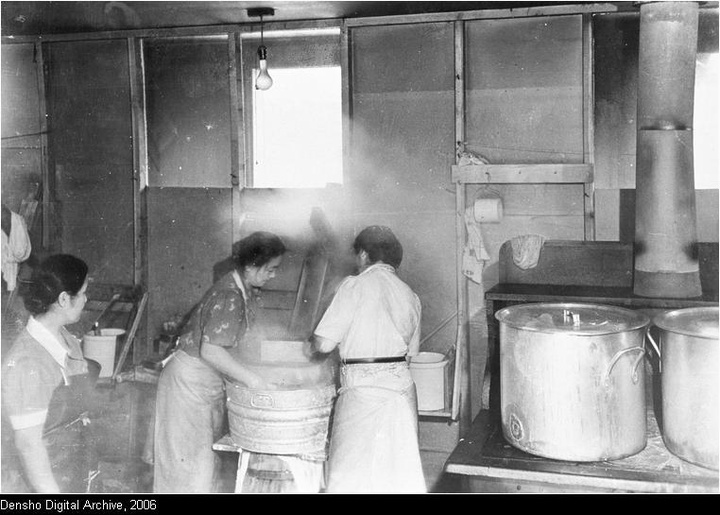

Shown above is a photo of women carrying out domestic work (i.e. laundry, cooking) at the Minidoka concentration camp in 1943, where Cherry Kinoshita was interned. Analysis of the Japanese American experience starting from the Issei reveals the kinds of gender roles that were ascribed from the very beginning to promote assimilation into American society.

That is, in adopting the American way of life to become accepted within their new country, Japanese Americans needed to prove themselves as worthy, non-inferior people of color. Culturally-related activities, such as folk dancing, tea ceremony, or flower arrangement were reserved for women, while men participated in matters of politics and state (179). Additionally, to be perceived by white American society as acceptable, women were groomed to be quiet, domestic, and obedient according to American middle-class standards. They were often even exotified as possessing such qualities, and used for the benefit of the community in its entirety.

While women stayed in the domestic sphere, as Azuma states, “their husbands tackled the more public dimension of racial politics, like propaganda, court battles, and economic struggles” (8). These gender roles continued most visibly into the Redress and Reparations era.

Japanese American men had been elected into political offices on both local and national levels, while women in the community stayed behind to take care of matters on a more grassroots level. Presidents of organizations like the Japanese American Citizens League and the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations at the time were men as well, and women did the letter sending, participated in lobbying, and stayed away from the limelight most of the time.

But this combination of Japanese American culture/values, and the need for first generation Japanese immigrants to assimilate into American society dictated this situation for both men and women. In looking at the experiences and works of Sox Kitashima, Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig, Cherry Kinoshita, and Lorraine Bannai, we can both see the gender-affected roles each played in the Redress/Reparations movement and the effects of generational influences on the types of work carried out in the campaign.

Source: Azuma, Eiichiro, Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Photo: Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Wing Luke Asian Museum Collection.

--

Shown above is a photo of women carrying out domestic work (i.e. laundry, cooking) at the Minidoka concentration camp in 1943, where Cherry Kinoshita was interned. Analysis of the Japanese American experience starting from the Issei reveals the kinds of gender roles that were ascribed from the very beginning to promote assimilation into American society.

That is, in adopting the American way of life to become accepted within their new country, Japanese Americans needed to prove themselves as worthy, non-inferior people of color. Culturally-related activities, such as folk dancing, tea ceremony, or flower arrangement were reserved for women, while men participated in matters of politics and state (179). Additionally, to be perceived by white American society as acceptable, women were groomed to be quiet, domestic, and obedient according to American middle-class standards. They were often even exotified as possessing such qualities, and used for the benefit of the community in its entirety.

While women stayed in the domestic sphere, as Azuma states, “their husbands tackled the more public dimension of racial politics, like propaganda, court battles, and economic struggles” (8). These gender roles continued most visibly into the Redress and Reparations era.

Japanese American men had been elected into political offices on both local and national levels, while women in the community stayed behind to take care of matters on a more grassroots level. Presidents of organizations like the Japanese American Citizens League and the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations at the time were men as well, and women did the letter sending, participated in lobbying, and stayed away from the limelight most of the time.

But this combination of Japanese American culture/values, and the need for first generation Japanese immigrants to assimilate into American society dictated this situation for both men and women. In looking at the experiences and works of Sox Kitashima, Aiko Yoshinaga Herzig, Cherry Kinoshita, and Lorraine Bannai, we can both see the gender-affected roles each played in the Redress/Reparations movement and the effects of generational influences on the types of work carried out in the campaign.

Source: Azuma, Eiichiro, Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Photo: Sources: Densho Digital Archive, http://archive.densho.org/main.aspx. Photo/Document Collections: Wing Luke Asian Museum Collection.