From before the war to after the war, there were women's educational institutions called "bride schools" in the Japanese community in Brazil. These were schools that taught skills such as sewing and cooking to the daughters of immigrants and trained them to be good wives and wise mothers, typical of Japanese women. Later, some of them developed into comprehensive educational institutions, with high school departments and Portuguese departments that were similar to the curriculum of Japanese girls' schools.

Among them, the three schools known as the "three major bride schools" - Nippaku Jitsugakko Girls' School, São Paulo Women's College, and Santa Cecilia Cooking School - held prominent status within the Japanese community. Many of the women who graduated from these schools married leading men in the community, and many of them also took on leadership roles in Japanese women's organizations. Graduates also opened schools in inland cities in São Paulo and even in Paraná, forming a wide network. In this article, I would like to write about Nippaku Jitsugakko Girls' School and São Paulo Women's College, whose successor institutions still exist today as educational corporations, and about which I have a relatively large collection of materials.

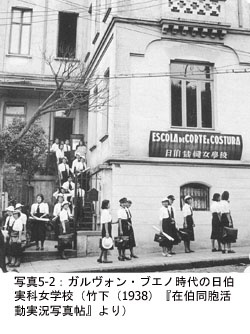

The Nippaku Practical Girls' School was established on March 3, 1932, when Masue Gohara established a Japanese section at a sewing school run by Anna Waldman (Gohara, 1983, p.19). Then, on May 5 of the same year, it became independent as the Nippaku Practical Girls' School and established its school building on Tamandare Street. Soon after, the school moved to Galvão Bueno Street and changed its name to Nippaku Practical Girls' School, and in addition to the elementary, middle, teacher training, music, flower arrangement, cooking, and physical education departments, it also established a Japanese language department (Photo 5-1). It also had a dormitory, and a photo from that time shows that the students were already wearing matching uniforms (Photo 5-2). Later, the school moved to Castro Alves Street in the neighboring Aclimação district, expanded its campus, and also established a Portuguese department. Kawahara Kiyoshi, a former student at Seishu Gijuku (the first medical school student of Japanese descent in Brazil), also taught at the school as a Portuguese language teacher around this time.

Among the educational institutions for women based on sewing schools, the one with a relatively large number of prewar documents is the São Paulo Sewing School (now the Pioneiro School). The school was formerly the "Sewing School" opened in 1933 by Akama Juji and his wife Michie.

According to the 50th Anniversary History of Akama Gakuin Foundation (1985), in April 1933, Akama and his wife opened a sewing school on Travessa São Paulo Street in São Paulo, and on August 1 of the same year, they moved to 18 Conselheiro Furtado Street and renamed the school São Paulo Girls' Sewing School. The following year, in 1934, they moved to 116 Conselheiro Furtado Street. In 1935, they moved to 216 São Joaquim Street and successively established a Japanese language elementary school department, a certification preparatory department, and a practical girls' high school department. The establishment of the practical high school for girls in particular has been noted as a milestone in the history of education for Japanese-Brazilians, as it "responded to the demands of the times (omitted) and aimed to train not only sewing instructors but also future leaders who would play a part in the education world of society, setting a precedent for girls' secondary education in the Japanese community in Brazil" (Sato, 1985, p.72). In April of that year, the school magazine Gakuyu (renamed Gakuyu Kaiga Yamato from issue 3) was launched. In 1937, the Portuguese department was established and the school was officially recognized as a private school under the Brazilian Private School Act, changing its Portuguese name to Escola Particular Acama São Paulo and its Japanese name to São Paulo Jogakuin. It had an attached dormitory, Yamato Girls' Dormitory, and had 70 students in 1938 (Photo 5-3).

These schoolgirls in uniforms walking around the European-style streets of central São Paulo must have attracted a lot of attention. So how did these women's educational institutions survive the difficult times for foreign language education under the Vargas administration from the late 1930s through the war? Gohara, who was the principal of the Japan-Brazil Practical Girls' School, recalled the wartime situation as follows:

- During the terrible Greater East Asia War, when it was forbidden to speak Japanese, we were able to continue Japanese language education, thanks in no small part to the understanding of parents and the arrangements of school inspectors. The inspectors themselves registered the school with the names Nutscreo de Encino, Profición, Libre Escola, and Internacional, because the school faced harsh criticism in Nippo-Brazil. I know that you continue to teach Japanese at your school, but because your school has the noble purpose of teaching Japanese, nurturing Japanese Brazilians, and introducing Japanese culture to Brazil, I have never opened the classroom door, out of respect. However, when I saw you leave your back, leaving behind words overflowing with kindness, asking us not to make it public, I found myself praying several times, like a goddess, with my hands together in prayer (Gohara, 1983, p.19).

It is hard to believe that Brazilian school inspectors in São Paulo at the time knew that Japanese language education was being taught and turned a blind eye to it. In fact, in the case of São Paulo Girls' School, an inspector discovered and confiscated a student's sewing notebook written in Japanese while inspecting the sewing class in August 1944, and ordered the school to be closed (Sato, 1985, p.74). However, as there were cases of Japanese language education continuing even during the war at local Japanese schools, the crackdown by the authorities under the new national system was not uniform, and this may be seen as an example of the fact that some inspectors were quite flexible and tolerant.

In 1941, São Paulo Women's School moved to 849 Tamandare Street. However, in December of the following year, 1942, an eviction order was issued and the school was forced to move to 235 Vergueiro Street, leaving the Liberdade district. The aforementioned "closure order" occurred during the time the Vergueiro school was in operation, and as an emergency measure, the school changed its name to "Escola Vergueiro" and applied for approval to establish a new school, which was approved two months later in October 1944 (Sato, 1985, p.74).

Regarding the content and level of education at these sewing schools, the 70-Year History of Japanese Immigration to Brazil acknowledges their value, stating that "other educational facilities for women (bridal schools, so to speak) such as the Japan-Brazil Sewing School, which opened in 1933, and the Sao Paulo Women's School, could also be said to have been educational facilities that matched the social conditions of the time" (Committee on the Compilation of the 70-Year History of Japanese Immigration to Brazil, 1980, p.310). Even if the Japanese community at the time recognized that educational institutions for women were "bridal schools," whether such an evaluation was appropriate in terms of the content and level of education is another matter.

As advertised in magazines at the time, the Practical High School of the São Paulo Women's College was "established for the purpose of acquiring academic ability equivalent to that of Japanese girls' schools," and "teaching subjects and skills equivalent to those of practical high schools in the mother country" (Kishimoto, 1940). Ms. GW, a graduate of this high school, said that her study of Japanese classical literature at the college was the catalyst for her to devote half her life to the study of the "Man'yoshu" and "Kokin Wakashu." Ms. GW later became a professor of classical literature at the Department of Japanese Language and Literature at the University of São Paulo. From the above, it can be inferred that the content and level of education offered at the school was already far beyond the image of a "bride's school."

In addition to the Nippaku Jitsugyo Girls' School and the São Paulo Women's School, the Fuji Sewing Girls' School (founded in 1941) was also confirmed to have been located on Tomás de Lima Street in the Liberdade district of São Paulo, and interviews with people involved have confirmed that there were other Japanese sewing schools in the same area. The Santa Cecilia Kappo School, one of the "three major bride schools," was also located on the same Tomás de Lima Street. Furthermore, a look at Japanese-language newspapers from that time reveals that there were several sewing schools in regional cities such as Bastos, Lins, and Presidente Prudente. The fact that such education for girls was already flourishing before the war is a notable feature of the Japanese Brazilian community.

References <br />Kishimoto Subaru (ed.) (1940), Wilderness, No. 9; Gyosei Gakuen; Gohara Masue (ed.) (1983), Sisters - 50th Anniversary Commemoration, No. 6; Japan-Brazil Practical Girls' School; Sato Koichi (ed.) (1985), 50 Years of the Akama Gakuin Foundation, Akama Gakuin Foundation; Takeshita Masujiro (ed.) (1938), Photo Album of the Activities of Compatriots in Brazil, Takeshita Photo Studio; Committee for Compilation of the 70 Year History of Japanese Immigration to Brazil (1980); 70 Years of the History of Japanese Immigration to Brazil, Japanese Cultural Association of Brazil

* Unauthorized reproduction or copying of this article is prohibited. Please let us know if you wish to quote. editor@discovernikkei.org

© 2009 Sachio Negawa