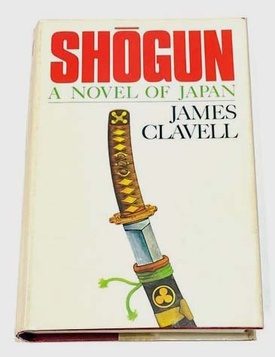

The late author and screenwriter James Clavell is best remembered these days for his series of bestselling novels set in Asia, most notably the 1975 epic Shogun. A sprawling fictionalized account of the origins of the Tokugawa regime, it recounted the adventures of John Blackthorne, an English mariner shipwrecked in Japan. In 1980, Shogun was adapted into a hit television miniseries starring Richard Chamberlain and Toshiro Mifune, with Clavell serving as executive producer.

Shogun helped introduce a generation of white Americans to classical Japanese history and language (unlike in Clavell’s novel, the creators of the miniseries boldly chose not to use subtitles to translate the dialogue of its Japanese characters, so it well dramatized the culture shock and incomprehension experienced by its exiled hero). Yet even before Shogun, James Clavell was active in multiple film projects that featured Nikkei from both sides of the Pacific Ocean.

James Clavell was born Charles Edmund Clavell in Sydney, Australia on October 10, 1921, the son of Richard Clavell, a British Royal Navy officer. His parents returned with him to England soon after. The young Clavell was educated at Portsmouth Grammar School, but when World War II broke out, he joined the military. Clavell’s eyesight kept him out of the Navy and the Air Force so he joined the Royal Artillery, and was commissioned a captain.

In 1941, following the outbreak of the Pacific War, he was sent to Singapore to defend the then-British colony against the Japanese. The boat carrying Clavell was sunk by the Japanese before arriving in Singapore, and he landed in Java, where he was captured soon after by the Japanese military. Clavell spent the remainder of the war years as a Prisoner of War at Changi prison in Singapore.

The prisoners at Changi faced poor food and living conditions and torture by their Japanese captors—Clavell was one of a small fraction of the POWs that survived. As an obituary in The Guardian later noted, Clavell never publicly discussed how his wartime experiences might have scarred him, but he was ruthless in ensuring that he kept total control of his extraordinary career. Clavell would later use his wartime experience at Changi as the basis of his bestselling novel and film King Rat.

After the end of the war, he moved to England and worked as a film distributor. In 1949 he married actress April Stride. Two years later, the couple moved to the United States, eventually settling in Hollywood, where Clavell tried his hand as a screenwriter and hoped to direct films. His first success came when he was hired to write the script for the classic 1958 sci-fi/horror film The Fly. Shortly after, he provided the script for Watusi, an adventure film based in Africa.

In 1959 Clavell submitted a script to film executive Robert L. Lippert’s production company Associated Producers. Lippert then selected Clavell to direct the film. The product, Five Gates To Hell, was a lurid tale of sexual violence set during the French Indochina war. An international corps of doctors and nurses working at a field hospital in Vietnam are taken captive by Communist guerrillas, who intend to push the women into sex slavery as “spoils of war.” The nurses then plan a revolt and make their escape.

Five Gates To Hell trafficked in racist stereotypes of savage orientals raping white women—especially the main villain, Chan Pamok, portrayed by white actor Neville Brand in modified yellowface. The film did at least boast a majority female cast, and provided a meaty secondary role for Canadian-born Nisei actress Nobu McCarthy as a Japanese nurse, as well as smaller parts for ethnic Asian actresses Linda Wong and Greta Chi. (Benson Fong, who would shine afterwards in the film musical Flower Drum Song, played a supporting role).

When the film made a modest success at the box office, Clavell embarked on his next project, Walk Like a Dragon, a multicultural take on the Hollywood Western. Set in California in the 1870s, it tells the story of a white cowboy, Linc (played by Jack Lord of Hawaii Five-O fame).

Linc buys a Chinese immigrant woman, Kim Sung (played by Nobu McCarthy) to save her from a life of forced prostitution. The two fall in love, and Linc asks Kim Sung to marry him, despite the abiding prejudice against interracial couples (and the fact that Kim is still legally the slave of Linc). However, Linc is also claimed by a Chinese immigrant, Cheng Lu (portrayed by James Shigeta), who asks to buy her to be his slave, but lacks the money. He challenges Linc to a duel for her, and studies gunfighting in order to prevail. In the end, the two men invite Kim Sung to decide “freely” who will be her mate. Kim Sung sees Cheng Lu as a truly equal partner, but does not wish to return to China with him. When he has her cut off his queue, representing his liberation as a Western man, she chooses him.

Walk Like a Dragon is a complex film, progressive for its time in certain respects. The film gives the Chinese woman Kim Sung agency, and it is the the Asian man, not the white, who ends up “getting the girl.” Also, the Chinese characters speak standard English, without clichéd “oriental” accents. At the same time, the film’s portrayal of Kim Sung (beyond having a name that sounds like that of the dictator of North Korea!) as submissive is heavily gendered.

Indeed, one can argue that the film (literally) builds on the “white savior” narrative trope that was common in the period: It is Linc who liberates a Chinese woman from sexual slavery, then graciously surrenders her to Cheng Lu. In fact, the ending may have been devised to skirt Hollywood Production Code restrictions on portraying interracial marriage, which still remained in force three years after Joshua Logan’s Sayonara.

Walk Like a Dragon was greeted by largely negative reviews, and did not make a success a the box office. Clavell then tried producing for television, but a pair of pilots he financed with his own money failed to sell. A screenwriters' strike in 1960 left him idle for 12 weeks, during which he wrote his first novel, King Rat, a fictionalized account of his wartime imprisonment at Changi prison that centers on the experiences of a British RAF officer and an American enlisted man (the King Rat of the title). Published in 1962, the novel became an immediate best-seller.

Even as he began his literary career at the outset of the 1960s, Clavell signed a two-picture deal with Commonwealth Film Productions, a fledgling production company based in Vancouver, British Columbia. and directed by a Czech immigrant, Oldřich Václavek. Clavell’s first film for Commonwealth, The Sweet and the Bitter, was filmed under his direction in 1962.

His screenplay, based on a story by Ernie Perrault, is by turns melodramatic and insightful. It begins with Mary Ota (played by actress Yoko Tani) returning to Canada from Japan, where she had gone as a girl with her mother. She is determined to find the businessman Duncan MacRoy (Torin Thatcher), whom she believes to have stolen the fishing boats her father left behind during mass removal. Mary has come to Canada as a picture bride, and has agreed to marry Dick Kazanami (Dale Ishimoto) a fisherman who lives in Steveston, the Nikkei fishing community near Vancouver.

However, when Mary learns that Kazanami is middle-aged, she flees from Steveston. Mary tracks down MacRoy through his son Rob, whom she wishes to seduce in revenge. MacRoy admits his deed, but also reveals that Mary’s mother had been his mistress before the war. Meanwhile, Kazanami appears. Mary is shocked to discover that he is in fact her father, who is living under another man’s name. In the end, Mary decides to remain in Canada and marry Rob.

The Sweet and the Bitter (AKA Savage Justice) was filmed at Hollyburn Studios in West Vancouver. It was one of the first sound films made in Canada. Although Clavell enjoyed life in Vancouver, and bought a house in the city, he later spoke about the film with regret, stating that making it was a negative experience, and lamenting that he was never paid his full salary for his work. He never made another film for Commonwealth.

Even before it was completed, business conflict arose over the film. In the end, it was put on the shelf, and not released until 1967. Upon its screening, it was widely panned as a laboriously contrived melodrama, with cliche dialogue and implausible coincidences. Both Vancouver Sun critic Les Wedman and writer Lorne Parton, writing in The Province, called it the worst film of the year. To be sure, The Sweet and the Bitter is by no means a great or even good film. However, like the 1960 Hollywood film Hell to Eternity, it was ahead of its time in addressing the wartime confinement and dispossession of Japanese in North America, and in dramatizing the agency of ethnic Japanese women.

By the time that The Sweet and the Bitter was released, Clavell had attained a top level of success. He produced his most famous screenplay for the hit 1963 picture The Great Escape. Two years later, he adapted King Rat into a popular film that he directed, starring George Segal, Denholm Elliott, James Fox and John Mills. Clavell achieved the peak of success in films as writer-director-producer of the 1967 film To Sir With Love, starring Sidney Poitier as a teacher of students in a working-class neighborhood in England.

During this period, however, Clavell turned his main attention to writing novels about Asia. Following the success of King Rat, Clavell published Tai-pan (1966), an epic about the European and American traders who established themselves in Hong Kong after the British takeover in the 1840s. Shogun followed in 1975. Clavell also wrote the bestselling novels Noble House (1981); Whirlwind (1986); and Gai-Jin (1993). His books sold some 21 million copies.

James Clavell was a gifted writer and creative artist. More than that, he had the strength of character to survive his brutal wartime experience in a Japanese internment camp and to emerge with respect and affection for Japanese, and clearly a fellow feeling with Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians who had been unjustly confined by their own government.

In 1979, following the success of Shogun, Clavell donated $10,000 to establish the American-Japanese National Literary Award. It offered a trophy and an annual $1,000 prize for short stories by Japanese American or Canadian writers that were “reflective of Japanese experiences in the Americas.” Clavell remarked, “Because I am a writer and because I have benefitted greatly from my association with Japanese and Japanese Americans, establishing this is my way of repaying the community.”

Clavell noted, “The history of Nikkei in America is one rich in culture and experiences. However, there is little time left to capture the stories of the early years. The Issei and many of the Nisei are passing away, The younger Japanese Americans will have to document the experiences of their parents and grandparents. I hope this award will inspire them to seek out these experiences from their elders before it is too late. The Nisei have their own experiences to write and make an important contribution to Japanese American history.” Past winners of the award include David Mas Masumoto, Ruth Sasaki, and Julie Shikeguni.

James Clavell died in 1994 in Vevey, Switzerland. His novels, and a number of the films to which he contributed, especially Shogun, remain important artifacts of North American culture. His films enlisted the talents of Issei and Nisei actors, and made attempts to explore and valorize the experience of Asian Americans. When he achieved success as a novelist, he sought to encourage Japanese Americans to tell their own stories.

*A new TV adaptation of James Clavell’s Shogun will premiere on FX this season.

© 2023 Greg Robinson