The Japanese American National Museum (JANM) has acquired Pledge of Allegiance, a seminal artwork by Na Omi Judy Shintani, for its permanent collection. The piece will be prominently featured in JANM’s newly renovated Pavilion as part of its core exhibition, In The Future We Call Now: Realities of Racism, Dreams of Democracy, when the museum reopens in 2026.

Pledge of Allegiance embodies Shintani’s unique approach to storytelling through material, memory, and symbolism. Constructed from salvaged wood collected from the ruins of a World War II-era barrack at the Tule Lake concentration camp where her father was incarcerated as a teenager, the piece forms an American flag, bound together with rusted barbed wire gathered near her current home.

The flag’s reversed orientation evokes a powerful message of reckoning with American ideals and their contradiction in history. The work serves not only as a personal reflection but also a communal elegy rooted in family memory, yet resonating far beyond it.

About the Artist

Na Omi Judy Shintani is a multidisciplinary artist, cultural storyteller, and activist whose work examines intergenerational memory, identity, and the act of remembrance. Based in Half Moon Bay, California, she has held over ten solo exhibitions and participated in countless group shows, winning awards for her nuanced and thought-provoking visual narratives. Her creative efforts extend into education, curation, and public engagement, with a consistent focus on honoring marginalized histories and bringing communities into conversation.

Shintani is a member of several artist collectives, including the Asian American Women Artists Association (AAWAA), Women Eco Artist Directory, and Northern California Women’s Caucus for Art. She is a founding member of Sansei Granddaughters’ Journey, a collective of Japanese American women artists whose work centers around the WWII incarceration experience and its intergenerational impacts.

Born in 1958 in Ames, Iowa, Shintani is the eldest of four children born to Nisei parents—her father from Washington State and her mother from Hawai‘i. The family moved to Lodi, California, when she was an infant. Her mother became the first Japanese American teacher in the local school district, while her father worked in broadcasting. Shintani recalls the values instilled by her parents—importance of education, privacy, restraint, and centrality of family—that both enriched and complicated her experience as a Japanese American growing up in postwar America.

Her mother enrolled her in art classes at an early age to channel her abundant energy, sparking a lifelong love of creative expression. Shintani studied graphic design at San Jose State University and went on to a successful 25-year career in marketing and communications at high-tech firms, including Atari and Intel.

However, a desire to more deeply explore her identity and cultural heritage led her to leave corporate life and pursue a Master of Arts degree in Arts and Consciousness at John F. Kennedy University in Berkeley, California. There, she immersed herself in the relationship between personal experience, collective history, community engagement, and the artistic process. Her graduate thesis culminated in a solo exhibition that set the tone for her career as a socially engaged artist.

Artistic Practice and Themes

Shintani describes herself as a “narrator of cultural history through visual storytelling.” Her work is deeply rooted in personal memory, yet its resonance extends far beyond the individual—shedding light on the collective experiences of trauma, survival, and resilience within marginalized communities.

Her artistic process often begins with a thoughtful exploration of her Japanese American ancestry and family history, using this as a foundation to bridge personal narrative with broader socio-political contexts. Through this lens, Shintani connects the threads of her own heritage to the lived experiences of other historically marginalized groups, creating a powerful dialogue that challenges historical erasure and fosters cultural remembrance.

Key themes in her work include intergenerational memory and inherited trauma, the dissection and reconstruction of cultural identity, community resilience in the face of injustice, as well as the tension between national belonging and exclusion.

Shintani works across various media—sculpture, installation, textiles, and found objects. These materials serve not only as physical components but also vessels of memory and emotion, evoking a sense of intimacy, nostalgia, and connection to both personal and collective histories. Through this sensory-rich approach, Shintani navigates the complex interplay between vulnerability and resilience, and poignantly juxtaposes personal tenderness with the enduring scars of cultural and historical brutality, creating spaces that invite reflection, mourning, and quiet resistance.

Selected Works

Deconstructed Kimono Series (2012–)

In this ongoing body of work, Shintani alters traditional kimonos by cutting, fraying, and reconstructing them. The act of cutting, she explains, is a meditative tribute to the community of women—mothers, grandmothers, and ancestors—who sewed and mended clothing. Yet, this process also becomes a metaphor for the erosion of cultural heritage through simulation.

The reconstructed garments reflect both her evolving relationship to ancestry and culture, and a conscious unthreading of the stereotypes often placed on Japanese American women. It also simultaneously mourns the intangible loss of tradition through its reproduction in simulated forms.

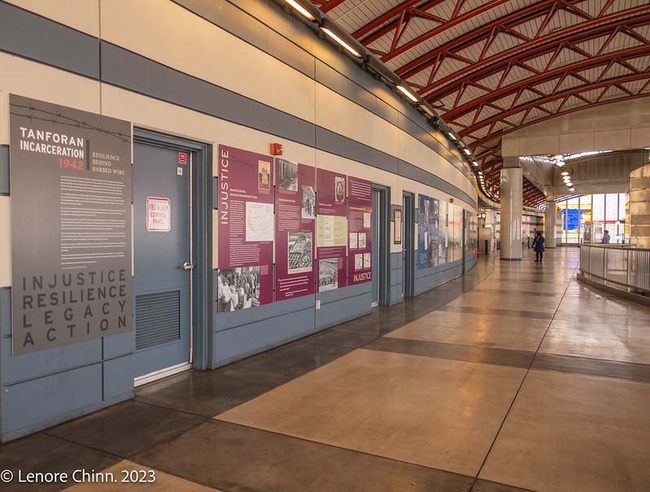

Tanforan Incarceration 1942: Resilience Behind Barbed Wire (2022)

Shintani curated this permanent exhibition at the plaza of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) station in San Bruno, California. It features historical and contemporary artworks that tell the story of Tanforan, a former racetrack turned temporary incarceration site for Japanese Americans in 1942. The exhibition includes both artwork created by incarcerees and new pieces by their descendants. Through this work, Shintani affirms the power of collective remembrance and public art to reclaim erased histories.

Dream Refuge for Children Imprisoned (2022)

This installation, titled Dream Refuge, consists of 13 child-sized cots arranged in a circle, each with life-size drawings of sleeping children. Additional drawings of children lie huddled on the floor. The project began as a response to the artist’s own family history—her father was one of the Japanese American children incarcerated during WWII—and expanded to include figures of Native American children forced into boarding schools and Central American children detained at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Each child’s clothing bears a symbolic motif: the four directions for Native children, crosses for Central American children, and embroidered details for Japanese American children. The title Dream Refuge evokes both a place of sanctuary and the fragile dreams of children caught in systems of displacement and trauma. The installation creates a solemn space of mourning, compassion, and protest.

Pledge of Allegiance (2014)

This powerful piece was born from a pilgrimage Shintani took with her father to the Tule Lake National Monument. While there, she discovered the remains of a decaying barrack from the incarceration site. As she and her father tore away pieces of wood to take home, Shintani recalls witnessing an unexpected eruption of anger in him—an emotional moment that stayed with her long after the visit.

After more than two years of contemplation, Shintani conceived the idea to use these salvaged fragments to build an American flag. She wove the wood pieces together with rusted barbed wire from Half Moon Bay, creating a visceral contrast between patriotism and persecution. The reversed orientation of the flag speaks to injustice and historical amnesia. An extra star etched into the flag acknowledges Hawai‘i, her mother’s birthplace.

The power of the piece lies in its intricate layering of personal and collective memory. It is, at once, a deeply intimate reflection and a broader cultural reckoning. Shintani draws from her Japanese American heritage, weaving in the legacy of her father’s personal trauma—scars left by his incarceration during a dark chapter of American history. This familial pain becomes a vessel for exploring the larger, often unspoken, grief carried by the Japanese American community.

At the same time, the work boldly reimagines national symbols, challenging the viewer to confront uncomfortable truths. It becomes a subtle yet urgent call for historical recognition and accountability, asking us to reconsider the narratives we uphold and those we have chosen to forget.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Remembrance

Na Omi Judy Shintani’s work stands at the intersection of art, activism, and cultural memory. Through her use of found materials, intimate family stories, and community collaboration, she crafts spaces of reflection and recognition—spaces where silenced histories are honored and made visible.

Her art invites us not only to remember the past, but to engage with it actively—to see its echoes in the present and ask how we move forward with greater awareness, empathy, and justice. Whether through the quiet resilience of a deconstructed kimono, the haunting innocence of a sleeping child, or the raw textures of a flag made from remnants of a prison building, Shintani reminds us that art is a vessel for truth —and that healing begins with remembrance.

Shintani wants her art to create an aesthetically beautiful, quiet place for viewers to ponder and understand cultural history. In her hands, art becomes both a mirror and a bridge—a way to honor what was, confront what is, and imagine what could be. Shintani’s legacy is one of reclaiming memory, voice, identity, —and the stories that shape us all. Through her work, we are invited to see the fragments of history not as relics of the past, but as pieces of a larger story still being written.

This article is based on Na Omi Judy Shintani’s own website, writing, and recorded interviews, as well as the author’s conversation with the artist.

© 2025 Masako Shinn