My dear cousin Judy Mackey (Baker) passed away on February 11, 2024, at the age of 99. During her long career as an economist, she served as a role model and inspiration for many people, especially for women breaking into professional fields. I want to speak here about how she helped shape my work as a historian and scholar of Japanese Americans.

She was born Judith Rosenblum in New York in January 1925, the only child of Moses and Sophia Rosenblum, Jewish immigrants to America. During the Great Depression the family experienced hard times and took in boarders as well as working. The 1940 census listed the family as living in the Bronx, where Judy’s father was employed as an embroiderer.

Judy remained attached to the Socialist ideals her parents had carried from Europe to their adopted home, and became involved in political organizing. During World War II, Judy enrolled at Hunter College, where she obtained her BA degree.

In 1943, Judy’s beloved father Moses died. With encouragement from her mother, Judy completed college and enrolled in the graduate program in economics at Columbia University—economics was not considered a women’s profession in those days, and Judy was one of only two women in her entire class. While she completed the coursework for a Ph.D. at Columbia, she decided not to sit for her doctoral exams, and instead left school.

In 1948, at a political rally, she met John Mackey, a young sailor and union activist. Within two months of their first meeting, the pair were married. Judy accompanied her new husband to Berea, Ohio, where he attended college. Although she had been promised a job teaching economics at Case Western University, the position did not materialize.

At length Judy found a job as an elementary school teacher. (In later years, she recounted how, because of her married name Mackey, she was repeatedly asked whether she were Catholic. When the school principal found out that she was Jewish, he assured her that there was no problem—so long as she was not Catholic!).

After a year in Ohio, Judy returned to New York and looked for jobs in the economics field. Despite her credentials and support from Columbia professors, she experienced serious job discrimination as a woman. In the end she found work as a researcher, first for the National Bureau of Economic Research, and then for the Life Insurance Association of America. When she was refused a promotion at the Association on gender grounds, she decided to leave.

At a professional meeting, she ran into Alan Greenspan, who had been a fellow student and friend of hers at Columbia. Greenspan had recently become a founding partner of Townsend-Greenspan, a fledgling economic consulting firm. At a time when no other economics firm would employ a woman, Greenspan gave Judy a chance, hiring her as a statistical researcher. Judy soon rose to the position of Vice President and Treasurer of the firm.

Judy became an innovator in her field, as a specialist in what is now called behavioral economics. Going beyond official statistics, she made predictions about the economy based her research into real-world conditions. She correctly insisted there would be a baby boom in the 1950’s by noticing the figures of New York's women’s expanding waistlines. She correctly predicted a rise in consumer spending by observing that shopping center parking lots were full of cars.

An enthusiastic presenter, she accepted invitations to speak at locations where no women had previously been allowed to enter, shattering gender-based restrictions.

While John Mackey remained absent on work trips throughout much of the couple’s first years, by the end of the 1950s he and Judy were reunited. They bought a home in suburban West Nyack, NY, where in the next years they had three children: Malina, Valeda and Sean. Judy gave up her regular position at Townsend Greenspan and worked from home, caring for the children and writing an economic newsletter, the Townsend Letter.

John Mackey died in 1975, following an extended period of mental and physical health struggles.

Needing to support the family alone, Judy returned to full-time work with Townsend Greenspan, even as her mother Sophia moved into the house to help care for the family. Judy provided consulting and economic forecasting for major businesses, and traveled widely around North America sharing her expertise about the shape of the economy. When Alan Greenspan became Chair of the Council of Economic Advisors, Judy joined in meetings at the Oval Office with President Gerald Ford—she proudly hung photos of the meeting group on the wall of her house.

In 1978, Judy met and married Russell Baker, a fellow economist. Her second marriage was as happy as the first had been troubled. After a few years together, the couple moved to Williamsburg, VA.

At first, Judy commuted to work at Townsend Greenspan. However, in 1987 Alan Greenspan was appointed Chairman of the Federal Reserve by President Ronald Reagan. The Townsend-Greenspan firm closed down, and Judy officially retired. Seeking both extra money and occupation, Judy and Russ together started their own economic consulting firm, Mackey-Baker Associates. The couple worked together writing a monthly newsletter, Commentary, for their clients.

In the years after 2000, Russell Baker became ill and the couple closed their firm and relocated to Denver, Colorado, where Judy’s children resided. After Russ’ death in 2007, Judy took up a new life, mixing education and cultural activities, and being a close, loving presence in the lives of her three children and five grandchildren.

I felt connected to Judy from my early childhood, the more so as her children were my closest relatives and favored playmates, and she followed my educational development with pleasure and pride. When I turned to the study of Japanese American history, Judy contributed to my work in many different ways. She faithfully read the articles I sent her and publicized my books with her friends.

When I visited her in Denver, she drove me to research interviews and archives, and attended my lectures and conference appearances. (Judy liked to tease me about the time in 2008 that she took me to the JANM conference in downtown Denver. As I walked into the hall, I was immediately surrounded by conference goers who knew me from my newspaper columns and my frequent visits to the museum. A woman behind the registration desk remarked to Judy, “I bet you didn’t know that your cousin was a rock star!”).

When I began research on the Nisei journalist Larry Tajiri, Judy stepped in as my research assistant. While Tajiri was most renowned as editor-in-chief of the the JACL newspaper Pacific Citizen during the World War II years and the postwar era, he actually spent the last decade of his life in Denver as entertainment columnist and critic for The Denver Post.

For several weeks, Judy went down regularly to the Central branch of the Denver Public Library and painstakingly went through the microfilm holdings of The Post, seeking out and copying Tajiri’s entertainment columns and his obituary. (It was fascinating to discover a warm memorial tribute to Tajiri in its pages by the independent journalist James Omura, the arch-opponent of the JACL.)

Undoubtedly Judy’s most important gift to me came in the realm of analysis. Even as she had introduced “behavioural economics” in forecasting trends in the economy, she reminded me to keep real-world considerations in my thinking. When I first began my research into the causes behind the mass removal of West Coast Japanese Americans and Franklin Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066, I spoke to Judy about my confusion over the roots of the President’s decision to sign the order, and the nature of the political pressures on him. Like the trained economist she was, Judy said, “If you want to know why people do things, follow the money!”

It was then that I resolved to look at the economic self-interest of the West Coast farmer and commercial groups in pressing for removal of the Issei, who were their economic competitors. I had already read Morton Grodzins’ groundbreaking 1949 study Americans Betrayed, which spoke about the central role of economic and nativist pressure groups in California in lobbying for mass removal.

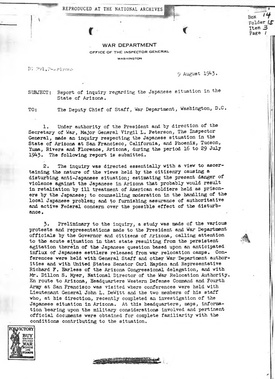

It was Judy’s insight that led me to examine the actions of the Army and the War Department, which were supposed to be insulated from economic and political pressure groups. It was then that I discovered a notable case of “follow the money”—how pressure from politicians and economic groups led the War Department to change its policy to assist Japanese Americans in wartime Arizona.

During the first decades of the 20th century, the state of Arizona was notorious for anti-Japanese prejudice. The state enacted an alien and law in 1921 to discourage settlement by Japanese aliens and their families. In 1934-35, white farmers in the Salt River Valley gained nationwide publicity by organizing a “crusade” whose members used threats and terrorism to drive out Japanese American families.

In the weeks after the outbreak of the Pacific War, newspapers and public speakers in Arizona overwhelmingly supported mass removal and confinement of the state’s ethnic Japanese population. The War Department included the entire southern half of Arizona as part of Military Area 1, from which all ethnic Japanese were subject to exclusion.

Although Arizona lay far distant from the Pacific Coast, and the threat of Japanese invasion that ostensibly made removal necessary to avert was equally remote, Arizona governor Sidney Osborn and other state political leaders pressed the War Department to ensure the emptying of the state’s southern half, closer to the Mexican border.

The mass removal from the West Coast brought some 35,000 Japanese Americans to Arizona for incarceration. The War Relocation Authority created two camps, Colorado River (AKA Poston) and Gila River, to hold these Japanese Americans. Even as Japanese Americans languished in the camps, much of the long staple cotton grown in Arizona remained unpicked in the fields because of labor shortages. The War Department was anxious to have this cotton conserved, and arranged with the WRA to recruit volunteer laborers on temporary leave from the Gila River camp, who would be brought to the fields under military guard.

Japanese Americans did not like the work of picking cotton under the conditions offered them. Only a very small number, less than 300 in total, volunteered for the work. Local farmers’ urgent need for labor outweighed their hostility to Japanese Americans, and they contacted their representatives.

On or about January 20, I943, the entire Congressional delegation from Arizona sent a letter to Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, imploring him to alter the exclusion lines southward to place the cotton fields outside the excluded zone, so that inmates recruited from the camps in Arizona could work picking cotton without military guard. On March 2, 1943, the Western Defense Command and Fourth Army issued Public Proclamation No. 16, which moved the exclusion line in Arizona southward so as to exclude from the restricted zone almost all of the cotton lands of Arizona. In fact, after the harvest, the border of the excluded zone was once again redrawn northward.

I was able to see my cousin Judy one last time before her passing. In January 2024, after I attended a conference in San Francisco, I stopped by Denver on my way back East. Judy was in hospice care in an assisted living facility. Her children told me that she was declining, and she might sleep through my visit.

To my great relief, however, she was awake and fully conscious when I arrived. I gave her my author copy of my just-published new book, The Unknown Great. She looked it over eagerly and said she would read it and share it with her children. We chatted for about 30 minutes, covering the usual family and professional things, then she said she needed to nap some more, and I left.

I will always remember her and be grateful for the help and support she gave me.

© 2024 Greg Robinson