Sumo—in which two hefty, virtually naked men push, shove, and throw each other—probably looks like an exotic sport to most Americans. Young Japanese Americans, like other Americans, are likely to think that sumo is part of traditional Japanese culture, not Japanese American culture. Yet before World War II sumo was an important part of life in Japanese American communities, especially in Los Angeles and the San Joaquin Valley.

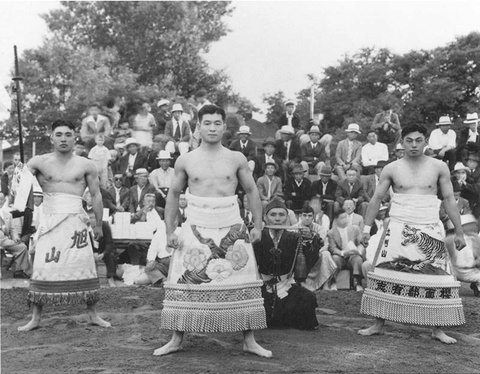

Three Nisei in kesho mawashi, Fresno, June 19, 1938. Asato Yamamoto, Mitsugu Hamanaka, and Mitoko Kawaguchi. Hamanaka became the “Yokozuna” of the Nisei. Gift of Mitsugu Hamanaka. Japanese American National Museum (97.29.4).

Issei and Sumo: From a Village Tradition to a Locus of Issei Identity

Sumo, rooted in rural Japanese villages where the vast majority of Issei originated, was part of Japanese immigrant life from the very beginning. In rural Japan sumo was not a sport; rather, it was a folk Shinto ritual in which gods were thanked for the year’s good harvest. During summer and/or autumn festivals, villagers made a sumo ring around a local Shinto shrine. Showing their mental and physical purity by taking off all their clothes except for their mawashi (loincloths), local men competed while the rest of the villagers gathered around, enjoying sake and feasting in a festive atmosphere.

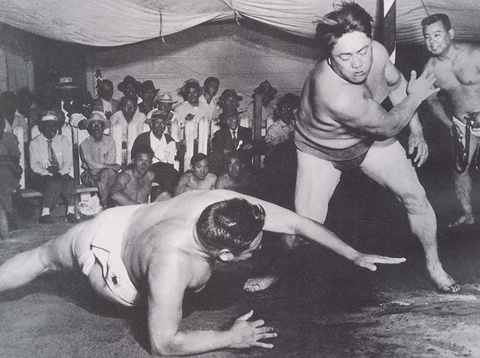

Sumo tournament, Sacramento area, ca. late 1930s. Gift of Fumi Shibata. Japanese American National Museum (97.99.5).

In America, Issei (first generation Japanese immigrants) continued the familiar practice at the end of the harvest. Though there was no Shinto shrine, the immigrant farmers and laborers expressed their gratitude to the harvest gods through sumo. There was no single “pioneer” who brought sumo to the United States. For the Issei, sumo was part of the culture which they lived and practiced every day.

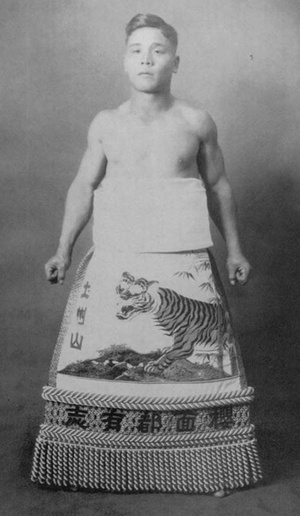

Portrait of Toshuzan wearing kesho mawashi. Toshuzan or Toyomori Hosokawa was one of the strongest Issei wrestlers in the Sacramento area in the 1920s. The kesho mawashi was given by his supporters, primarily from the same prefecture. Gift of Atsuyoshi Hosokawa. Japanese American National Museum (97.3.7).

After the turn of the century sumo acquired a special meaning in Japanese immigrant society, transforming from a ritual/recreation to an organized community affair. In 1907 a group of professional sumo wrestlers was dispatched from Japan to Washington, D.C. to deliver a commemorative sword to President Theodore Roosevelt in appreciation for America’s support for Japan during the Russo-Japanese War. After performing the ancient sumo ritual in front of the White House, some of the Japanese wrestlers decided to remain in California where they taught Issei enthusiasts the art of sumo. The resulting sumo “boom” led to inter-community sumo tournaments from Los Angeles through the San Joaquin and Sacramento Valleys. Sumo became one of the most important social events in Japanese American settlements, rallying community members and strengthening a sense of Nikkei (Japanese American) identity. It was the beginning of the “Americanization” of sumo.

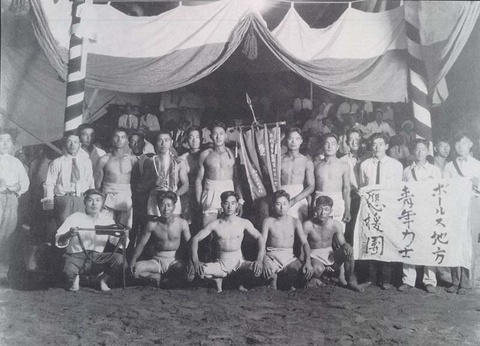

In the Sacramento area, for example, local Japanese American communities got together to hold an annual sumo tournament on Independence Day, after the asparagus harvest. Immigrant leaders and entrepreneurs from various locales donated expenses and prizes and others offered their time and labor. Regardless of the differences in age, occupation, and prefectural origin that divided the Issei, everyone was willing to cooperate for this important annual event. It was a rare occasion on which not only farmers and merchants, but also young migratory laborers, shared enjoyment and community spirit. It is particularly significant that sumo made a place in the community for working-class Issei, who tended to be marginalized in the Japanese immigrant society. Farm laborers, naturally trained by their work, were among the best sumo wrestlers.

Fresno County Youth Sumo Tournament, July 4, 1926. Gift of Toshi “Dyna” Nakagawa. Japanese American National Museum (97.14.2).

There was strong competition among the local communities: Sacramento, Courtland, Walnut Grove, Isleton, Vacaville, Woodland, Elk Grove, and Stockton. At the tournament held at the ring in downtown Sacramento, each community was represented by the local yokozuna (grand champions) and ozeki (second-rank champions) who strove to defend the honor of their families, friends, and neighbors. Volunteers formed a cheerleading squad with drums, gongs, and banners; spectators rooted for their favorite wrestlers, throwing money and presents into the ring when they won. Some of the best sumo wrestlers were even given elaborate kesho mawashi (decorated sumo aprons).

Japanese immigrant sumo on the mainland reached its peak with the visits of Hawaiian wrestlers and Japanese college sumo delegations in the 1920s. These visits helped the formation of distinctive Nikkei identities in California, even while promoting ties between the usually quite separate Hawaiian and mainland communities and reinforcing links between Japanese immigrants and their native land.

In 1924 and 1927, the “American-Hawaii Joint Sumo Tournaments,” in which a group of Hawaiian sumo wrestlers met the best of Southern California, were held in the heart of Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo. According to Chaplin Matsunomori, a popular Hawaiian sumotori (sumo wrestler), the mainland wrestlers, who received the full support of the large crowd, overwhelmed the Hawaiian delegates in both tournaments.

In 1925 and 1927, Japanese college sumo wrestlers visited San Francisco and Los Angeles. In the wake of the 1920 Alien Land Law and the 1924 Immigration Act, these visits were of special significance to the Issei who were buoyed by what they believed to be the encouragement of many people across the Pacific. Defined as “aliens ineligible to citizenship,” Japanese were categorically excluded from land ownership in California and prohibited from further immigration into the country. Understandably, many Issei were so dejected and angry that they gave up on the United States and returned to Japan. Those immigrants who chose to stay in California struggled in a hostile environment, but they were often encouraged by the support they received from their families, friends, and other sympathetic people in Japan. In the context of American racism, the visit of the Japanese college wrestlers seemed a concrete example of support in the Issei’s eyes and gave them a reason to take pride in their heritage and ethnicity. Sumo had changed from a village tradtion to a locus of ethnic identity and community ties in Japanese America.

*This article was originally published in the Japanese American National Museum Quarterly, Fall 1997.

© 1997 Japanese American National Museum