings and scriptures and copied them in a spiral notebook. Buddhism was her shield against a difficult existence. The obutsudan, the Buddhist shrine, was on the bookcase next to her bed. She must have slept every night with the Buddha looking over her.

© 2018 Grace Morizawa