During the cooler months of fall in the Imperial Valley before the war, only one thing was as important, if not more important, than the price of lettuce—high school football. It was a time when football was not relegated to the sports page of local newspapers. Football news was front-page news and the names that appeared on the front page were names like SASAKI and KITA.

It was a different time, indeed. In those days when football was king, a strong sense of Nikkei community also figured large in the Imperial Valley. Isamu “Sam” Nakamura once reminisced fondly about going to football games with a bunch of his Nisei pals at the Brawley high school athletic field across the street from the Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church. The star players on the field were Japanese Americans like themselves. When the game was over, and the Friday night lights were dimmed, the boys would walk through the chilly air to Nihonmachi (Japantown). At Fat’s Café, owned by the Kuramoto family, they ordered hamburgers or a hot bowl of udon. As they ate, they reported to Mr. and Mrs. Kuramoto on how their son, Eichi, played in the game that night.

Throughout the Imperial Valley, a remarkable number of Nisei played football and even excelled in the sport. This was a local phenomenon. In most rural areas Nisei boys were resigned to believing that they were too small in stature to be competitive. In her book Farming the Home Place (1993), Valerie Matsumoto explains that in the San Joaquin Valley, they participated in baseball and track, but “their relatively smaller size prevented them from playing first-string football.” Such was not the case in the Imperial Valley where hardy Nisei boys were passionate about the game. They were no bigger than their counterparts in other areas; they just played bigger than their size.

George Kita, possibly the best football player Calexico high school had ever seen, was described in the Calexico Chronicle as “a small man for the guard position,” but that he “makes up for his lack of weight by smart and aggressive playing.” Central Union High School’s center, 120-pound Noboru Myose, drew large crowds to games in 1939. Nobody believed that he could play the position so they had to see it for themselves. One of his white classmates recalled that “everyone marveled at how such a light fellow could snap the ball then take out one of the opposing players. It was sheer determination.”

By demonstrating their grit, local Nisei football players not only earned the respect of their fellow teammates but also the adulation of the whole community. As a consequence, in an environment where churches and Boy Scout troops were segregated, racial tensions may have abated to some extent. Mitsuo Henry “Hank” Sasaki, arguably Brawley’s greatest gridiron legend of the prewar era, put it this way, “It helped quiet down the racism because football is so big.” But Hank rejected the notion that the sole motivation of the Nisei to play so doggedly was to ameliorate the discrimination. He declared emphatically, “We played for the pure enjoyment of the game!”

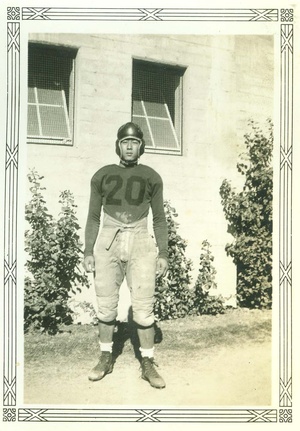

A 1936 graduate of Brawley Union High School, Hank Sasaki played on the Wildcat football team all four years. On October 5, 1935, he scored the winning point during a thrilling game in Brawley against Coronado. His celebrity was clinched when the Brawley News sportswriter, Paul Post, covered the game in his article titled “Henry Sasaki Stands Out as Great Football Star in One of Best Games Ever Seen Here.” Post wrote, “Sasaki virtually ran, passed, and kicked the Brawley team to victory and firmly established himself as one of the best high school backs in Southern California if not the entire country.” What Hank exuded was raw talent. Because of his speed, passing skill, and accurate kicking, rival schools nicknamed him the “Triple Threat.” According to Kiyoshi “Ambrose” Masutani, Hank was so highly regarded—and feared—that when the Wildcats played against the Spartans in El Centro, placards made by a print shop were posted all over town. The professionally-made signs read “Stop Sasaki.”

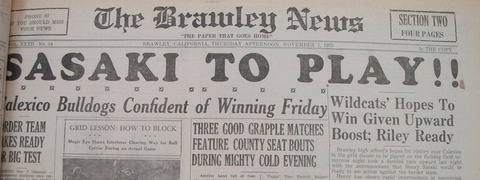

Before a crucial game against Calexico, which led to the Imperial Valley league championship in 1935, Brawley’s Coach Clark debated whether or not to play his leading right guard, Hatsuo Morita, who had severely hurt his arm in a previous game. A special brace had been devised for his arm so that he could be put in if needed, but the coach did not want to risk further injury. The Brawley News warned that the “loss of the chunky guard would be keenly felt by the Wildcats as Morita has been one of the most outstanding linemen of the Brawley High roster this season.” Making matters even worse, Hank came down with the flu. Brawley was mortified by the sports page headline “Henry Sasaki Reported Out of Calexico Game—Wildcats Made Underdogs in Friday’s Contest on Border as Star Still Ill With Flu.” As game day approached, the panic-stricken residents of the north end anxiously awaited any hint of Hank’s condition. The day before the big game, the town received the news that it had prayed for; the front page of the Brawley News blared: SASAKI TO PLAY!!

Upon graduation, Hank earned a football scholarship to the University of Southern California. He was sponsored by USC alumnus Charles Morrow, the owner of the Brawley Lumber Company. “Our Henry” was the first Japanese American to play football at USC; he quarterbacked the Trojan team.

The Brawley News kept locals abreast of Hank’s successes in Los Angeles under such headlines as “Brawley Gridder Popular Among Trojan Mates” and “Sasaki Sets Rapid Pace At USC.” According to one article, the “former Wildcat gridiron star is getting lots of attention from sports writers in Los Angeles who see great possibilities in the stocky Japanese lad’s efforts.”

Athletic prowess seemed to be a genetic trait in the Sasaki family. Hank’s big brother Tom was a gridiron star in his own right. Described as a “flashing end,” Tom was the team captain during his senior year at Brawley High Union School. Under his leadership the Wildcats won the Imperial Valley Championship and then went on to win the Southern California Interscholastic Federation Championship.

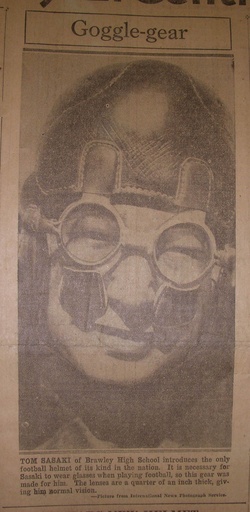

For a time, Tom and Hank’s high school football careers overlapped with Hank as quarterback resulting in the “Sasaki to Sasaki pass.” A peculiar invention designed specifically for the elder Sasaki illustrates the great lengths to which Brawley boosters went to ensure that their win-producing players stayed in the game. Tom’s playing days nearly came to an end when it became evident that he was having trouble seeing the ball.

Described as a football enthusiast, Brawley optometrist R.L. Secord was determined to see Tom utilize his talents and not allow his poor eyesight to be a deterrent. Dr. Secord created a custom-made leather helmet with quarter-inch prescription lenses fitted into it. Tom submitted to having a plaster cast made of his head so that the helmet could be properly shaped. A perfect fit was essential for Tom’s vision to be clear and undistorted. Dr. Secord’s novel “goggle-gear” was unveiled on the front page of the Brawley News on October 27, 1933, and was lauded as “the only football helmet of its kind in the nation.”The south end of the valley had its own football hero in George Kita who graduated from Calexico Union High School in 1938. George began earning accolades as a right guard on the Bulldog team in 1936 when his friend and fellow Nisei “Jumping Joe” Kokubun was the team’s quarterback. At the end of that season, George’s teammates elected him team captain. The decision was announced on the front page of the Calexico Chronicle on December 17, 1936. According to the article titled “George Kita Is To Lead 1937 Grid Squad,” he was the only football player to receive All-Valley Honors by a unanimous vote of the coaches, athletic officials, and sportswriters in the Imperial Valley.

During his final season at Calexico high school, a south-end reporter hailed “captain George Kita” as “easily the outstanding guard of the conference.” Because of his extraordinary command of the game, it was George, rather than the team’s quarterback, who called the plays in the huddle. Even the coach reportedly deferred to George’s judgement. In recapping a 12–0 Bulldog victory over El Centro, the reporter continued, “In addition he directed the play like a veteran, his canny choice of the trick pass resulting in Calexico’s second touchdown.”

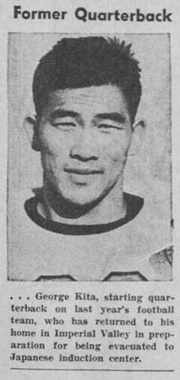

George went to San Diego State College on a football scholarship, and he lettered each year from 1939 to 1941. He was the starting varsity quarterback of the Aztec team when his college education was cut short by Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

In Calexico, George’s parents were arrested by an overzealous police officer who saw them working in their grocery store beyond the 8 p.m. curfew, which had been imposed on all persons of Japanese ancestry. When the Kitas did not return home, their three children worried and got word to their brother in San Diego. George withdrew from San Diego State College to care for his younger brother and sisters and to mind the store in his parents’ absence. He wrote to his Aztec coach, Leo Calland, “As yet there has been no evacuation order for the valley, but it is expected momentarily. It all seems like a horrible nightmare.”

During the war, George was granted special permission to leave the Poston concentration camp to attend law school at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. He played football there as a fullback, and he caught the eyes of many. During the National Football League draft held on April 8, 1945, George was selected by the New York Giants as the 262nd overall draft pick in the 25th round. But the war ended before he had a chance to showcase his gridiron skills at New York’s Polo Grounds. George received a telegram from the Giants informing him that he need not report for tryouts as enough of the team’s regular players would be returning from the service to fill all of the roster spots. Needless to say, George was utterly disappointed. He had graduated from Drake University, and while still under contract with the New York Giants, he decided to accept a job with the Social Security Agency in Baltimore. He subsequently became an attorney and established a successful practice in Chicago.

Along with George Kita, All-Valley Honors were awarded to Akira Aisawa, Shigeru Imamura, and Hatsuo Morita, all of Brawley, and Holtville’s John Masutani. From Brawley, Joe Sase went on to play for the Aggies at UC Davis. Barefooted placekicker Dick Kunishima, of El Centro, played with the Whittier College Poets and later became one of the first Japanese American high school football coaches in Los Angeles County. Additional Nisei football notables were Tom and Joe Kokubun, of Calexico, Brawley’s George Narike, and Kozo Sanbonmatsu from Holtville, among others.

Golden Tornadoes

While few Nisei played football in farming communities outside of the Imperial Valley, Japanese American football leagues did flourish in cities with sizeable ethnic Japanese populations, such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Sacramento. With the desire to compete and a strong belief in themselves, the valley Nisei wanted to test their mettle against the big city teams when the high school season came to an end.

The Brawley Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church sponsored the local team, which called themselves the Golden Tornadoes. The team was comprised almost entirely of Brawley boys, however, a few standout players from other towns were recruited, including George Kita and Joe Kokubun from Calexico, and Yoshio Kashiki and John Masutani from Holtville. Thanks to the good offices of Wildcat coach and science teacher Harry Yochem, the athletic department at Brawley Union High School supplied the Golden Tornadoes with uniforms and gear and permitted the use of its locker room and playing field. George Yamaguchi was the team manager and Tom Sasaki coached the team while he was home from UC Berkeley for winter holidays.

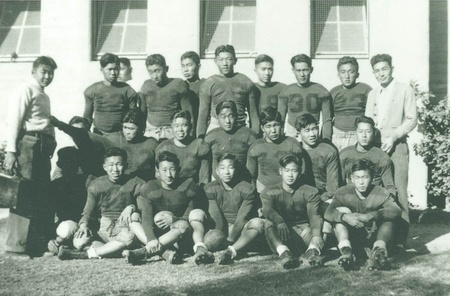

Front row, seated (left to right): Tokio Shiomichi, George Sasaki, Nelson Kitsuse, Roy Sasaki, Morio Ikeda, Tadashi Tokuda.

Middle row, kneeling (left to right): Kiyoshi Fujimoto, Harvey Suzuki, Akira Aisawa, Hatsuo Morita, Toko Taira, George Kita, Takeshi Sato.

Back row, standing (left to right): George Yamaguchi (team manager), Richard Suzuki, Eichi Kuramoto, Shogo Saito, Henry Sasaki, Shigeru Imamura, Yoshio Kashiki, Don Osako, Masaru Fujimoto, Tom Sasaki (coach).

Not pictured: Frank Higa, Kiyoshi Izumi, Joe Kokubun, Jack Maeda, John Masutani, Eichi Nakazono, Hara Otomo, Mitsuo Saito, Toyo Sakamoto, Takeshi Taira. Courtesy of Japanese American Gallery Collection.

Between 1935 and 1937, the Golden Tornadoes played against the Los Angeles Golden Bears, Los Angeles Gakuseikai Anchovies, and a team from Harbor City, as well as northern California teams including the East Bay (Oakland-Alameda) All Stars, and Sacramento Taikus. Interestingly, articles covering important home games appeared in the Brawley News. Some of the headlines were:

- Local, Coast Japanese To Play For Title

- Southern Cal. Japanese Grid Title at Stake Here Sunday

- Henry Sasaki Here to Play with Tornadoes Against Big Nippons S.F. Grid Team

- Northern Pigskin Players Will Meet Stiff Contest With Local Japanese Eleven

On the last Sunday of December in 1935, the Golden Tornadoes took the field against the Los Angeles Gakuseikai Anchovies with the Southern California Championship on the line. The game was played in Brawley on the high school football field amidst strong wind and heavy rain. Despite the bad weather, the whole community—not just the Issei and Nisei—came out to watch the game. They were all made proud as their hometown heroes won the championship title by shutting out their opponents, 13–0. Admission to the game was charged and enough money was raised to purchase new hymn books for the Brawley Japanese M. E. Church. After the game the church’s fujinkai (women’s auxiliary) prepared a dinner in honor of the visiting Los Angeles team.

Following their victory in Brawley, the Golden Tornadoes advanced to the State Championship and defeated the team with the best record representing the Japanese American Athletic Union League of San Francisco. Hatsuo Morita played center on the local Nisei team, and he would never forget the arduous trip to San Francisco. Shogo Saito, who hauled vegetables for the Aisawa & Honda Produce Company, transported the team to the state championship game in his bobtail truck. The entire way from Brawley to San Francisco, the Golden Tornadoes huddled on the open, wooden bed of the truck underneath a canvas tarp. In becoming statewide champions, the inaka (rustic, country) gridiron players showed their true mettle both on and off the field.

When Hatsuo Morita passed away in 1997, six members of the 1936 Brawley Wildcat football team and two Golden Tornadoes served as honorary pallbearers and made a floral presentation during the memorial service. The eulogy was given by the “Triple Threat,” Hank Sasaki. At 98, Hank lives in Los Angeles and he recounts his football exploits using the same colorful language that he uttered when he played the game.

Epilogue

During its annual induction ceremony, the Imperial Valley Football Coaches Association names outstanding former players, exemplary supporters, and coaches to the local Hall of Fame. Typically, each year, one player representing the decade during which he played is selected from every high school and junior college in the county. The following Japanese Americans are Imperial Valley Football Hall of Famers:

Henry Sasaki (Brawley, 1930s)

George Kita (Calexico, 1930s)

Yosh Sanbonmatsu (Holtville, 1940s)

Joe Asamen (Brawley, 1950s)

Dennis Morita (El Centro, 1970s)

Larry Shimamoto, Booster (Imperial, 2013)*

*Lawrence “Larry” Shimamoto did not play football but he was one of the most dedicated boosters of the Imperial High School Tiger football team. Larry was a member of the Imperial Quarterback Club for 26 years and served four terms as club president. In 2004 the Imperial Unified School District honored Larry and another longtime supporter, Eddie Simpson, by naming the high school football field Shimamoto–Simpson Stadium. It is fitting that the first, and thus far only, public facility in Imperial County named for a person of Japanese ancestry, is a football field.

* This article was originally published in Teikoku Heigen News (Winter 2016), a publication of the Japanese American Gallery, Imperial Valley Pioneers Museum.

© 2016 Tim Asamen