On April 2nd, there will be a national “Japanese Canadian Art and Artists Symposium” at the Toronto Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, the last one was in Vancouver in 1996.

The one-day event will feature keynote speeches by two important veteran Canadian Nikkei artists: Vancouver’s Haruko Okano and Grace Eiko Thomson of Winnipeg who now resides in Vancouver.

Organizer Bryce Kanbara says: “The Japanese Canadian (JC) artist community is diverse with established and emerging artists, offspring of mixed marriage who grew up with slim knowledge of the Japanese Canadian experience, as well as new immigrants from Japan who have created another contribution to the Japanese Canadian community and the arts.

“The upcoming symposium will bring together artists and non-artists from the different generations and backgrounds to discuss their experiences and ideas for networking, mentoring, collaboration, and the role art and artists can play in the JC community. Really it's about getting to know one another. A coming together of individual parts to make for a more creative whole.”

* * * * *

You were kind enough to share some of your early history with me. How would you describe yourself as a Canadian Nikkei?

I consider myself to be a cultural hybrid because although I am biologically Japanese and my lineage is Japanese I was raised mainly through the Children’s Aid Society that is based in Ontario. So from the age of 8.5 to the age of 18, I was raised as a foster child by Caucasians.I briefly saw Japanese people who had babysat me while I was with my mother but that was just a short meeting or two. After 18 I did not connect with Japanese people as I lived in Collingwood, Ontario and married a Caucasian so did not see Asians for another seven years.

How do the pieces of your personal history help to shape you as an artist? When did you know that you wanted to devote your life to art?

I have always been creative. My mother was a seamstress and designed and sewed clothing for wealthier women when she was well enough to work. I did not have a lot of toys and I had only the stuffed dolls my mother made for me and fashion magazines that my mother had bought.

What honed my creative problem solving and imagination was the minimum of commercial toys forced me to think creatively in order to occupy me while my mother took care of business. We were extremely poor and lived in one room most of the time I was with her.

What originally drew you into the world of art?

I have always used art as a means of consoling myself. In my first major foster home there was violence, sexual abuse and we were isolated out in the rural country. The environment was very predatory. There was always a sense of being managed but not loved and so I turned to art, mostly starting with drawing and painting. It was just one social worker, Marnie Bruce who I consider the only one to show me genuine respect and care. She was the one who sensed that I needed to go to art school and that perhaps I would have a better chance of surviving and perhaps thriving. In all the 10 years as a permanent ward of the Children’s Aid Society, Miss Bruce was the only one who truly demonstrated, beyond her job, as a person who actually cared about me as a person.

Can you describe your personal philosophy and work as it is now in some detail? How do you express your “Nikkeiness”? How can someone for whom their experience of being biologically Japanese but culturally western express their Japaneseness?

I came back to Vancouver drawn by this one memory - I am in the basement of the Buddhist church on Powell Street. It’s Japanese Sunday school and a young man is encouraging the children to pour water over the head of this statue of Buddha. I can hear adults chanting upstairs and I am afraid to pour the water on the Buddha but the young man encourages me saying that it is okay and it is good.

To be born in a time of hatred of Japanese in a country that used its political power to disenfranchise Japanese people who were born Canadian means you can truly never be part of this political country. At the same time being westernized you can never truly be Japanese nor do post war Japanese coming here necessarily see you as Japanese.

There is a vacuum of identity. You cannot thrive if you feel there is no home for your soul. You have a choice - disappear or stand up and find yourself, build your own identity- no shigata ga nai.

With the JC Redress I began to discover just how much was taken away from me as a person, as a human. The records of the Children’s Aid Society were carefully constructed by the very people who didn’t care. It showed that there was no history of my family or connection to the greater JC community. Before my mother died at age 42, I spent time with the Nakano family in Toronto. Leatrice, the youngest daughter and I were about the same age so we played together.

Only after Redress I did realize what had happen to the JC population and that my stepfather was imprisoned in the prisoner of war camp in Shrieber in northern Ontario.

At the age of 6-7, I was chased from where my mother and I lived to the streetcar stop which stopped at the school where I went to kindergarten or grade 1. One day the boy who was older, caught me just in front of my home and beat me to the ground saying “I hate you. You dirty Jap. You killed my father’s brother! Why don’t you go back to where you belong?”

It wasn’t until I was in my early 20s that doctors discovered my lower sacrum and tail bone had been broken off, and fused on the inside of my spine. My mother realized she could no longer protect me and sent me to her brother’s family in Coaldale, Alberta where I lived with this family for a little over 2 years. This was not a good time for me as the family was struggling with having another mouth to feed and my aunt, much younger than my uncle already had three children.

Finding the Nikkei in me has required a lot of introspection and it cannot be separated from what I imagine I inherit genetically from my parents but here is what I consider Japanese in me: A love of certain foods without really understanding why they comfort me. An ability to flex when needed and resist when required in a way that understands the danger of both. A sense of collective necessity as a human power to transcend challenge. A deep love of nature and a longing to understand the language of nature and how to be in harmony with it.

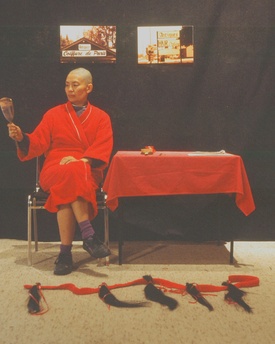

Photo: Haruko Okano.

Wabi Sabi

There has been an innate resistance to emotional expression that I have had to overcome in order to find my own voice and there is still remnants of that in me. I find JCs not especially demonstratively affectionate in public nor emotionally expressive perhaps that is superficial but I feel history may have made us so.

Autonomy is something that comes from the JC history where whole communities were interned together. Having been isolated outside of that has meant that community, collectivity maybe a Japanese trait and so my work outreaching to communities of different descriptions comes from that sensibility. One chopstick alone is easily broken but a bundle of chopsticks is much stronger. I have a sense of loyalty to the JC history, sense of community and to justice regarding them and that has broadened to an empathy imbued with personal experience that informs my work in human rights and social good.

I have taken JC off the pedestal of idealism and understand more of JC as humans like other humans burdened with all the foibles and strengths that other humans express. We are not perfect. Part of my creativity I believe is also Nikkei especially when I look at the overall nature of Japan and how it has observed what is being made the best in the world and then does it one step better. This type of observation, reflection and innovation is in me … that is Nikkei. Nikkei farmers and fishermen thrived here where the Caucasians in the same disciplines were perhaps not as successful. I believe because we have these traits combined with the willingness to work hard that is Nikkei. That is in me.

Have you ever been to Japan? If so, what was that experience like? If not, why not? What connection, if any, do you have with Japanese culture? What is its influence on your art and life? Can you understand how some artists might want to distance themselves from “Japan”?

I have never been to Japan. I don’t speak Japanese. I believe my love of Japanese culture predates contemporary Japan and I can see that the modern Japan doesn’t really appeal to me.

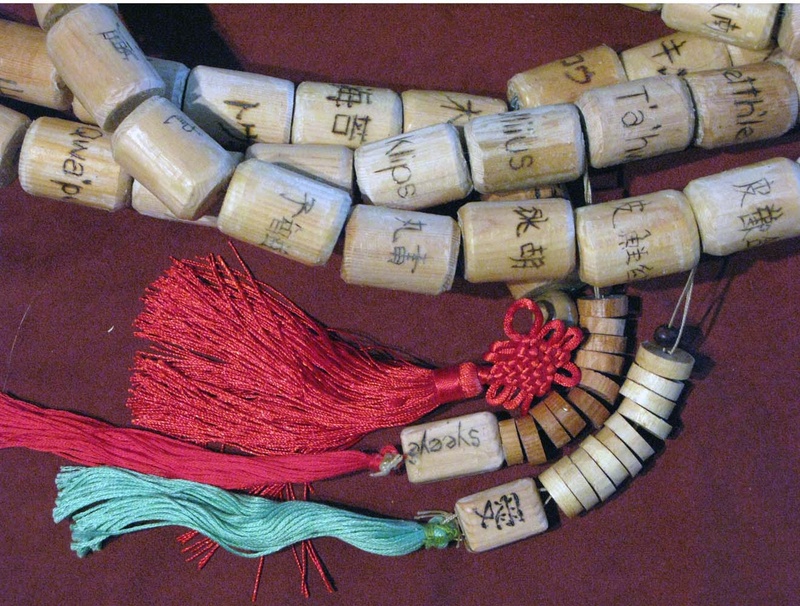

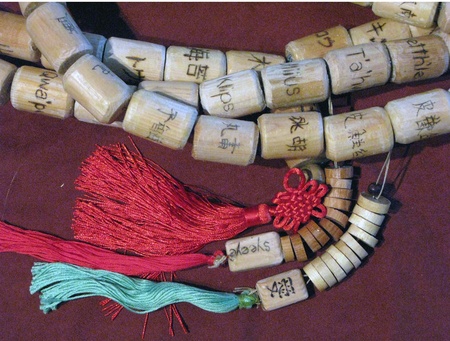

My connection to Japanese culture is more with the aesthetics- Wabi Sabi. I understand this. It is the innovation of the earlier era that has still some traces left in modern Japan. It is when I work with materials like Kakishibu, kiyori, allowing nature to have a distinct presence in my artwork that I believe is my expression of bringing Japanese tradition into contemporary expression.

My mother was raised in Japan as a young child and brought back to Canada at the age of 18 or 19. I know that she saw a freedom here that she had not witnessed in Japanese culture and she wanted to be part of that freedom. There are cultural, social restrictions that Japan has that for westernized Japanese would be a challenge. I know I would be ostracized. I can understand from seeing young Japanese women coming here why Nikkei women might find it frustrating as women in Japan.

Can I touch on the topic of community? How in touch are you with the non Nikkei community? What is your relationship with the Nikkei one in Vancouver e.g., Powell Street?

My first connection to the Nikkei community in Vancouver was Powell Street Festival. Remember I didn’t feel Nikkei...how could I? I came back to Vancouver to find the community and lived on the skids next to the past location of old Japantown hoping to find the community that was inferred by my memory of the Buddhist church. There was no visible community. The festival which happens once a year at that time was like a tourist attraction. Lots of karate, judo, foods, dance and music but I didn’t get a sense of community that was continuous.

I began to understand how deeply the anti-Japanese sentiment that interned and imprisoned the community had in many ways destroyed it. The fact that the Sansei intermarried with predominantly other races following the war years means that visually we are no longer a distinct target but we are also not a distinctly identifiable community. I play with this in my art because we are not the only culture that struggles with identity under the pressure of westernization. High(bridi)Tea collaboration with Fred Wah was both an installation, storytelling and political/cultural look at Hapa.

© 2016 Norm Ibuki