Shaun Shimizu lives in two worlds. In one world, he’s an American Sign Language interpreter, both personally and now professionally. Shimizu, who grew up as the only Hard of Hearing person in his Deaf family, has been interpreting as long as he can remember.

In the second world, Shimizu was born hearing and became Hard of Hearing by the age of 5, attending speech therapy between classes and occasionally on the weekends. His life is in constant flux between those two worlds.

While attending Pearl City High School, Shimizu said he was enrolled in a class called Special Ed, but it was renamed the Deaf and Hard of Hearing program, noting how the language evolved since graduating in 2004.

Over time, “Deaf” and “Hard of Hearing” have changed in its usage and how members of the community identify. Carol Padden and Tom Humphries stated in their book Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture, deaf with a lowercase d refers to “the audiological condition of not hearing,” while the capital D “Deaf” denotes a “particular group of deaf people who share language — American Sign Language (ASL) and a culture, and like many other cultures in the traditional sense of the term, historically created and actively transmitted across generations.”

According to the National Association of the Deaf (NAD), the phrase “hearing-impaired” was once viewed as politically correct but is no longer accepted by most of the community because “impaired” focuses on what a person cannot do. “Hearing-impaired” establishes hearing as the standard and anything different as substandard, implying that something is not as it should be.

The NAD website’s FAQ’s page stresses the importance of words and labels and when in doubt, asking the individual how they identify. “We may be different,” the website states, “but we are not less.”

Shimizu identifies as Hard of Hearing, with capital letters, and acknowledges the balancing act of living in both worlds.

“To this day, I still feel like an outcast,” said Shimizu. “I still call myself the black sheep of the family. I meet with a lot of hearing kids with Deaf parents, and they call themselves CODA, Child of Deaf Adult. I don’t feel like I meet that standard of how they grew up because I lost my hearing, too. And then I also don’t feel heavily involved with the Deaf kids because even though ASL is my first language and I have a Deaf family, I can hear. They say, ‘you can still hear and you can talk clearly, people can understand you,’” Shimizu explained. “So I’m stuck in the middle.”

He notes that growing up in Hawai‘i, where the pool is already small, the Deaf community is even smaller, where “everyone knows everyone.” Even so, he rarely met someone in the same situation as him — Hard of Hearing in a Deaf family.

To be Hard of Hearing in a hearing world can be an invisible struggle, since a person doesn’t “look” Hard of Hearing or Deaf. Since he speaks clearly — though Shimizu said he struggles occasionally with the “s” and “z” sounds — he sometimes is faced with people who think he’s ignoring them when in reality, though he wears a hearing aid and can read lips, he said he just can’t hear everything.

In contrast, being Hard of Hearing in a Deaf world means that Shimizu is the family interpreter, and said he’s been “interpreting forever.” ASL was naturally ingrained in his upbringing, and his mother said as a baby, he was signing more than talking.

His grandparents, who are hearing, conversed with Shimizu frequently, and he credits his grandmother for developing his vocabulary and encouraging extra speech therapy classes.

Many childhood nights were spent at his grandparents’ house in Hawai‘i Kai and Shimizu would listen to his grandparents and sign their words to his parents and sisters, then read their responses and translate back. “My grandmother learned a little bit,” said Shimizu of learning ASL. “She did a lot of fingerspelling, but most of the time, my sisters would say, ‘you have to interpret.’”

His grandparents, like many families with Deaf members, utilized a “home sign,” or a basic sign language. “My grandparents developed a real basic home sign — gestures like ‘you want to eat?’” said Shimizu, demonstrating spooning food into his mouth. “Or ‘you want to go home?’” He pressed his fingers together in an inverted triangle to symbolize the pitched roof of a house.

“Real simple signs. But when they wanted to have a full-on conversation, that’s when I came into the picture.”

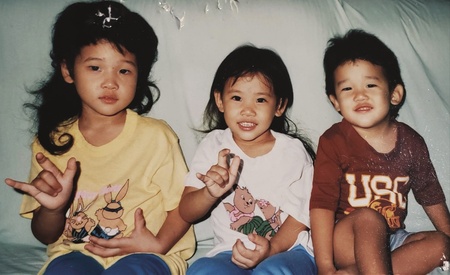

Shimizu is part of one of the largest Deaf families in Hawai‘i — his parents, Gail Nakahara and Stanford Shimizu, and two older sisters, Shana and Sherry, are Deaf. On his dad’s side, an uncle and three cousins are Deaf, and on his mom’s side, an uncle and two cousins are Deaf.

During holidays or if he’s given a head’s up that hearing people will be at a family meeting, Shimizu said he would ask a friend to come along and interpret, (and he’d serve as a backup) so he could be more involved or engaged with family.

“If you’re interpreting for a family member, you get emotionally involved and kind of just forget about interpreting, and talk,” said Shimizu. “I have to remember to come back to my role and interpret for my family because they don’t understand what people are saying.”

The ethics of an interpreter is to remain neutral and impartial, and Shimizu shared that it’s harder to socialize when he’s both an interpreter and participant, because as an interpreter, he’s trying to keep a boundary.

“If I interpret for people I hang out or I socialize with, it kind of feels awkward,” Shimizu explained. “Because if I interpret for their medical appointment, I think they feel awkward, and I don’t want to make them feel more awkward.”

But, however uncomfortable interpreting a mammogram appointment may be, Shimizu said he would do anything for his godmother, who he said basically raised him after his parents divorced. “We’re not blood related, but anything for her, I will do. I could say she’s one of my heroes,” he said. “She teaches me stuff about life, basically everything. Once I got my license, I was always at her house.”

His godparents, Michele and John Mekaru, are Deaf and live nearby. Shimizu interprets for them frequently, and he’s happy to help and tries to see them as much as he can. “They communicate really well with my son,” he added.

Part of the reason Shimizu started working at Hawai‘i Interpreting Services is because he felt it was time to come back to the Deaf community after working different jobs. Shimizu has been the office manager at Hawai‘i Interpreting Services since 2018 and enjoys coordinating schedules and placing interpreters with Deaf, Hard of Hearing, or Deaf-Blind clients who need assistance. Oftentimes, Shimizu will take ASL interpreting jobs as well and is one of the 40-plus interpreters spread out across the islands.

Hawai‘i Interpreting Services is a female-owned minority small business, established by Sabina Wilford and Judy Coryell in 2007. The company’s mission is client driven and committed to “providing equitable communication for the Deaf/Hard of Hearing/Deaf-Blind so that they receive the equal access that they are entitled to.” The company is known for its high standards and offers ASL Interpreting, Deaf-Blind, Real-Time Captioning (CART), or Computer Assisted Note-Taking (CAN).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Shimizu said services slowed in the beginning due to lack of in-person connection, but they were able to utilize video remote interpreting through mechanisms like Zoom and Google Meet to help people communicate. They also use a videophone, which Shimizu described as a very large phone, almost like a webcam but with its own phone number and runs on WiFi. Video, he said, makes it easier to communicate so they can sign faster instead of typing or emailing things out.

Following the Maui fires, Shimizu said Maui interpreters are on the ground going from shelter to shelter to see if people in the Deaf community needed interpreting.

*This article was originally published in The Hawai‘i Herald on September 14, 2023.

© 2023 Summer Nakaishi