Read Part 2 >>

In 1872, French art critic Philippe Burty (1830-1890) decided to call the new vogue Japonisme—to so christen a new field of study—artistic, historic and ethnographic.1 However, there are other contenders for the first use of the term. Some sources attribute it to French author Jules Claretie, (1840-1913) while others assure it was painter and etcher Félix Bracquemond who launched it, or even the art historian Louis Gonse, (1846-1921). Whoever named it, Japonisme became the most refreshing new way of conceiving, seeing, and producing Art.2 One after another, the ruthless canons on color, shading, texture, perspective, horizon, symmetry, and subject placement were summarily rejected.3

Two significant figures rose to the business opportunities Japonisme had created: Siegfried Bing (1838-1905), a German national who acquired French citizenship; and Tadamasa Hayashi, a young Japanese-trained painter. In 1875, Bing opened a shop in Paris, and through intensive study, observation, and trips to Japan, he became the most formidable source of accurate information the Japonistes, and later the Art Nouveau practitioners, ever dreamed of having around. His businesses soon attracted many French artists looking for inspiration in the Japanese styles. The display of his vast collection of ceramics at the 1878 Paris World Fair brought him enormous success, triggering a piquant comment from Professor Victor de Luynes, French rapporteur for the exhibit, and author of the Report on Ceramics: “Japonism! Attraction of the times, unruly madness that has invaded everything, dominated everything, disorganized all in our art, our fashion, our tastes, and likely our sanity.”4

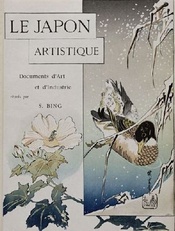

In 1880, Bing created and began publishing his own magazine Le Japon Artistique, famous for its copy, and the reproduction of over three-hundred Japanese original art pieces, in full color. He also enlisted many talented collaborators, including Arthur Lasenby Liberty who later established his own successful enterprise Liberty & Co., in central London.

Then in 1895, Bing opened his gallery La Maison de’l Art Nouveau, where he marketed the productions of artists of that genre. Finally, he emerged as the topmost European dealer for American enterprises, such as Tiffany, Rookwood Pottery, and Grueby Faience.5 Berger says of him, “Without him-and this is no exaggeration-things would have turned out quite differently.”6

In 1878, Tadamasa came to Paris to assist Wakai Kenzaburo, the Japanese Commissioner for l’ Exposition Internationale. After the show closed, Tadamasa remained in Paris to auction the valuable objects left behind. He opened his gallery not far from Bing’s in Montmartre. Though self-educated, he was quite insightful, talented as an art dealer, and an excellent businessman. He recruited his family in Japan to search for valuable objects with which to increase his already precious stock. He was chosen Commissioner General of the Japanese Pavilion for the 1900 Exposition Internationale. Soon after the event closed, he began auctioning his vast stock and returned to Japan.7 In 1902, he authored a fabulous treatise on Japanese Art.8 It seems that, on seeing the European reaction to their country’s art, Japanese artists, merchants and entrepreneurs, all rushed to further agitate the bubbling turbulence.9

There is no space in this piece to detail the full effect of Japonisme on every artist and art style that emerged in Europe during the so called Belle Époque (1890-1914). In his monumental work, Dr. Klaus Berger (1901-2000) shows the avalanche’s trajectory from James McNeill Whistler, Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt, to its most passionate adherent, Vincent van Gogh; and from him to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec; Henri Matisse, Alfons Mucha, Gustave Klimt, and all the other European artists who gave life to Art Nouveau and other thrilling modern styles. Originally written in German, Dr, Berger’s work was translated into English in 1992, and made part of the academic works of the Cambridge University Press.

Of course, people’s eyes could only see what they were trained to see, hence western Orientalism, exoticism, primitivism, naturalism, and other demeaning western- isms, all remained mostly untouched. That is exactly what happened to French novelist Pierre Loti,10 (1850-1923) and several of his contemporaries. Loti was born in Rochefort, Charente Maritime in France, in 1850. At age 17, he joined the French Navy, became an officer, and had to travel frequently to the French colonies. In 1879, Loti wrote his first novel, based on the diary of his experiences in Istanbul in 1876. His lechery in the South Seas, Senegal, Vietnam and other exotic lands was the topic of subsequent books.

In 1883, he pushed the envelope a little too far; straying from his proclivity, he became glowingly indiscrete about the French brutality at the battle of Thuan Ann in Trois journées de guerre en Annam.11 For that, he was nearly booted out of the French Navy.

Viaud/Loti, then 35 years old, arrived in Nagasaki on July 1, 1885, aboard the ironclad Triomphante. On July 7, he ‘married’ O-Kane, a seventeen-year old girl whom he identified as “…a little yellow-skinned woman with cat’s eyes”; and he went to live with her “…in a little paper house.” The tryst lasted until September 18, when he had to leave for China.

Coloring his diary notes with own his feral fantasies, Loti regurgitated the affair into a novel: Madame Chrisantheme. At the tale’s end, he portrays the girl, whom calls O-kiku-san, as quite blasé, more concerned with the quality of the silver dollars he has left her than distressed about the dalliance’s end. Reflective of the public’s quirks about wantonness in exotic places, the tract became an instant success. In the following five years, it went through twenty-five editions, plus a number of translations.12 For the average person, Madame Chrysantheme was the vade mecum of Japonisme… Europe’s vision of l’ame Japonaise (The Japanese Soul.)13

Loti’s myth so infuriated Félix Régamey, (1844-1907)14 that he decided to write another version under the title Le Cahier Rose de Madame Chrysantheme (The Pink Notebook of Madame Chrysantheme). Christopher Reed has produced a delightful translation of that work, together with an excellent review of the entire affair in The Chrysantheme Papers.15

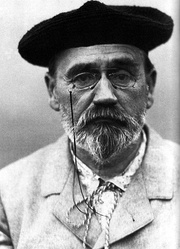

Loti’s Madame Chrysantheme, went through several transformations, theatrical adaptations and embellishments, including several dramas, and even a couple of operas. One, Camille St. Saens’ La Princesse Jaune, failed miserably in 1872, in Paris; the other, Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, also bit the dust when initially performed in Milan in 1904, but later became one of the top favorites among the dilettanti.16Fortunately, more distinguished writers, like Edmond de Goncourt, Siegfried Bing; Émile Guimet, (1836-1918); Émile Zola, (1840-1902); Stéphane Mallarmé, (1842-1898) and Marcel Proust, (1871-1922)17 all treated the Japanese culture more sensitively.18

Notes:

1. Gabriel P. Weisberg, & al., Japonisme – Japanese Influence on French Art 1854-1910, (Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art. 1975), Preface, xi.

See also Gabriel P. Weisberg & Yvonne M.L. Weisberg, Japonisme: an Annotated Bibliography, (New York & London: Garland Publishing, 1990; 163 (294)

2. Giovanni Peternolli, “Reflessi del Sol Levante”, Arte Xilografica Giapponese dei Secoli XVIII-XX, (Bologna: Centro Studi d’Arte Estremo-Orientale, 1999?), 31.

3. For an excellent chronology of Japonisme see Weisberg, op.cit. See also

Pierre Courthion, Impressionsim, transl. John Shepley, (New York: Harry N. Abrams. 1972).

4. Victor De Luynes, Rapport sur la céramique, groupe III, Class 20, (Paris. Imprimerie Nationale, 1882),103. (Translation mine). De Luynes was a professor at the Conservatory of Arts and Crafts, and a juror at the 1873 Vienna Exposition.

5. Bing’s saga is excellently detailed by Weisberg & al. in The Origins of L’Art Nouveau – The Bing Empire, (Amsterdam. Van Gogh Museum, Distributed by Cornell University Press, 2004).

6. Berger, 90-6.

7. Berger, 96.

8. Dessins: estampes: livres illustrés du Japon, (Paris: Hotel Druout, 1902). Digitized by Google.

9. For an example of how Japanese artists responded to the European hunger for Japanese prints and books, see Shotei Takahashi, “Hiroaki-His Life and Works” in DARUMA 57. Winter, 2008.

10. French naval Lieutenant Julian-Marie Viaud (1850-1923).

11. For a sample of how the “most civilized country” could behave in the most barbarous ways, see: http://belleindochine.free.fr/PierreLoti3JourneesDeGuerreEnAnnam.htm (FRENCH). Also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Thuan_An

12. The novel was published 222 times during the life of the author. For the complete text of Madame Chrysanteme, see Project Gutenberg at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3995

13. Loti wrote additional aberrations such as Japonaiseries d’Autumne and La Troisième Jeunesse de Madame Prune, but none were as successful as Mme. Chrysantheme. In May 1891, he was elected a member of the prestigious Académie Française for his profuse literary work.

14. Félix Régamey was a very talented painter, engraver, writer, and a good dabbler at sociology. With the support of his friend, industrialist Émile Étienne Guimet, another ardent japoniste, Regamey became a devoted student of Japanese culture. He also authored, illustrated and printed the novel Ōkoma, the first translation of a major work of Japanese literature (Paris: E.Plan. 1883); and published Japan in Art and Industry. (Translated in 1893 by the Knickerbocker Press, and currently digitized by Google).

15. Christopher Reed, The Chrysantheme Papers, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. 2010).

16. Jan Van Rij, Madame Butterfly, (Berkeley; Stone Bridge Press, 2001).

17. Proust’s voluminous work Á la recherche du temps perdu has often been compared with the monumental, but incomparable Tale of Genji. See, for example, Norma Field, The Splendor of Longing in the Tale of Genji, (Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1987).

18. Jan Walsh Hakenson, Japan, France, and East-West Aesthetics. French Literature 1867-2000, (Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses, 2004).

© 2012 Edward Moreno