In addition to the scenes I mentioned last time , this old film contains footage that is deeply connected to my family. It is about the Dourados colony project, to which my father devoted his life. I cannot help but feel a strange fate in having this old footage in my possession even now.

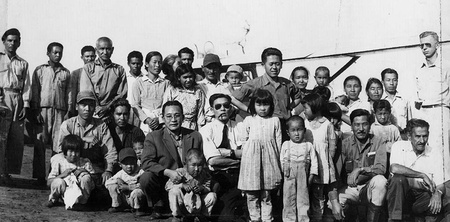

My father, Suemitsu, and mother, Toshiko, holding my younger brother, Munemitsu, and in the front row, me and my sister, Yukiko (1951)

My parents' family moved to Apucarana, Paraná, in 1945. My father worked as a dental technician and as a temporary dentist around farmland. After the war, he was also the head of the Paraná state branch of the magazine "Hikari," published by the winners.

So at that time, there was a sign for the magazine "Kouki" in front of our house. One day, members of the Recognition Movement took a photo of it and handed it over to the political police. As a result, my father was arrested and incarcerated in the prison of the city of Londrina. From there, he was released a few days later thanks to the efforts of his friends.

My father was tired of this lifestyle and was constantly searching for a business that suited him. That was when he heard about an untapped piece of land owned by the Paraná state government. So in 1948, my father started the Dourados Colony.

In the old film left by my father, there is a scene where he reads out the mission statement for the business in front of the grave of Shuhei Uetsuka (1876-1935), who is said to be the "father of Brazilian immigration." Also, the video recorded in 1951 shows the site of the 60,000 alquer(*) Dourados colony project.

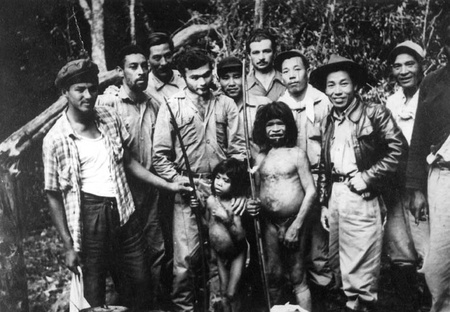

This colonial project was a development project that began in 1948, three years after the end of the Pacific War, with the approval of the Paraná state government. My father was 34 years old at the time. At the time, the Dourados settlement was a dense jungle area inhabited by Chetas Indians, who would come to get corn and other produce grown by the Japanese in the settlement.

Four years after my father began his pioneering career, the Paraná state gubernatorial election took place. This election would have a major impact on my father's future.

The incumbent Governor of Lupion was pushing for his successor, Minister of the Navy Gomes, who was from the same ruling party that President Zutra supported and who had been promoting the development project. Naturally, so was my father. Meanwhile, the opposition candidate for Governor Bento was a member of the faction of Governor Adhemar of São Paulo, who supported the former dictator Vargas, and was not very interested in the development project. After a fierce battle, contrary to expectations, the ruling party candidate was defeated. As a result, although civil engineering work had already progressed in the Dourados colony and some settlers had moved in, the colonization project by my father and the previous Paraná government was halted. In the end, the scale of my father's Dourados colonization project was reduced to less than one-third, and the remainder was handed over to a group supported by the São Paulo state government.

The cancellation of the colonization project became a major political issue. The ruling and opposition parties began to fight in the newspapers, and my father was also criticized by Japanese newspapers. The issue also developed into one of "winners and losers," and the matter became a quagmire.

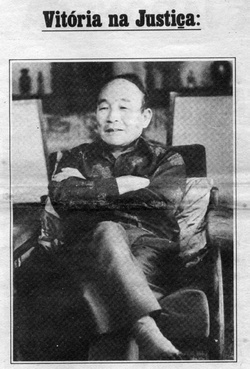

The big dream that my father had been working on changed drastically. My father, who had a fiery temper, was forced to take the state government to court in 1954. A tough and bitter battle began for the Miyamura family.

After an incredibly long time, the verdict was finally reached. It was in 1985, 31 years after the trial had begun. My father, who was already 71 years old, had finally achieved victory. However, his struggle continued for another 10 years until his death at the age of 81. He lived his life with the determination of a man of the Japanese Empire and the conviction to never give up.

Few people at the time could have known how deeply his father's colonization work was intertwined with political issues.

The reason my father took the matter to court was because of more complex political issues. A few years after my father started his business, new political issues were emerging.

Around 1930, when many Japanese immigrants, including my maternal grandparents, moved to the farmlands of Brazil, the Brazilian coffee market was in a dire state due to various problems, including a collapse in international coffee prices due to the global recession, domestic overproduction, and the exhaustion of the soil where coffee was grown. Therefore, from the late 1930s to the 1940s, coffee production gradually shifted to the state of Paraná, which is rich in high-quality "red soil" that is ideal for coffee and cotton production. At the same time, the number of immigrants to Paraná also increased.

At that time, my father was considering whether it was possible to replicate in Paraná the colonial project led by Japanese immigrants that had been successful in São Paulo. While touring the farmland, he happened to make the acquaintance of the Paraná government's land manager for undeveloped land. He found out the name of the state's Secretary of Agriculture, and after taking the business proposal he had written, he requested an interview with the Secretary through an interpreter named Kanayama, a second-generation Japanese student studying at the National Law University in Paraná, who had been introduced to him by an acquaintance from his time living in Santos. And so my father's development project began.

After that, my father met with Governor Lupion and hit it off with the other governors, and the project was steadily put into action. My father's efforts bore fruit in 1948. It was a time of great turmoil in the Japanese community in the state of São Paulo after the war, and I now think it is hard to believe that he was able to realize his dream at that time.

But just as it was reaching its climax, something unexpected happened.

Coffee harvested in the state of São Paulo was transported by rail from the production areas to the port of Santos, from where it was exported overseas. The railroad was built with investment from a syndicate of British capitalists, and the land along the railroad was put up for sale by real estate companies, with about 30 kilometers on either side of the railroad becoming the property of the railroad operating company. In this way, the railroad was extended to the state of Paraná. At the time, the railroad extended to the city of Apucarana, where we lived, but Dourados was 400 kilometers away from there.

Just as my father's business was beginning to bear fruit, some politicians in the state of Paraná had a plan to prioritize the export of high-quality coffee grown in their state by using a route that crossed the central region of the state and connected it to the port of Paranaguá, and to build this line. This plan naturally clashed head-on with the will of Adhemar de Barros of São Paulo. And my father's Dourados colony business was coming under scrutiny from politicians supported by the capitalists of São Paulo. After all, the state of São Paulo had overwhelming power, and there was little chance of winning politically.

A catastrophic loss to the opposition in the gubernatorial elections sent the fledgling enterprise into a tailspin: the Dourados colony was reduced to only what had been paid for, and the rest was transferred to politicians and businessmen from the state of São Paulo.

This old film seems to support the fact that the business dream that my father devoted his life to became a 30-year-long legal issue.

Among the people I have recently met are some who came to Brazil as Cotia Youth Migrants 60 years ago in 1953, when the ban on Japanese immigration was lifted after the outbreak of the Pacific War. Among them was one who set out to farm in Paraná in 1963. The Dourados Colony was the land my father had dreamed of in his youth, but he gave up the development project he had devoted his life to, swallowing his tears as he gave it up. They told me about what it was like when they set out to farm.

Being able to watch this old film with these people is a mysterious coincidence, or perhaps the power of fate, and now, 65 years after my father's dream, it makes me think about the mysterious truth of the universe.

Committee for the 60th anniversary of the resumption of postwar immigration. A person who settled in the Dourados colony (third from the right), and the author (2013) are on the far left.

(*) 1 arcaire = 24,200 square meters

©2013 Hidemitsu Miyamura