[To Digger] I think it’d be interesting to talk about your first impression of Tule Lake and arriving.

Digger Sasaki (DS): Being in Pinedale for three months, it gave me a little awareness of barracks and stuff. But Pinedale was so small in comparison. And the reason they sent us to Pinedale is Tule Lake wasn’t finished as far as building all the barracks. To tell you the truth, I couldn’t remember how we got to Tule Lake from Pinedale. I haven’t even thought about that, because that’s a long distance.

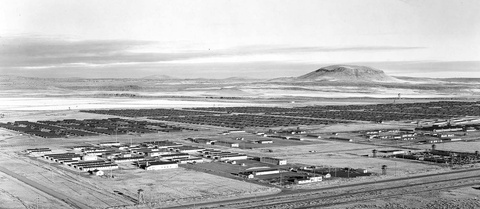

I was really impressed with so many barracks. Eventually I found out that that was the largest of all the concentration camps. I think they had approximately 10,000 people there. I was impressed with the size of the place. All the guards, real tall fences, you know. And all the guard towers.

Was that frightening to you at all?

DS: You know, it must’ve been because of my age that I didn’t feel frightened or anything but everything was, a different world. I don’t remember being scared. Yeah I was impressed with how large it was. And two landmarks, Castle Rock and Abalone Mountain.

Were a lot of your friends there in Tule Lake?

DS: It seemed like Auburn people were kind of in the same ward. There were six wards together and we’re in Block 49, like your grandparents. Let’s see. In our ward, there were a lot of the Auburn people but come to think of it, I just had a very few friends in that ward.

Well, this is before the segregation. I didn’t have a real close friend. We would just play sports and just to keep busy I guess, sports was our main outlet or activity. And played basketball, baseball, and football without pads. And we tackled, you know. Then we had the segregation, you know about that right?

The no/no segregation?

DS: That questionnaire. Number 27 and 28. Some people went from Tule to another camp. Because they went yes/yes. So they sent them to other camps.

Agnes Sasaki (AS): But your dad could’ve gone to another camp but he didn’t want to move again. Because Pinedale was the first move.

But did he believe in what he was saying no/no to?

DS: I think he had his loyalty to America, yeah. I guess just staying there felt more secure for him instead of moving someplace else. That’s the way a lot of the Isseis are, I think. They don’t want to venture out that much.

AS: [To Digger] Was he ever given the option of going back to Japan?

DS: No.

And they wanted to stay in the U.S. right? Was the goal to move back to Washington?

DS: I’m really not sure about that. I guess he would’ve moved back to Washington if anything. That’s the way Isseis were, they aren’t like the Niseis. They’re kind of settled in their own way, you know. Don’t want to try different things.

Do you remember observing any of that conflict in Tule Lake between the Isseis and the Niseis? Or seeing arguments?

DS: Oh yeah. I saw some fights and stuff between loyal and disloyal people. And there was a group of some I guess you call them Kibeis, those loyal Kibeis used to go to certain barracks and pull the occupants out and all fight them and stuff like that. I remember actually seeing that.

And they were how old?

DS: I would say early to mid-twenties.

And they would target people who said that they were loyal to the U.S.?

DS: Yeah. Or they felt like they were spying on the disloyal people and stuff. I saw that incident and in fact I still know the person’s name but I won’t say the name or anything.

AS: So another name for the disloyal were the no/no?

DS: Yeah. You couldn’t really say disloyal, because some of them objected just because their rights were taken away. Well the government shouldn’t put out a question like that anyway, you know. That’s for woman and men. If you’re at another camp and you said no/no, you went to Tule Lake. The question was for everybody.

It wasn’t the smartest thing but it was also brilliant, to keep all the resistors together. Did you see mainly Kibeis doing that to the “loyals” or was it a group of all different people?

DS: Yeah, the group that I knew of, was a complete mixture. There was a lot of people accusing different people for ratting on them. It wasn’t a good atmosphere in the camp because of that. That was before the segregation took place.

Did you see that mentality trickle down to the teenagers and younger kids or was it mostly just adults?

DS: I think it was basically just adults, yeah. But once the segregation took place, even myself, we ended up having to go to Japanese school. Instead of English school. It was funny because some of the little kids knew more Japanese than we did. But we were towering over them.

So were you in the school where they had to wear the hachimakis?

DS: No I don’t remember how we ended up in that group. Maybe just to be active, I guess. In fact my friend [Ken Harada] and I, since everybody else were going, we joined it. Wore our headbands and we used to run around the camp. When you run, they used to say “wasshoi, wasshoi,” so we were called the “Wasshoi Group.”

But after the segregation, my friend and I joined a so-called gang. Because you kind of had to protect yourself so they had other gangs within the camp. We used to make knives and things.

How many people were in this gang?

DS: In our gang there were about eight. Ken and I everyday just stuck together. They moved in from Topaz to Tule Lake and they lived in the next barrack.

So this gang was more just to have protection?

DS: Fortunately the other gangs, somebody knew somebody from the other gangs. So we didn’t end up getting into a big fight.

And these were all groups of teenagers?

DS: I was only about 14. In fact before the segregation, I lied about my age and got a job at the warehouse and then there were two older fellows, we were all in a truck and made deliveries throughout the camp.

So looking back at it now, you never saw camp in a bad or traumatic experience, did you?

DS: Not really. Another funny story is before segregation, there was a four of us that we were able to go out of camp to this Abalone Mountain. We’d go hunting for rattlesnakes and we’d get on the big rocks with the wire, we’d drag the rattlesnakes down and then we’d tie it noose-like, the snake, and put it into a jar. Then we’d sell it to an old person in camp. Then when we’d go see him, it’s in a jar, like it’s pickled or something. I don’t know what he does with it. He’d use it for medicine purpose. One time we had a jar, I think we had two jars, and we were coming back to camp and this younger boy accidentally hit the rock with the jar and it broke and the snake got out.

What was your favorite memory with your best friend in camp, Ken?

DS: Well when you look back, that gang thing was funny.

AS: Because it wasn’t a real gang.

DS: Well it was a real gang! Kenny and I, we were involved in a lot of sports. Baseball, softball, football, basketball. Majority was basketball. The courts were all just dirt. And then we built our own baskets, the supports, and stuff. Yeah our gang, we called it “hachimaru,” hachi is eight and maru is round, so it’s for “eight ball.”

That’s clever.

DS: We used to have jackets, the warehouse people used to wear. Denim. And somebody put it on our back, “hachimaru,” eight ball.

You don’t still have that, do you?

DS: [Laughs] No, I wish. But I remember when they had all these fights and riots, they had a curfew after. And Kenny and myself, we used to meet at a certain barrack, for gang activities. And then once the curfew came, after seven o’clock or so, you’re not supposed to be outside. But Kenny and I, they used to have jeeps that patrolled all over. Kenny and I, we would go to the gang thing I guess past the curfew, so we’re dodging the jeeps. Getting home. It used to be kind of fun. Yeah they had soldiers and jeeps with machine guns, you know, patrolling the camps. It was kind of exciting in a way.

*This artice was originally published on Tessaku on October 16, 2016.

© 2016 Emiko Tsuchida