“Give me liberty or give me death!” was the climactic closing statement of a speech given by Patrick Henry, in 1775, as one of the leading founders in America’s fight for independence from England.

Jack Muro, who was born December 3, 1921 and raised in Winters, California said that he and his friends loved America and all grew up very patriotic and believed in all the principles of democracy won in the hard fought battles for independence. They learned their country’s proud history as students and wished for the same democracy for all countries throughout the world.

After graduating Winters High School, Jack moved to Los Angeles to work with his uncle, Kazuo Funai in the produce market. Jack’s parents, Tokuichi and Koito (nee Funai) followed shortly after. Later, when he heard from his caucasian school friends he grew up with that they were going to enlist in the military, he wanted to join as well. They were concerned about what was happening around the World.

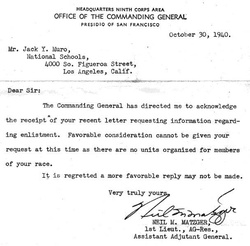

Jack applied to every branch of the military and was turned down by all. He then wrote to the War Department in Washington, DC who passed Jack’s request along to the Office of the Commanding General in the Presidio in San Francisco, and they turned him down yet again with the letter (right) stating:

“Favorable consideration cannot be given your request at this time as there are no units organized for members of your race.”

He was devastated, and quite frankly, “I was angry!”

Then the next year, on December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in the U.S. Territory of Hawaii. The next day, the United States declared war on Japan, which consequently led to the anti-racial and economically motivated expulsion of Japanese living in America’s western coastal states: Washington, Oregon, and California. They were forced from their homes and businesses and held captive in military-style camps for the duration of war. The Muro family, along with up to 120,000 of America’s Japanese from the West Coast states, was swept up in this massive forced migration. The Muro family ended up in Amache, Colorado, one of the ten concentration camps scattered throughout the “badlands” of the USA.

When the US Army eventually allowed Japanese American men in these camps to join the military service, Jack refused. Jack said he would have joined, but he was still angry after being harshly rejected when he tried to join the army in 1940 and now, imprisoned. So, when asked by the US Army Major who came specifically to visit him in Amache to ask why he refused, Jack held up this letter to the Major and said, “No question, I would join if my family and I, along with all the other Japanese being held were free, but NO, because we are not free.”

The Army Major had no response and left. Jack Muro said he thought at that time of that well-known statement by Patrick Henry, especially the words—liberty and death.

So now that he and his family were without their liberty, was it alright for him to face possible death in war? “This didn’t make any sense and was wrong,” said Jack.

By now, Jack was gratifyingly active with his photography and his many camp jobs. Had Jack joined then, we might never have had The Underground Photographer and all his wonderful photographs, his visual records of camp life in Amache.

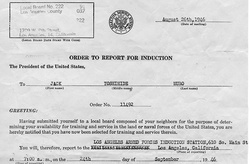

Jack and his family, and up to seven thousand others, served out their “full-term,” three-years-plus in Amache and the Muros returned to Los Angeles after their release. Ironically, shortly after resettling in Los Angeles, Jack received a “Greetings:” military draft letter and was ordered to report to the Armed forces Induction Station. Jack, now finally free, patriotically and dutifully reported.

Again, Jack’s life is interrupted. Jack was just beginning a courtship with Kate Kei Tanji, sister of Taro, one of his best friends in camp. They were all in the same 6H block in Amache. Jack said he hardly knew Kate in camp because she was so busy working in the Amache hospital.

They got to know each other more when Kate and her sister Julie was planning to drive their family car home to Livingston, California following their release from Amache. Jack “did not want two women to go unaccompanied and offered to drive them home.” After that very long drive from Colorado to California, Jack and Kate kept in touch. Because Kate had expressed wanting a dog, Jack who was living in Los Angeles picked one out for her and drove the dog all the way to Livingston, almost 300 miles away!

Now, that they had the liberty to strengthen their relationship, a greater separation loomed. Oh well, they say, “Absence makes the heart grow fonder.”

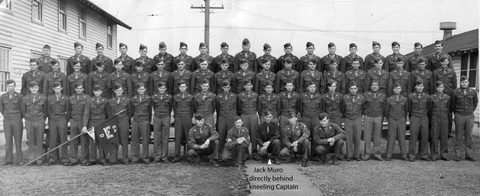

Jack was sent to Fort Lewis, Washington for basic training where it was suggested that he might like to join the Military Intelligence Service detachment of Japanese Americans. Jack said, “No, I don’t want to be a part of a racially segregated unit, I am an American!” So, Jack was trained in the 64th Engineering, Detachment Company, pictured below, after which he was directed to serve in the 54th Engineering Maintenance Company in Occupied Japan. Jack was the only Asian in the 54th company.

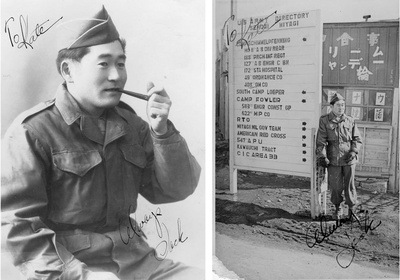

Jack served in Sendai, in the Miyagi prefecture where the devastation of the 2011 tsunami following the off shore magnitude 9.0 earthquake took place. Here are two pictures of Jack taken in 1947, still showing the evident after affects of the 1945 World War II aerial bombings, which strikingly resembles some of the 2011 post-earthquake and tsunami damage photographs.

Of course, “heart-struck” Jack was corresponding with Kate. He sent her these photographs below.

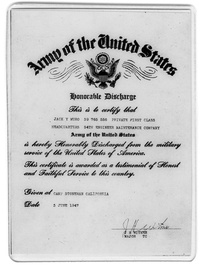

Jack was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army following his tour of duty in Occupied Japan. Jack and Kate were married at Hongwanji Temple in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles.

Following helping his father in his gardening business, Jack worked as an auto-mechanic, went to school, and then worked with the LA City Civil Service. Taking advantage of vocational classes along the way, Jack worked his way up in the city from light equipment mechanic to becoming the regional construction and maintenance supervisor. He retired after 26 years of service to the city. They have a son, Dr. Allen Yoshio, an anesthesiologist with Kaiser Permanente and a daughter, Jeanne Yoshiko, animal keeper at the Los Angeles Zoo. Jack and Kate still live in the house they brought in the 1960s just a short hop east of Downtown Los Angeles and Little Tokyo.

Despite his earlier rejection from serving in the U.S. Armed Forces, Jack eventually did serve and received his Honorable Discharge, which states, “This certificate is awarded as a testimonial of Honest and Faithful Service to this country.” Jack is still patriotic after all this and believes in America. Jack hopes that democracy will work to remain strong and not repeat the mistake of violating the constitutional rights of any groups of people, ever again.

Happy Independence Day from Jack and Kate Muro!

© 2013 Gary T. Ono