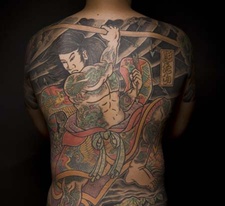

Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World is a groundbreaking photographic exhibition opening at the Japanese American National Museum on March 8, 2014 that will explore the artistry of traditional Japanese tattoos along with its rich history and influence on modern tattoo practices. Horitaka (Takahiro Kitamura), also known as “Taki,” is a 1.5 generation Japanese American tattoo artist from San Jose, California. He is the curator, as well as one of the seven artists featured in the exhibition.

Taki was born in Japan but moved to America with his parents when he was two years old. Although he didn’t grow up in areas that had large Japanese American communities, he grew up surrounded by Japanese culture because of his parents.

“My mother especially made a point to share Japanese culture with my sister and I, she taught us Japanese, cooked Japanese food, and even read us Japanese fables as bed time stories. I think it has to be a difficult balance, to want your children to know their heritage and also balance that with the new country you are living in. I really appreciate my parents... when I was young I had no idea about these sorts of concepts and looking back I probably took a lot of it for granted—I know now that my life has been enriched immensely by what my parents taught me. I am also grateful that my parents were involved with my childhood, not just in terms of Japanese culture—my mother really went the extra mile: packing lunches, sewing Halloween costumes, I am a very lucky person.”

Taki’s initial interest in tattoos did come from a Japanese influence, “though this was juxtaposed by the fact that [his] parents, like most Japanese of their generation, were vehemently opposed to tattoos.”

“The first tattoo exposure for me was Toyama no Kinsan, a chambara show in which the hero showed his sakura fubuki (cherry blossom and wind) half sleeve at the end, and climactic fight scene, of the program. I thought it was the coolest thing ever!!! This was the first spark. Later in my high school years I picked up Ed Hardy’s Tattootime books (the most influential tattoo publications of all time in the US) and was floored. I immediately gravitated towards the Japanese designs and in high school, I had already decided I wanted a body suit—though at the time I really had no idea what that entailed or even really, what that was.”

“As far as becoming a tattooer, that happened later. I got my first tattoos in high school, and then continued to get tattooed while I was attending UC Santa Cruz. The notion of becoming a tattooer in those years was daunting. The tattoo world was much more secretive and underground and I had no idea how to become a tattooer. So I went about my life, graduated college, and worked until an opportunity to apprentice came up. I do remember distinctly when I decided to become a tattooer—and it was scary, I don’t even think at that time you would have considered it a career—more like an unknown path that I just had to set out on. Thankfully, it has worked out for me, but at the beginning it was uncharted territory for me. It was just something I had to do.”

When it comes to Taki’s influences as a tattoo artist, it isn’t just one thing, but a number of things that influences his work as a tattoo artist. “Firstly, my studies in Japan and with other Japanese artists has shaped my work and taught me the basic building blocks of the Japanese tattoo. Included in this, and I think it’s safe to say this applies for everyone doing Japanese tattoos, is a rigorous study of Japanese art—all of it, with a focus on Edo period woodblock prints. Japanese tattooing cannot exist without Japanese culture, its history, folklore, symbolism, and what my parents taught me certainly helps with my understanding of this. Spending time in Japan is also very important, you have to live the culture, visit the temples and shrines. I think everything can influence art, anything that inspires you to create—music, movies, paintings, other people…”

When Taki went to Japan to get his back tattooed by Master Horiyoshi III, an experience which would then culminate in a ten year apprenticeship, Taki was introduced to “the world of Japanese tattooing.” Since then, Japanese tattooing has been something that Taki has devoted his life to studying. This can be seen by the opening of State of Grace Tattoo in San Jose, California—a private studio opened by Taki that was initially intended to focus on Japanese tattooing.

“[State of Grace] has grown over the years to a 3,000 square foot shop with a wide range of styles. Our main area of expertise is still Japanese tattooing [and] we also publish books.”

Taki’s devotion to promoting the Japanese tattoo tradition as an art form can also be seen by the numerous books he has published on tattoo art and culture; his lectures on Japanese Tattoo at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, UC Santa Barbara, and at conferences in Italy and Hawaii; and his dedication to the upcoming exhibition, Perseverance.

State of Grace is located in Japantown in San Jose, California—“The Japantown space fit us perfectly and to us, it made sense, Japanese tattooing in Japantown! There was some grumbling from the community but our landlord stood up for us and believed in us.”

From local projects in Japantown, to the tsunami relief efforts for mainland Japan, State of Grace has been involved in a number of community projects. By combining their talents and efforts, Chad Koeplinger, Horitomo, Roman Enriquez, and Taki were able to donate $18,000 to the Red Cross tsunami relief effort through their fundraising campaign: I Stand With Japan.

State of Grace has also been involved in local community activities through their landlords, the Dobashi family. They face painted for Suzume Gakko (a local Japanese school for kids) a few times, where Shige (Shigenori Iwasaki), a Yokohama-based tattoo artist also featured in Perseverance, was around to help once too. State of Grace has also painted a large mural on the side of a dragon, as well as an electrical box as a part of San Jose’s campaign to “beautify” the city.

Taki has also been involved in Sake San Jose, a fundraiser benefiting Yu-Ai-Kai Senior Service.

Namely, by creating shirt designs for the year of the tiger, rabbit, snake, and dragon—some of which were used for Sake San Jose’s posters. Horiken, a tattoo artist whose work has been shown internationally and whose work will also be featured in Perseverance, also designed a special poster for this fundraiser.

“You have to ‘support your local,’ if we don’t, who will? My parents instilled a ‘community service’ type of thinking in me from the start, from boy scouts, to volunteering. My college major was Community Studies. It just seems right. In particular I like to do things with the senior center—my parents taught me to respect my elders and especially with JA seniors and what they went through with internment…they deserve our respect!”

Perseverance is more than just displaying Japanese tattoos, it strives to establish the Japanese tattoo tradition as an art form, and to explore its rich history and influence on modern tattoo practices.

In a similar way, Taki is not a one-dimensional tattoo artist, but rather, he is an artist on a mission to study and share Japanese tattooing with the world, with all of its rich history, artistry, and legacy. Like Japanese tattoos and its influence on modern tattoo practices, Taki is a 1.5 generation Japanese American with numerous influences, and a fusion of cultures that bleeds into his work—whether it be publishing books, lecturing, serving the community, or tattooing.

* * *

Curated by Takahiro Kitamura, and photographed by Kip Fulbeck, Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World will be on view at the Japanese American National Museum from March 8, 2014 through September 14, 2014.

This exhibition features the work of seven internationally acclaimed tattoo artists, Horitaka, Horitomo, Chris Brand, Miyazo, Shige, Junko Shimada, and Yokohama Horiken, along with tattoo works by selected others. For more information, visit janm.org/perseverance.

All photos are courtesy of Takahiro Horitaka Kitamura.

© 2013 Japanese American National Museum