It was not possible for thousands of laborers destined for Peruvian haciendas to emigrate from Japan without a contract. Internationally this was "mandatory" since the 19th century, when England dominated the seas and prevented any continuation or restart of slavery in the world. For its part, the English Empire no longer needed the slave regime in its colonies and this is how in London itself there was more than one belligerent Anti-Slavery Society that pressured and demanded the worldwide suppression of the slave trade.

The legal and internationally possible way, consequently, was the immigration of workers from Japan but with the acquiescence - signature - of the emigrants and the permission of the Imperial Japanese State. It must be taken into account that the Japanese emigrants were "property" of the employer or contractor until they completed the work period in the company with which the contract was signed. For example, the San Nicolás Agricultural Society signed several contracts with Morioka. This House, to ensure compliance and be able to make claims, forced emigrants to sign contracts with it equal in content to the one they had with society. On the other hand, the demands were also in the opposite direction: the workers could make their claims to Morioka and the latter to the Company, whenever there was non-compliance. But, if we analyze the content of the contracts and the real possibilities of demand, we can conclude that the greatest precautions were taken so that there was compliance on the part of the laborers. A pending threat on these within the contract was not to give them a return ticket. Furthermore, if there was non-compliance, everyone (the Society, Morioka and even the embassy) agreed that the political and judicial authorities should be resorted to. In September 1908 the House specified to the Society:

"...it is fully understood that any worker who does not comply with the commitment made, you (the Company) have the right to enforce it by going to the political or judicial authorities, when the good reasons are not enough to avert evil. .." 1

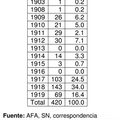

During the years 1897 and 1920, nearly 10 contracts were signed between the Society and the House. The number of Japanese that the House agreed to bring was varied: the first of them was for 150, another for 50, some more for 500. That is to say, it was not a fixed amount for all cases, it depended on the possibilities of obtaining other laborers hooked on the Peruvian mountains or the amount of land available for production.

The terms of these contracts did not differ, but there were aspects that changed as reality evolved and the same experience led to them being more realistic or more demanding. Of all the terms, those of greatest interest were the number of emigrants to be transferred, the time they were going to serve on the hacienda, the remuneration for the workers and the profits of the Morioka. Of all of them, the most contentious points were the first two, particularly remuneration, since there were many pressures that came together: from the Japanese State, from other farms, from the workers themselves.

Despite the differences in these contracts, let's look at the content of the one signed in 1913:

- It was specified that immigrants had to be healthy, between 20 and 45 years of age.

- Regarding the characteristics of the work and payment: the administrator of the estate decided whether the work was carried out on a daily basis or by task. If it was a daily wage, the daily duration should not be more than 10 hours if it was in the fields and 12 hours if it was in the sugar processing factories. But, overtime was paid. And if the work was by task (piecework), the immigrant had to pay "the same amount as those normally done by natives of the country." The daily payment in both cases was 120 thousandths of a Peruvian pound (Lp); that is, , 1.20 soles. And if a proven illness occurred, the laborer received a third of the wages (S/. 0.40).

- In the event of the death of a worker, the Society had to give Morioka House the sum of twenty pounds sterling which was to be given to the relatives or relatives of the deceased, if they claimed.

- The immigrant had to work every day of the year with the exception of Sundays, January 1, July 28, October 31, December 25 and Good Friday. But if the farm required his services and he accepted, he could work on those days.

- The Company was obliged to accept the presence of a foreman if the work was quoted by weight (quantity of cane cut according to its weight); and, likewise, he had to place and pay a Japanese foreman for every 50 emigrants.

- In addition, the Society had to pay the Morioka House 2 and 1/2 Peruvian pounds for each immigrant when the ship left Japan. It should be noted that this was the money that the House advanced as a down payment or contract for each Japanese laborer. The previous condition obliged the Morioka to retain the number of immigrants it had committed to on the hacienda for one year. This advance was returned in case of shipwreck or escape of the Japanese laborers. And if the immigrants stayed two years, the payment to the Morioka rose to 5 Lp., money also given to the laborers.

- The Society had to provide the Japanese laborers and foremen free of charge "medical assistance and a healthy room with its respective kitchen, and a wooden platform six feet long (1.80 m.) by three feet wide (0.90 m.) …”

- If they accepted, the Society was obliged to give work to the immigrants on the hacienda once the contract was concluded. If this happened, the Morioka received 5 Lp. by two years.

Below we present some points of the clauses that were also signed, before or after 1913, and that are interesting to know:

- An amount of money (S/. 0.40) was deducted from the daily wage, which was returned at the end of the contract period. At one time, the House kept that money and later, due to the workers' demands, it was no longer deducted from them.

- To the Japanese, the farm did not give them food; This occurred only in the case of cane cutters who were granted the benefit even though this meant an increase of 13 cents in the cost of production of a ton of cane.

- The Morioka received as commission - possibly this was from the beginning - 10 cents for each task that the Japanese laborers worked on. The hacienda fulfilled this obligation by sending a bill of payment that was collected in Lima by the Morioka.

- It was specified in one of the contracts that if there were bad laborers, the Society could return them to the House on the steamer that passed through the Port of Supe every Thursday.

- Almost at the end of this entire immigration process, an agreement was reached that instead of 1 year of obligation, workers had to complete only 250 tasks. This resulted from the calculation that considered that the actual days of work in a year were 300, from which 50 days were subtracted for illness or non-compliance. This was one more incentive to retain the pawns.

- The Society saw it convenient to insist that before a different contract regarding the obligation of immigrants to work in the cutting and loading of cane, there should only be a clause in the contracts that specified that the Japanese who cut cane would receive 0.45 cents per cut ton of “earned” cane (burned) and 0.50 cents if the cane was white (with leaves and all).

- The Society considered that marriages were more stable and for this reason it began to request them since 1916, following the experience of the Tumán (Lambayeque) and Paramonga (Lima, Fortaleza Valley) haciendas. It was also convenient for them to come accompanied by their minor children, as long as there were no more than two.

- In the contract of that same year it was accepted that all contracted workers could be assigned to cane cutting work.

- In the second contract of 1916, immigrants were required, in additional clauses, not to participate in cases of strikes " and other workers' movements and agitations that could occur in the San Nicolás hacienda and in the neighboring valleys ." If this happened and the Society was harmed, the damages would be paid by Morioka. Curiously, this clause was proposed and was demanded by the House.

- The Society committed itself that same year not to use the service of free Japanese "bracero laborers" nor of other companies or recruiters, it could only do so with Morioka.

- Two advantages convenient to immigrants are considered in an additional clause in 1918. The Society was obliged, according to it, to install a warm water bath for immigrants as well as provide them with half a bushel of arable land. In 1919 it was specified that it was half a bushel per 100 immigrants " without charging rent, so that they could plant their vegetables ."

Appointment:

1. AFA, SN 16 Miscellaneous to Management, letter from Morioka to Company Management, September 18, 1908.

* This article is published under the Agreement between the San Marcos Foundation for the development of Science and Culture of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos and the Japanese American National Museum, Discover Nikkei Project. Lima- Perú, 2009.

© 2009 Humberto Rodríguez Pastor