For one hundred years, the Japanese presence was present in all areas of Peru, as its members ventured into various public areas. From a pioneering strike in 1899 to a Nikkei president who governed the country's destiny for ten years, passing through athletes, politicians and legislators. While it is true that the Nikkei community has always been in the news, it is also true that it has maintained an ambiguous relationship of integration and distance with its Peruvian compatriots. This duality or double survival strategy (of ethnic secrecy and social charisma) is very interesting, as it relates the ability of those of Japanese descent who have successfully managed their image of strong attachment to Peru without abandoning their Japanese roots. The slogan seems to have been: so that one's own space (the Nikkei community) is not destroyed, public spaces (the political and social life of Peru) must be taken over.

Low profile in the early years

As in almost all the countries where they settled as immigrants, in Peru the Japanese also stayed away from public power. Absolutely all of them harbored the idea of transience and, although they greatly respected the places to which they migrated, caution and a low profile governed their lives as they had to and wanted to return to their original territories. Except for some events reported in the press in 1899, such as the strike of a group of Japanese who worked at the San Nicolás hacienda, its members tried to live immersed within the Japanese community that they were building and where they provided mutual aid and relief. their nostalgia reproducing rituals and customs from the different regions of Japan.

They knew perfectly well that power in Peru was alien to them and that they could only govern their lives as humble immigrants from overseas. So they set about building a colony that would project the same image that Japan radiated to the world. But economic success came very soon and the boast took over, above all, its ruling class. Furthermore, Japan was going through a strong imperialist and expansionist period that made its children proud of their world power. Then, vanity grew like a soap bubble. The immigrants had achieved fortune in Peru and, although fame intoxicated them, now what they really wanted was social recognition.

A Nikkei monument in the public square

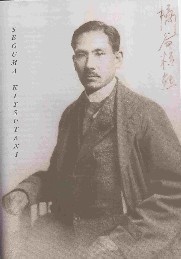

The most powerful man in the Japanese colony in Peru was called Seiguma Kitsutani (Yamaguchi 1873 – Lima 1928). There is extensive documentation that tells us about his interesting life 1 . Unlike the majority, he belonged to the wealthy class, he had studied at the best Japanese universities, he knew the world and came to settle in Peru to dedicate himself to the textile and mining industry. He quickly became friends with the most powerful men (he was a close friend of President Augusto B. Leguía), entered oligarchic circles and his fame transcended so much that he was proposed as mayor of Lima by the people of Lima themselves, but he chivalrously rejected it. In less than three decades he was one of the most influential men in Peru, until luck turned its back on him and on February 24, 1928, mired in bankruptcy, he performed the seppukku rite in his Lima mansion on Quinta Heeren.

Kitsutani's most memorable administration occurred in 1921, when on behalf of the Japanese colony he took the initiative to present Peru with an immense monument commemorating the Inca Manco Cápac (according to legend he was the first governor of the Tahuantinsuyo empire). But those were times when Peru did not want to remember its indigenous origins and rather encouraged European migration.

Even today we are surprised by the confidence and audacity with which the Japanese immigrants acted to give such questioned symbols. The Japanese community had only been installed in Peru for 22 years and dared to remind Peru of its indigenous roots. The first hundred years of republican life were commemorated and the foreign colonies gave gifts to the Peruvian State that were placed in public spaces in Lima, in some way these manifested the idiosyncrasy of these human groups and their relationship with Peru. The German colony gave a tall tower with its imposing clock in the University Park. The Italian colony, a lavish Art Museum on Paseo Colón. The Chinese colony is a great source of water, absolutely European. For its part, the Japanese colony gave the aforementioned monument, which could only be delivered in 1926 and which is still preserved today in the same Plaza.

Contrary to what the Japanese immigrants expected, this gift turned out to be subversive and an insult to the ruling class of the time, which saw the country's backwardness in the image of the Indian. The ruling class did not want to have anything to do with the Andean world and everything that was not Western reminded them of the savage state that they were supposed to overcome. For better or worse, it could be understood that the intention of Kitsutani and his board, as well as the Japanese colony, was to occupy a public space in the city that housed them to feel that a part of this country also belonged to them.

Then came the world war and the climate of anti-Japanism worsened. Unfortunately, fame and fortune became dangerous matters, and for possessing a little power you could end up imprisoned in a concentration camp in the United States, Panama or Ecuador. Once again, the Japanese colony was forced to seclude itself under the cloak of silence.

Discretion, good sense and professionalism

Once the Second World War ended, the Nisei or second generation generation continued to maintain a low profile either through their own experience or through the recommendation of their parents. Their efforts this time were directed towards professionalization and, starting in the 1950s, they would stand out as academics, small merchants or businessmen, university presidents and even athletes. Wherever it was, the motto was to stay as far away from politics as possible.

However, due to the organized and vital character of the Japanese colony, it was impossible not to stand out on the public stage. In the sports area, the scandal broke out over the cyclist Teófilo Toda, who in the 1950s was denied a Peruvian passport by President Manuel Odría because he was not considered representative of Peru for a world championship in Uruguay. Sad and outrageous episode that we hope will never be repeated again with any person. Of most pleasant memory is Olga Asato and the Japanese coach Akira Kato, who revolutionized Peruvian volleyball, leading it to compete for international medals. National baseball was and continues to be a Nikkei bastion with Gerardo Maruy at the helm, in table tennis Humberto Sugimizu stood out, and in soccer there were and are many players.

It is since 1980 that members of the Nikkei colony become interested in the media and entertainment. Standing out were Alejandro Sakuda (ten years director of La República and current director of Perú Shimpo), Alfredo Kato (for decades responsible for the entertainment section of El Comercio), Julio Higashi (for many years director of a television news program), Susie Sato ( host of a television news program) or Romy Higashi, television producer, among many more.

The decade of Nikkei power

Before the 1990-2000 decade there was only one Nikkei legislator 2 . With the election of Alberto Fujimori as president of Peru, many members of the Nikkei colony are encouraged to support him either as congressmen, mayors, or occupying ministries or key positions in the government. Here are some names: Lucy Shinzato from Shimabukuro, Susana Higuchi, Samuel Matsuda, Ana Rosa Kanashiro, Daniel Hokama Tokashiki, Jaime Sobero Taira, Jaime Yoshiyama Tanaka, Josefina Takahashi, Luis Baba Nakao, Marco Miyashiro and many more.

Suddenly, television and the press were invaded by Nikkei faces on a daily basis. Without a doubt, it was the Nikkei decade in political life and none of them stopped promoting the Nikkei identity, in fact, it seemed that they flaunted and flaunted it as in the remembered 1920s. Being a Nikkei was no longer a threat, It did not subtract anything but rather added prestige.

Alberto Fujimori himself applied this same winning formula. He sold his Nikkei image as a synonym for “honesty, technology and work” 3 to obtain the votes that would consecrate him as president of the republic. After his escape and his disastrous resignation by fax as president of Peru, would it be advisable to continue raising the Nikkei identity to enter politics?

Fortunately, the Peruvian population has learned to see the Nikkei community as a sum of individuals and not the uniform and compact mass of sons and daughters of the rising sun. Currently, within the Japanese colony there is less ethnic secrecy but happily social charisma persists. Unlike before, issues such as power, fame or social recognition are assumed by the Nikkei themselves as individual and not collective issues. The awareness of transience has been replaced by territorial certainty, and expressing an opinion no longer causes fear but rather they feel that it is an obligation and a citizen's duty. Public space and power is now within reach for the Nikkei community.

Grades:

1. This was the slogan of his political party Cambio 90.

2. Juan Kawashima elected in 1979 to the Constituent Assembly, on the eve of the return to democracy.

3. Rocca Torres, Luis. The samurai spirit at Quinta Heeren . Lima: Editorial Perú Shimpo. June 2002.

© 2007 Doris Moromisato