Read Part 1 >>

3. American Populism: From Exclusion to Redress

Anti-Japanese

A 1907 New York Times article described this as "the Japanese invasion of the white man's world." Soon, the Gentlemen's Agreement was signed, followed by the 1913 California Alien Land Act, the suspension of passport issuance to picture brides in 1920, the 1922 Ozawa Takao ruling that determined foreigners could not be naturalized, and the 1924 Immigration Act that halted Japanese immigration.

I have just picked out three from the tanka. Apart from the law, they also talk about social discrimination, such as not being able to rent a house, and the economic losses they have to endure because they do not have citizenship.

In my heart of anger, the house with the rental note on it is not for us to rent

(Inoue Ijo, "New World," June 24, 1923)I felt like putting my fingerprints on it as a citizen of the land, and that it was a disgrace to my country.

(Usui Chikuma, Shinsekai Asahi, October 7, 1940)The landlords who work hard and earn a living

(Ma Kafumi, "New World", May 23, 1926)

From here on, we will look at his works, focusing on his senryu poems. He laments the reality that he must endure discrimination because he cannot obtain citizenship. From these poems, we can see that the author has realized that the founding principles of America are supposed to be equality, justice, and humanity. However, in reality, he cannot even call his wife, and cannot even marry. He points out that immigration laws are contrary to the spirit of America.

<About immigration law>

I hate the night when there are no people like Lincoln.

(Jakuki, North American Senryu, 1930)Immigration Law: Unable to even call his wife, a lonely grave

(Meishu, North American Senryu, 1930)Immigration law in America preaches humanity

(Kigoubo, North American Senryu, 1930)"Right of naturalization"

The lack of naturalization rights is used to mislead

(Yanagiu, North American Senryu, 1930)Without citizenship, he suffered in silence for days

(Shotei, North American Senryu, 1933)Where is hope in the words "unnaturalizable"?

(Imosaku, North American Senryu, 1932)

Although second-generation Japanese people have citizenship rights, the poem describes the reality that even if they have an education, or can speak English, they still face social discrimination on the basis of race.

Graduation is a milestone in the job market

(Gokain, "Kamae Senryu One Anniversary," June 19, 1938)Only knowing English, the color of my skin is not good enough

(Ryoko, North American Current Affairs, September 28, 1939)Although American justice, humanity, freedom, and equality are instilled in schools, the reality is different. This book points out the contradiction between ideals and reality.

I can't understand the world that is different from what's in the textbooks

(Take Ryo, North American Current Affairs, August 28, 1940)

Even though he was discriminated against as a second-class citizen, he was still drafted, and so his feelings towards America are complicated. Looking at the last verse, we can also sense his pride in having become an adult.

My son was called up to serve in the military and he recited the Stars and Stripes

(Kido, North American Current Affairs, October 28, 1941)Sacrificing my child to a country that won't grant me citizenship

(Jakuki, North American Current Affairs, July 21, 1941)Children raised in the midst of ostracism also became soldiers

(I know, North American Current Affairs, March 18, 1941)

Of course, with citizenship, they should be legally equal, so they place their hopes on the future of the second generation, who are American citizens. Even though they face discrimination, they still have a strong attachment to America. They finally feel that they have put down roots on American soil.

Citizens' right to purchase land for permanent residence

(Fujieda, North American Current Affairs, September 28, 1939)Apart from treatment, the right to vote for second generation

(Kigawa, North American Affairs, January 30, 1941)Negotiating hard for child lease

(Rushan, North American Affairs, February 12, 1941)

The Japan-US war, forced eviction, temporary internment camps

Forced eviction completely destroys the life that the Issei have painstakingly built up. The following senryu poem exudes the sadness and regret of eviction.

The foundation built with blood and sweat

(Yusui Uma Shosha, June 15, 1942)Tears flowed from the fields as we bid farewell.

(Jingai, "The Horse Shed," August 8, 1942)I'll never forget my home, so I'll take the bus back

(Issa, "The Horse Shed," July 11, 1942)My father was detained and my mother was in a military camp.

(Kyusei, Utah Daily News, July 27, 1942)

The next verse shows a first-generation Japanese man wearing geta sandals speaking English, which seems quite mismatched and strange; however, in reality, when it rained the ground was muddy and they had no choice but to wear geta sandals. They were interned because they were Japanese, and yet in the temporary camp they were forced to speak poor English. The verse conveys a critical spirit toward the government that forced them into this lifestyle.

A hut-dweller who wears geta and speaks English

(Kyusui, "Uma Shoya", August 2, 1942)

Concentration camps

Let's look at some haiku poems written in concentration camps. They point out the contradiction in America, which claims to uphold democracy and fight fascism for freedom, taking away freedom itself.

Making America his home and living on the fence

(Dew Point, "Entanglements," August 1, 1943)Putting up fences to block entry into Democracy California

(Kyokusui, "Entanglements," December 15, 1944)The iron fence's spikes face inward toward the camp.

(Kyokusui, "Entanglements," September 15, 1944)

The complex confusion of a Japanese man being asked about his loyalty to America can be sensed from the use of the words "soil," "homeland soil" and "American soil."

Hometown Soil American Soil Register

(The Cicada "Entanglements" March 7, 1943)

I even feel angry that they are asking for loyalty behind barbed wire.

Put up a fence and ask for loyalty

(Sumizu, "Entanglements," February 15, 1943)

What is at the tip of the pen of freedom? What is the meaning of celebrating Independence Day in a concentration camp?

Yes or no, the tip of the pen gives you the freedom to choose

(Hakujaku, "Senryu 48 Wards," August 16, 1944)Independence Day: Preaching the Meaning of Democracy

(Okaue, "Entanglements," September 15, 1944

I feel regret and sadness that in the end, America did not trust the loyalty of its second-generation soldiers unless they died on the battlefield.

Loyalty is recognized in the remains

(Shiratori, Utah Daily News, December 15, 1944)The government says that when the flowers fall, it means loyalty.

(Yoshida Shigeyuki, "Entanglements," September 15, 1944)

He also sees the dropping of the atomic bomb as an act against humanity.

When talking about the tragedy of Nagasaki, American radio boasts that it was a hundred percent successful.

(Itoi no Kiku, "Earth Tsukuni Plateau Poetry")With the new weapon, the justice of the past disappears like bubbles

(Senku Ma, Utah Daily News, September 10, 1945)Where are the values of humanity? Atomic bombs

(Morihira, The Rafu Shimpo, October 8, 1946)

I chose two poems about defeat.

A silent morning prayer for the motherland

(Keiichi, Poston Literature, September 1945)My father floating by the window in my hometown in ruins

(Hakushu, Utah Daily News, October 15, 1945)

Resettlement era

Moving on to the resettlement era, it was not so much a housing shortage, but housing discrimination that plagued the returning Japanese soldiers. As the second stanza says, it makes you feel angry that the Statue of Liberty only welcomes people from Europe, and that American freedom does not extend to Asians.

Housing difficulties to welcome the triumphant return of heroes

(Ohara Jingai, The Rafu Shimpo, May 27, 1949)The Statue of Liberty that will never be built in the American West

(Chouseki Kogan, "Tsubame" January 1950)

And even though JACL has called for anti-discrimination and justice, the right to naturalization has struggled to pass through Congress.

Naturalization law is also a racial discrimination

(Miyuki, North American Senryu, No. 48, March 1950)The voices calling for justice against discrimination continue

(Benicho, North American Senryu, No. 48, March 1950)Preaching about democracy but refusing to grant naturalization rights

(Taga, North American Senryu, November 1950)

However, in 1952, the McCarran-Walter Act finally passed, overcoming the President's veto, and was enacted. Voices of joy could be heard as people finally gained the long-awaited right of naturalization.

You can enjoy the miso soup as it is.

(Kenzo, Senryu Tsubame, August 1952)I got my naturalization right and now I can look up at the Stars and Stripes

(Hakujaku, "Senryu Tsubame," August 1952)Gratitude to the spirits of the war dead: compensation for naturalization rights

(Hakuto, The Rafu Shimpo, December 19, 1952)The courage to naturalize in the world's best country

(Dontsu, North American News, May 2, 1953)

How do you feel about the emotions expressed in senryu poems? I felt that even during the internment camp period, there were no emotional outbursts, and that the criticism was well-controlled. Shimizu Kiseki thought carefully about "our present situation, where we are crossing a log bridge over a ravine that is so deep," and asked for restraint when composing haiku. "This is because I fear that this will have a negative impact on senryu itself, and on Japanese short literature in general" (Shigarami, June 15, 1945). We must not forget that there was screening in the form of judges and mutual selection.

Redress Campaign

Jumping ahead quite a bit in time, I chose four poems from the tanka collection "Shasta no Mine" by Aiko Kadowaki, the mother of Junko Iwami, a member of the California Tanka Association, regarding the redress movement.

We hear good news that the world is becoming a place where the children of the third generation are active.

(Shasta's Peak, p. 171)My parents, who are buried in the United States, will be happy today.

(ibid., p. 171)My father bravely survived the storm of rejection.

(ibid., p. 172)I wanted to show this compensation to my parents who endured the days of Japanese oppression.

(ibid., p. 188)

The poem expresses gratitude to the Sansei for being able to receive an apology and compensation, and also conveys feelings of remembrance for the hardships suffered by the Issei parents. I am glad to be able to conclude this presentation with this tanka.

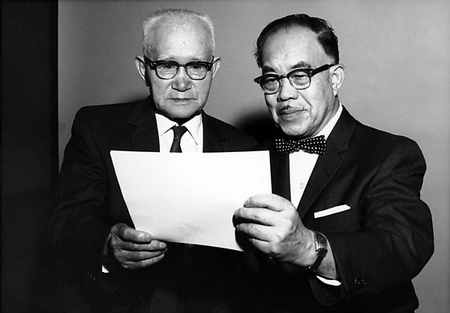

At the New Year's poetry gathering held on January 12, 1966. (Photograph by Toyo Miyatake Studio, Gift of the Alan Miyatake Family, Japanese American National Museum. [96.267.889])

*This is the manuscript of a presentation given in the Japanese session " Issei Poetry, Issei Voices " at the Japanese American National Museum's nationwide conference " Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity, " held from July 4 to 7, 2013.

Listen to this session's presentation (audio only) >>

© 2013 Teruko Kumei