Preserving California’s Japantowns (PCJ) is the first statewide effort to identify, research, and document historic resources located in Japantowns throughout California. Sponsored by the California Japanese American Community Leadership Council (CJACLC), PCJ grew out of the energy from community forces rallied around the California Senate Bill 307 (SB307) campaign that focused on protecting the cultural heritage of the well-known Japantowns in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Jose. One of the ways the CJACLC convinced the state legislature to pass SB307 was their reasoning that, of dozens of Japantowns, or Nihonmachi, scattered throughout California before WWII, only three remained with any significant portions vitally intact, and planning for their preservation was critically important. The work that has been conducted in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Jose under SB307 reflects a growing understanding that historic resources in Japanese American communities are crucial not only to California, but to the United States as a whole.

Yet, it is also imperative that advocacy continues as economic pressures and demographic shifts threaten the historic structures, businesses, and organizations that make up these places. SB 307 helped raise awareness both within and outside the Japanese American community that such tangible legacies of the past can only be transmitted to future generations if we identify, protect, and care for them.

California held the largest population of Nikkei in the United States just before WWII, and Japanese Americans resided in nearly every region of the state in 1940. Still, their historical presence is often invisible, resulting from the WWII incarceration that impinged on the physical and social fabric of communities, and had an abrupt impact on individual lives. Few Nihonmachi were able to regain their pre-war vitality. Preserving California’s Japantowns was designed to answer the question raised by the SB307 efforts: “Where were California’s Japantowns and what remains of them?” The project is sponsored by the CJACLC and funded by the California State Library’s Civil Liberties Public Education Program (CCLPEP), which supports projects that document and educate the public about the experiences of Japanese Americans during WWII.

Defining Japantown

Identifying what makes a Japantown and selecting which communities the PCJ project would study were our first important steps. From baseline research we conducted on over seventy communities, we selected a list of several dozen Japantowns in consultation with a committee of expert advisors. The list was based on: size of the community, geographic distribution across California, presence of a critical mass of community institutions, range of commercial activities in both rural and urban settings, and the known presence of historic resources that could catalyze energies toward preservation and interpretation.

Tying the stories and personal memories, the lived experience of California Nikkei, to buildings and landscapes across the state is the ultimate aim of Preserving California’s Japantowns. Our first step toward reclaiming this history has been reconnaissance-level surveys we’ve conducted in forty-five communities. An invaluable primary source for these surveys was detailed listings included in community directories published by Nikkei newspapers just prior to the war.

What remains of historic Japantowns?

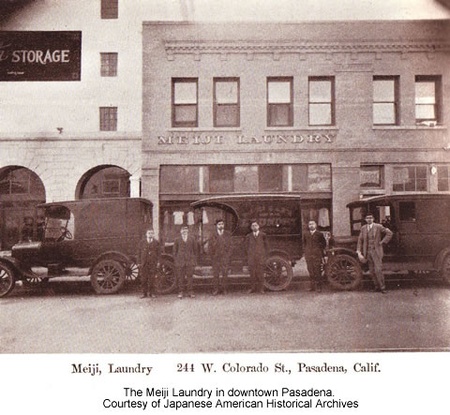

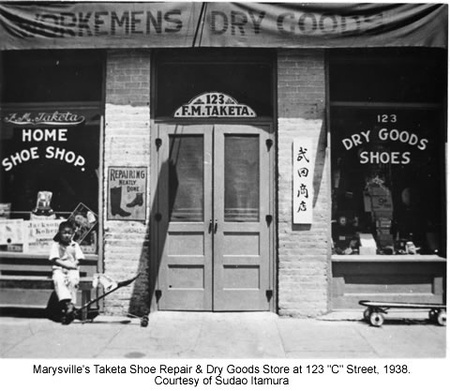

While we expected to find some traces of the vibrant Japantowns that suffered such violent disruption during and after WWII, the results of the historic resource surveys are far more extensive than we had even hoped. We found things that surprised us – such as the dispersed pattern of many Japanese American communities just before the war. While some, like Marysville, fit traditional ideas of a concentrated ethnic enclave, other places like Oakland and Pasadena had Nikkei businesses, organizations, and industries scattered throughout much of the city.

Some places confirmed our fears that this history had been erased from public view. Postwar factors, including access to suburban housing for Nikkei and urban renewal in places such as Sacramento and Stockton, finished off many of the Japantowns that struggled to revive after the war. Santa Barbara is an especially ironic case of this kind of erasure where the historic Japantown was demolished to make way for a state park recreating the 18th century Spanish Presidio. And all that is left of Vacaville’s Nihonmachi, one of the first large Nikkei communities in California, is this section of the historic cemetery and a marker at the former site of the Buddhist Church.

We also discovered that some historic resources faced imminent threats. Lack of awareness and development pressures on these often modest buildings leave them in jeopardy of being demolished. Berkeley’s San Pablo Florist building, which held a Nikkei-owned florist shop from the 1930s thru the 1990s, was destroyed just last December (2007).

But the good news is that PCJ’s statewide survey identified hundreds of extant historic structures that are associated with Japanese American businesses as well as cultural and social organizations across California. However, we found that there is little knowledge of the connection between these sites and their Nikkei heritage.

Everyday Architecture

The vast majority of the historic structures identified by our surveys could best be described as modest vernacular architecture. They generally do not announce their past or their historic significance through their physical form. This is working-class, immigrant history that, for the most part, has been below the radar of landmarks programs and heritage organizations.

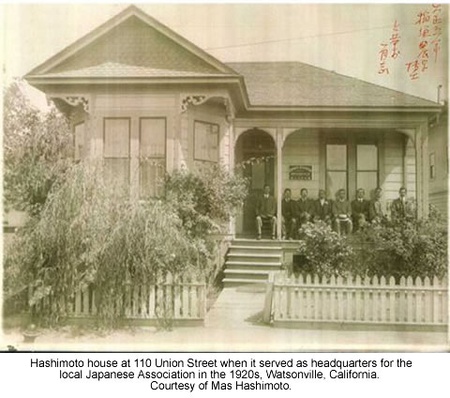

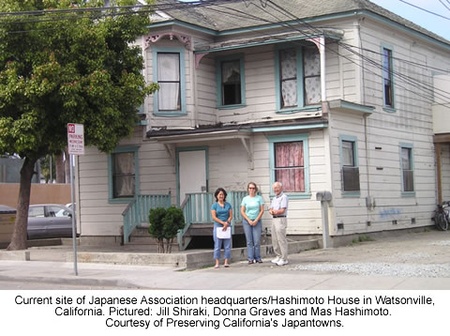

The former home of Mas Hashimoto in Watsonville is a classic example of our findings. His childhood home on Union Street had previously served in the 1920s as headquarters for the local Japanese Association located next door to the Japanese Buddhist Church. When the Japanese Association moved into new quarters, Hashimoto bought the building, moved it down the street, and raised it up a floor, thereby allowing his family to live on the bottom level while renting the top floor out as offices for Dr. Ito. The Hashimotos ran a small udon shop and sake brewery out of the building in the 1920s and 1930s, until Mas’s father died and his mother and siblings began working in local vegetable fields to keep the family going.

Woven History of Ethnic Communities

One of the most interesting aspects of these surveys is the window they open on historic and current relationships between Nihonmachi and other communities. This is a complex topic that deserves extensive study, but the long-time relationship between Japanese and Chinese immigrant enclaves was apparent in many places we surveyed. Another recurring discovery was the vital connection to California’s current Latino population—historic Japantowns are often places where immigrants from Mexico and Central America find a toehold in the United States. We identified numerous structures that once held a Japanese store or community institution now house Latino groups and businesses.

Given the working-class immigrant nature of pre-WWII Japantowns and California’s large population of recent immigrants from Mexico and Central America, this is not necessarily surprising. But we thought it worth noting and contemplating as a potential base for developing interpretive strategies and programs that could connect the experiences of both groups who have shaped and occupied these neighborhoods and structures.

Castroville’s historic Japanese school, now being preserved as the proud centerpiece for a new park in a predominantly Latino neighborhood, is a wonderful example of how these historic connections can be fruitfully explored and built upon. Erected by the local Nikkei community in 1935, the school bustled with activity before WWII and served as a hostel for returning Nikkei in 1946. The building was acquired by the Castroville School District and its connection to local Japanese heritage was lost to public memory until about ten years ago when the local JACL chapter and the County began an effort to transform the historic structure into a youth center. They chose as their motto: Kodomo no tame ni — Para el bien de los ninos — For the Sake of the Children, a goal that has driven generations of immigrant parents to build a new life for themselves and their families.

Engaging Community

As we’ve conducted this ambitious survey, we’ve worked to develop awareness and advocacy for historic resources in places where Japanese American historic sites still exist but have not previously been identified or valued. Press, community groups, and individuals have shown passionate interest in this work.

We are in the process of working with Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association and a wonderful volunteer, Anny Su, to nominate the art studio of Chiura Obata and his wife, Ikebana artist Haruko, for local landmark status. The awareness we’ve raised in Berkeley has led city council to recognize our project and the legacy of Berkeley’s Nikkei community in a proclamation ceremony held in January 2008. City planning staff has gone on record that they will refer to our historic resource survey when they review all demolition permits.

We were able to enlist an enthusiastic cadre of volunteers for our surveys in the Los Angeles and Sacramento areas. Groups representing Japanese American and preservation constituencies helped us reach people in both regions. We organized training sessions and the energized volunteers documented what remains in a variety of historic Japantowns. In addition to enabling this project to reach its ambitious goals, involving volunteers has proved to be an important way to build knowledge of, and stewardship for, historic resources of Japanese American heritage in local communities. These community connections have begun to inspire spin-off efforts such as walking tours, oral history projects, and community exhibits.

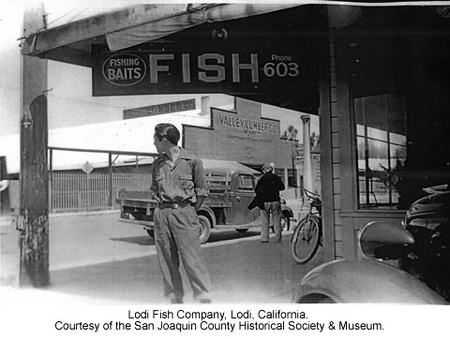

The significance of what we found in the San Joaquin Valley town of Lodi and the outstanding volunteers who have been working there led us to organize a regional preservation workshop with staff from the Office of Historic Preservation and San Joaquin County Historical Society & Museum. Our hope was to lay groundwork for recognition and protection of Lodi’s remarkably intact historic Japantown as the City contemplates redevelopment of the area.

On-Line Resource

Although it was not in our original project goals, we found an opportunity to create a website at www.californiajapantowns.org, that has proved to be an enormously useful tool for sharing our project. Along with interactive maps of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Jose, the site includes an overview of PCJ, selected profiles of communities we have surveyed, a resource page with an extensive bibliography, and links to preservation and Nikkei organizations.

Additional funding from CCLPEP allowed us to expand the website with more community profiles, a preservation toolkit, and a “Nisei Story.” We’ve conducted place-based interviews with Nisei around California and mounted a web prototype for sharing 92 year-old Leo Saito’s recollections of Oakland’s Japantown. We seek funding to complete the website by adding more Nisei stories and all of our survey data so that it can be a long-term source of expanded information for the California Nikkei community, historians, planning and preservation professionals, and local heritage organizations. Sharing the information we have gathered will enable local governments and heritage organizations to more fully understand their community history and to consider options in planning for stewardship and interpretation of their community’s past.

Interpreting Nikkei History

This is an important moment—development pressures around the state threaten many resources that are mostly unknown to local advocates and decision makers. Yet our surveys show we can reclaim space for a richer understanding of the variety of Nikkei experience and the importance of Japanese American history to our state and local communities. And local communities have demonstrated eagerness for this information and the knowledge to put it to use.

What has been striking about this project is how multi-faceted are the potential approaches to using and analyzing the materials we have gathered. The survey findings provide a window into the distinct aspects of Japanese American heritage—especially the uniquely devastating rupture caused by World War II—but they also identified many sites with rich associations shared by other communities, whether it’s through succession of use of a particular structure or commonalities of experience among American immigrants. We hope that you will be intrigued by our work and build upon it in your own areas.

* Donna Graves and Jill Shiraki were panelists in a presentation titled “Preserving a Historic Place: Nihonmachi in California and the Interior West” at the Enduring Communities National Conference on July 3-6, 2008, in Denver, CO. Enduring Communities is a project of the Japanese American National Museum.

© 2008 Donna Graves and Jill Shiraki