Growing up in the 1970’s in Chicago’s near west suburbs, there were few people like me. In fact, my sister and I were the only half Japanese, half Swedish/German girls on our block (or in our community for that matter). Most people thought I was Chinese and it didn’t take long to realize that “chink” was not a friendly word. As a kid, I gravitated towards the “others”, the few kids in the neighborhood who were Puerto Rican, Mexican or who just didn’t fit in. Despite being isolated from other Japanese or other Asian Americans, I always identified more with being Japanese, probably because of my appearance and my close relationship with my mother, who was born and raised on the Big Island of Hawai’i.

In high school, my Latino and African American classmates readily accepted me and didn’t seem to care what I was. While most of my Caucasian peers were equally welcoming, many didn’t quite know what to do with me. “Is she Oriental or White?” This was clearly an issue for some. They’d ask me dumb questions and at times make racist jokes not thinking I’d be offended. I knew a girl in high school who used to call my mother “Mrs. Miyagi”. (At least she got the ethnicity right).

When I started university, I decided to study literature and began reading books by people who felt marginalized and who were starting to define themselves on their own terms. I began to meet other Asians, particularly Filipinos, and I got involved in a local Filipino theatre group, Pintig. There I met many dedicated cultural activists who inspired me with their strong sense of identity and their passionate desire to sustain their culture in the States.

My work at Pintig led to a friendship with Larry Leopoldo who shared my interest in starting an Asian American arts magazine. Over coffee in a café, we decided that the focus of our magazine would be works “by and about Asian Americans” and we named it riksha. When we put the call out for submissions, we began to realize that there were lots of people out there making their art, sharing their stories and starting to connect with each other. They all needed more exposure.

Over the next few years, riksha lived through many incarnations. Through the hard work of talented people like Larry, along with Alex Yu, Patty Cooper and Ed Eusebio (and numerous others), riksha published several magazines and held a variety of performances and exhibits in local cafes, art galleries and clubs. riksha collaborated with many organizations and helped to contribute to the dialogue that had started about what it meant to be Asian American.

Following university, I went to live in Hawai’i for a few years. I’ll never forget the first time I met some local writers/publishers. I started blathering on about the Asian American movement and they just stood there with blank expressions. “Asian American?” one of them asked (he was local Chinese). Then he just chuckled like he’d heard it all. What I later realized is that not everyone lives in a hyphenated world. And there are places, even in the States, where Asians are the majority and don’t feel the same sting of racism as on the mainland.

Of course, Hawai’i is not perfect and there are plenty of race issues to contend with there too. Just ask the Native Hawaiians. But it is a place where Japanese Americans, and other Asian Americans, have been at the top of the social hierarchy for years now and it’s also a place where hapas like me (half-White, half any other race) fit in easily. I am ordinary there and being ordinary is a welcome reprieve.

While living in Hawai’i and spending time with my aunt and uncles, I discovered more about my family history. My grandfather, Ryoji Sumida, born in Hiroshima, left Japan as a young man in the early 20th century in search of work prospects in Brazil. When his ship docked in Hawaii, he and his brother decided to stay in the islands. No doubt it reminded him of his native city (something I realized on a recent trip to Hiroshima). On the Big Island, my grandfather, who was a fisherman by trade, started a business enterprise that would grow into a general store, a fishcake factory and a restaurant, among other endeavors.

When Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, martial law was declared and it was not long before the FBI started rounding up and interrogating prominent Japanese Americans. My grandfather was detained in Hilo and only through the help of a friend, an attorney who had been living in Hilo for many years, was he released after six long months. I had the opportunity to correspond with the attorney turned judge, Martin Pence, before he died. What struck me most was his willingness to step forward at a time when loyalties were being questioned. Of course, Judge Pence didn’t think of himself as extraordinary; rather he simply felt that an injustice has occurred and he needed to do something about it. My grandfather never forgot Judge Pence’s efforts on his behalf and my mother tells the story of the delivery of “special catches of the day” to Judge Pence for years following the war. A small gesture from a grateful man.

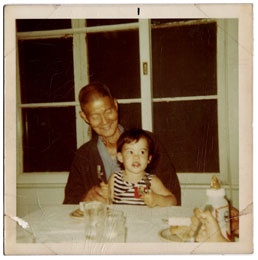

My grandfather died when I was ten years old and my memories of him are hazy now. On a shelf at home where I place special mementos, I often look at the photographs of him. One is with my 2-year old self in his lap and another is with him and several family members and employees in his general store. He was a stoic and practical man with his own children, but with us (his grandchildren), he was an altogether lighter person, quick to smile and play and who expressed his love through walks holding hands and naps curled up close. My mother told me that he would “light up” whenever my sister and I would visit him. He was a man who, despite his hardships and sacrifices, which included surviving the devastation of two tsunamis in Hilo, lived his days with a sense of gratitude and generosity that touched all who knew him.

As I became more grounded in my family history, it became somewhat easier to deal with the more prickly aspects of being Japanese. While I had read about Japan’s atrocities during the war, learning to deal with it firsthand was another story. I remember my first encounters with friends whose families had been affected by Japanese occupation. Their stories were awful and I was often stunned and shamed into silence. I could tell that they felt badly telling me but they seemed driven by a need to tell someone, someone Japanese, and to be heard. As time went on, I found myself apologizing after these encounters. Perhaps it seems odd to apologize for something so removed from my own personal experience. But somehow, it just seemed like the right thing to do.

I remember one day, when I was first dating my now husband (who is Filipino/Chinese), I met the aunt of my father-in-law who had immigrated to Chicago many years ago. She proceeded to tell me the horrific tale of her husband’s murder by imperial soldiers in the Philippines and how she was left to raise her small children on her own. The details of her story were so vivid, as if she had experienced the loss only a short time ago, and her emotions were still raw. I knew she didn’t blame me personally but she needed me to hear her and, for a moment, feel the discomfort of her tragedy. She held my hand as she told her story and I felt a small reconciliation take place. This is a burden that we Japanese carry, but it’s also an opportunity, a chance to extend our compassion and interrupt the cycle of pain that continues to this day.

After living in Hawai’i, I traveled and lived in different places and later decided to come back to Chicago. I returned to study and became a clinical social worker. I currently work with children and families in an outpatient mental health center. If I can instill just a bit of hope or offer assistance to cope with a difficult situation, well then, it’s been a good day. And what I learn from the people I’ve met only reinforces my belief in resiliency and, ultimately, gratitude for the simple things, an awareness instilled in me at a very young age by a very wise man.

Over the years, my involvement in the Asian American arts has diminished in favor of other pursuits, but I continue to support the community. The loose collective of riksha members continue to talk about what we might offer in the future. Times have changed and organizations like riksha are needed less in a world where our artists and writers know how to promote themselves in expedient ways, but we’ll keep the dialogue going and see where it takes us...

* This article was originally publised in the Voices of Chicago by the Chicago Japanese American Historical Society.

© 2007 Chicago Japanese American Historical Society