During the early years of the 20th century, Japanese immigrants to the West Coast of Canada, like their counterparts in California, found themselves the object of increasing hostility by local whites. The racial and religious difference of the immigrants, and their presence as economic competitors to white farmers and merchants, fueled the efforts of exclusion leagues and West Coast political leaders to cut off Japanese labor immigration. By 1908, in the wake of anti-Asian race riots in Vancouver, leaders in Ottawa arranged their own “gentlemen’s agreement” with Tokyo, which cut legal entry by Japanese to Canada to an annual total of 400 people (later reduced to just 150 per year).

Conversely, in faraway Quebec, where few Japanese settled in the prewar years, popular attitudes towards Japan and Japanese immigration were more neutral. The Catholic Church, the dominant institution among Quebec’s French Canadian majority, organized missionary efforts to aid and convert Japanese and other Asians. During the interwar years, a dozen French Canadian priests and nuns settled in Japan as missionaries. (Paul-Émile Léger, the future Cardinal of Montreal and “prince of the Church” in Quebec, taught in Fukuoka in the 1930s).

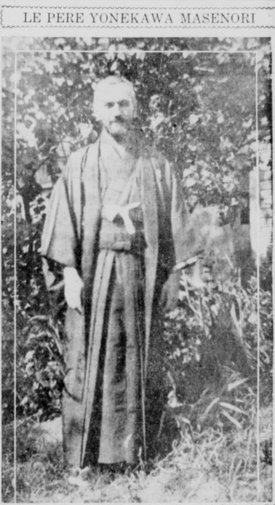

Among the missionaries was a remarkable priest, known as Father Urbain-Marie, who took the Japanese name Yonekawa. In addition to operating a mission, Yonekawa wrote books that introduced his French Canadian readers to Japan and educated them about Japanese culture. In later life Father Yonekawa would distinguish himself as a supporter of Japanese communities in Peru.

He was born Alphonse Urbain Cloutier in May 1890 in Saint Narcisse de Champlain, a small town near Trois-Rivières, Quebec. He was the oldest of eight children of Joseph Dauphin and Josephine Ledoux Cloutier—his two sisters would later become nuns and work in Asia, even as his brothers moved to different places in Canada. His parents both died when the young Alphonse was a teenager.

The youth studied at the Collège séraphique, a Franciscan school in Trois-Rivières, and the Séminaire St. Sulpice. He took his vows in 1914, and following his philosophical and theological studies in Quebec City, he was ordained in July 1917.

Following his graduation, he spent a year as professor of literature at the College séraphique. A newspaper of the period reports that Abbé Alphonse Cloutier was assigned as a priest to the College de Sainte-Thérèse, and directed a newly-opened chapel at the Canadian Pacific Railroad station in the Montreal suburb of Laval, Quebec.

In October 1918, in company with another Franciscan priest, Father Hilaire-Marie Gamache, Father Cloutier sailed to Asia to serve there as a missionary. Once arrived in Japan, he was assigned to a mission in Hokkaido. He began intensive study of Japanese language.

“After having learned the Japanese language,” he later remarked, “I came into closer contact with the people whose quite advanced civilization dates as far back as the 9th century, and I learned to love them most sincerely.”

Around the same time, he applied for Japanese citizenship. According to some sources, he felt required to take this step under Japanese law in order to open a mission. Others say he was inspired by feelings for Japan. Whatever the case, he was granted Japanese citizenship in 1923 and changed his name to Masanori Urbain-Marie Yonekawa (“masa” as in “govern,” “nori” as in Urban and “yone” as in rice or America).

In 1921, he opened a mission at Asahigawa, in the apostolic province of Kagoshima, thereby becoming the first Canadian priest to found a mission in Japan. He served there as ecclesiastical superior from 1925-27.

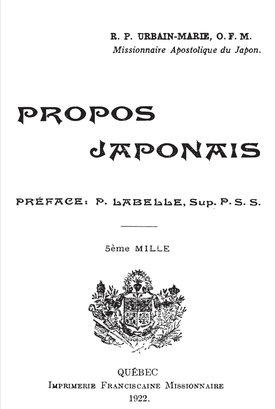

Throughout his time in Japan, Yonekawa contributed articles and columns (which he called “croquis”) on Japan to newspapers and journals in Quebec. In 1922, the year after he opened his mission, he published his first book, Propos Japonais (1922) under the name Urbain-Marie Yonekawa. It was a series of short essays grouped around the subject of Japan and Catholicism.

It was divided into five parts: “Propos de vie sociale” [Discussions of social life] covered subjects such as Japanese railroads, firefighters, and politeness. “Propos rustiques” [Rustic discussions] included Japanese villages, Catholic burials and a trip to Hiroshima (a generation before the atomic bomb devastated the area). The section “Propos Religieux” [Religious Discussions] dealt with such subjects as tolerance of Catholicism and Shinto festivals. “Propos historiques” [Historical Discussions] featured an extended section on history of Catholicism in Japan. The final section, “Propos apostoliques”

[Apostolic Discussions] examined missionary efforts and the success of the priests in converting the Japanese to Christianity. Upon publication, the book was widely and positively reviewed in the French Canadian press. Writing in La Tribune, a critic enthused: “He introduces us to Japan, he makes us travel from north to south through a series of chapters which are also paintings; from the first he captures our attention, awakens our interest, excites our curiosity; and all these things grow from chapter to chapter...until the end.”

In 1928, after ten years in Japan, Yonekawa returned to Canada. His arrival was hailed in newspapers throughout throughout the Dominion. In a number of interviews, Yonekawa stated that the goal of his visit was to recruit more French Canadian priests for work in Asia.

During his Canadian tour, he undertook a series of lectures. He spoke before the “Club La Salle” in Windsor (where he amused his audience by starting his talk in Japanese language). He then presented a pair of talks in Ottawa—one at University of Ottawa, on the Political History of Japan, the other at a convent, on the Japanese soul (complete with lantern slides). He spoke before a large gathering at the City Hall in Trois-Rivières, under patronage of the Knights of Columbus, on the history of Catholicism and the persecutions in Japan.

Not only Yonekawa’s speech, but also his Japanese-style silk clothing, were mentioned widely in press accounts. (Also mentioned was the set of Japanese objects which he brought to raffle off to raise money for the missions in Japan).

During his visit to Canada, Yonekawa extolled Japan as a fertile ground for missionary work. “Japan is marvelously well prepared for conversion to Catholicism….In a few years, Japan will be among the most Catholic countries in the universe. In my prefecture of Kagoshima, I am the lucky pastor of more than 4,000 faithful in 20 places. My faithful are very sincere and fervent.” He called Japan his new homeland, and affirmed repeatedly that he intended to return there: “I want to die in Japan.”

However, he never returned to live in Japan. One source said that he was forced by failing health to remain in Canada. He may possibly have been named persona non grata by the Japanese government. Whatever the case, he was invited to Italy to teach at the Franciscan academy at Naples.

Instead, he decided to go to Egypt, where he spent the next years in various assignments—for a time he was Vicar at the convent of the Assumption in Cairo, and then at a convent in the suburb of Bacos. In 1934, he was named chancellor of the Bishop of Alexandria, where he served for three years.

During his time in Egypt, Yonekawa wrote three further books on religion and Japanese society which were published in Europe. Âmes japonaises (1933) is a collection of life stories of Japanese converts to Christianity.

As La Revue Dominicaine, tactfully put it “Re. Yonekawa’s book, which we would only criticize for its weaknesses of style, makes us love the strange country that he brings us to look at. We remain obsessed by a ‘Japanese with a fine smile which often hides the most intense inner conflict'. But for us to love Japan means to pray for the conversion of its inhabitants…and help the missionaries who work there.”

Croquis Japonais (1933), produced for a French publisher, and Le Raffinement Japonais (1934), published in Belgium, are synthetic historical studies of Japan, including political developments, the changing status of women, art, literature, and the story of Christianity (Protestant and Catholic).

He produced two other books on Egypt during the decade. Visions Égyptiennes: Visions Profanes (1936) is an analysis of Egyptian society at the moment when the British protectorate lapsed and Egypt achieved independence. Visions Égyptiennes: visions bibliques et chrétiennes discussed the difficult circumstances for Christians in a Muslim-majority society. Another work, Dans l’Orbe de Manille (1938), produced at the time of the Eucharistic Congress, is an extensive description of politics and society in the Philippines at the close of the U.S. colonial period.

During these years, as the Sino-Japanese conflict grew more deadly, Cloutier/Yonekawa emerged as an extreme advocate for the Japanese side. While he was ostensibly motivated primarily by anti-Communism and fear of Soviet Russia, in fact his views were also flavored by racial prejudice against Chinese.

In an interview he gave to Le Devoir during a trip to Quebec in 1935, he praised Japan’s occupation of Manchuria, claiming that Japan was forced to take control of the region because China was in a barbaric state, and that Tokyo had no territorial ambitions there. He contended that Japan had no choice other than to leave the League of Nations when its policy was unjustly criticized in the report of the Lytton Commission.

Two years later, in November 1937, Yonekawa returned to Quebec to spend time with his family, and proceeded to spend several months in Canada. During this time, he resumed his defense of Tokyo’s policy in China. In February 1938, he addressed members of the Society of Conferences of Ottawa University in the Academic Hall.

According to an English-language newspaper account, he asserted that Japan was not to blame for its invasion and occupation of China: “In reality the aggressor in the present Sino-Japanese conflict is Communism. Japanese have no territorial design in China. Their only aim is to stamp out Communism, believing that in preventing China from falling under Soviet domination they are saving their own country.”

China, he insisted, was not a nation but a conglomeration of families with no geographical unity or national language. Tokyo was thus engaged in a war not of its asking, whose aim was to do away with the inroads being made in China by Communism. “Japan is the only country which is waging war against Communism outside its own territory,” he concluded. “Its action is a counter-offensive. A Sovietized Far East would be a terrible menace to the security of the whole world.” Soon after, he published a pamphlet “Le conflit Sino-Japonais,” outlining his views.

© 2024 Greg Robinson