In high school Stacey Hayashi, 49, remembahs reading just one tiny paragraph in her textbook about Japanese American Internment during WWII. Wuzn’t till she went college at UH [The University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa] that she wen go learn much more about da Japanese American experience when she wen go take Dennis Ogawa’s American Studies 310: Japanese Americans and Franklin Odo’s Ethnic Studies 330: Japanese in Hawai‘i. Although she nevah realize ’em at da time, Stacey credits these classes for laying da foundation for what wuz going become her life’s work.

* * * * *

Lee Tonouchi (LT): What school you went? What year you grad?

Stacey Hayashi (SH): Mililani, ’93.

LT: You know my cousin Kathy Taira?

SH: That’s my classmate!

LT: Das Hawai‘i; we all know each oddahs. What your ethnic backgrounds?

SH: Yonsei, Japanese.

LT: How you identify as? Local Japanese? Japanese American? Nikkei?

SH: I just say AJA [American of Japanese Ancestry] because that’s what the vets say.

LT: What your fondest Mililani memory?

SH: Ahhhh, Mililani. I don't know if you would call it a fond memory, but I remember Mililani received the first All-American City Award in Hawai‘i in 1986. The National Civic League recognized our community because we kind of banded together to get the DDT in our water cleaned up.

LT: Interesting. So you grew up around community activism. That probably wen shape you little bit, yeah. Um, Stacey, I not sure what for call you. So what title encompasses all da creative Nisei veteran projects that you do?

SH: You could just say “Friend of the Vets.” That’s what they put on my name tag when I go to Nisei veteran events. They ask, “Who are you with? Are you with Club 100, 442, MIS?” But over the years, I’ve helped everybody, you know. So I say, “Ah, just write ‘Friend of the Vets.’”LT: How old you wuz when you first heard about da contributions of da Nisei veterans during da war?

SH: As a kid growing up, I always heard about the 100th and the 442nd because my great-uncle Ko, Koichi Fukuda, he was my grandpa’s younger brother and he was original 100th Battalion, and so my dad would tell me, Uncle Ko and those guys from the 100th, they’re heroes you know, and my dad would continue telling me their stories. But as a kid, I think I kind of took these things for granted. And so I was like that’s such ancient history, you know, like, I’m a girl, I’m nine, I don’t care.

LT: Do you remembah da precise moment you realized you wanted for dedicate your life to helping to tell da stories of da Nisei veterans?

SH: In 1999 or 2000, I was a software engineer with my own media company and the State was giving high-tech tax credits to all the IP industries and they added film. And so I had remembered a play that I saw at UH’s Kennedy Theatre about the Nisei veterans. It was by Ed Sakamoto and it was called Our Hearts were Touched with Fire. Devon Nekoba played the lead. So I hunted down the playwright who was from Hawai‘i, but lived in LA, and I said, “Hey, what if we turn your play into a movie?” He was like, “Okay. But I’m going to be very difficult to work with.”

So there was this California Civil Liberties Public Education Program that was giving out grants and so we applied for a grant from them. I sent them a DVD of the play and the administrator of that fund, who was a katonk [Japanese person from the continental US], she said, “Well, I like what you’ve got. This is good. But I just have some notes for you. As a mainland Japanese American there are some parts with Pidgin where I got lost. So you might want to tone down the Pidgin.”

So I went back to Ed and he just kind of blew up. He was like, “Tone it down? It’s already toned down! If anybody changes my play, it’s going to be me!” So that was like the trial by fire, learning what it’s like to work with creatives. It’s his baby. And so I said, “If you’re not going to be able to take notes from people who have the funds, then I don’t know that we can work together anymore.” So we parted ways. That was really sad for me.

LT: Who you grateful to in your journey in becoming such one strong advocate for Nisei veterans?

SH: Oh, it’s many vets, but most of all Eddie Yamasaki and Goro Sumida. They just took me in and told me all kinds of war stories. They introduced me to everybody, whoever they thought might be able to help me. Because they were such well respected veterans, when they said, “Hey, meet Stacey, she’s working on this thing to help us and we trust her,” it gave me credibility.

They were so friendly, warm, loving, and supportive of everything. They treated me like family. They helped me every step of the way with all my projects. They both have passed and I miss both of them. [Tearing up] I’ll be grateful to them for the rest of my life.

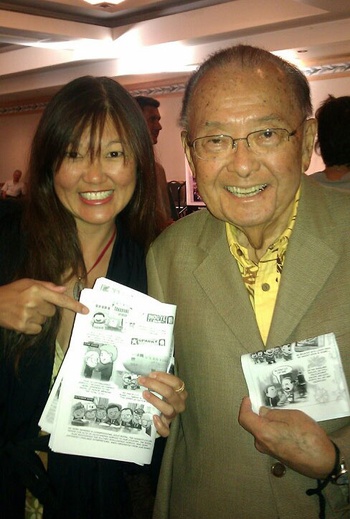

LT: So in 2012 you wrote and published one graphic novel called Journey of Heroes: The Story of the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team. So what prompted you for create one comic book?

SH: After Ed Sakamoto and I parted ways, I still wanted to make a movie about the Hawai‘i AJA experience. But I didn’t realize how impossible it was to make a movie. I hired a writer to write a whole new original screenplay. Then another writer. And then a third writer who had made off with a lot of my personal cash and he hadn’t done any work. So I was just sort of depressed, like, what am I going to do because I was stuck with all these scripts I couldn’t work with. And so my filmmaker friend Titus Chong said, “Why don't you just write the script? I can help you.”Then in 2007 the economy tanked and I’m like, “Man, how am I going to make this movie? Because nobody has any money.” That’s when I got the idea for the comic book. Because a comic book is so much more bite-sized. It’s still a big project, but you need way less people and way less money. And I didn’t even know how I was going to do the art and that’s when I met Damon Wong. And he was like, “I draw really good. Why don’t I just draw it for you?” So that’s how Journey of Heroes happened. We published it in 2012 and I kind of like to say it’s the CliffsNotes of the story of the Nisei vets.

LT: Da graphic novel stay drawn in one cute chibi style. Do you tink that might shield kids too much from da harsh realities of war?

SH: Right, so that actually addressed a huge problem that I was having because originally it was supposed to be realistic style. But then the plan had always been to donate half the print run to public schools and libraries. And I was kind of anxious about that because I didn’t want angry parents calling me saying, “Hey, why did you traumatize my kid?!”

LT: You wen write and produce da 2018 feature film Go For Broke. Now that I know about your past attempts—how come you wanted for try AGAIN?

SH: So back in 2007, I was awarded a grant in aid. But Governor Linda Lingle’s administration never released the money, and so it lapsed. Then in 2012, at Senator Daniel Inouye’s funeral, I saw my friends from the State House and the State Senate and they said, “Stacey, send your proposal through again. We got a Democrat governor now. We'll rubber stamp it.”

But I have to say that I don’t think that the movie would have happened without the comic book because the comic book was sort of like a proof of concept. The veterans were behind it, Senator Inouye wrote us a letter for it, the 442 Foundation wrote the Foreword, so it was sort of like all these endorsements.

And that’s how the movie happened. The legislature allotted the funding. The storyline of the movie is the fight to fight. December 7, 1941 sucked for all of America, but especially for Japanese Americans because they were looked upon as if they were the enemy and people wondered who they were gonna side with, but to the Japanese Americans it was never a question at all.

LT: Just last year in 2024 you wrote one children’s picture book, The Story of Lucy: Mascot of the 442nd RCT Medics. Try talk about that one.

SH: Okay, so it was actually COVID time and all the comic cons were canceled. A couple of friends of mine, Michael Cannon and Jon J. Murakami, were like why don’t we do an online comic con and we’re going to do a panel that focuses on Japanese American stories and we’re gonna have you with Disney animation artist Willie Ito.

We had such a blast. Willie and I just got along so well. Because he was talking about his work on Disney’s Lady and the Tramp and his work at Hanna-Barbera where he was the co-creator of Hong Kong Phooey... notice these are all dog characters... I just kind of asked him, “Hey, I don't know how busy you are or if this is of any interest to you, but I got this dog book that I’ve been wanting to make.” And he just started talking about something else so I thought he wasn’t interested.

Then a couple of years later we met in person at the Maui Comic Con and he gave me a great big hug. And he was like, “Stacey! I haven’t been able to get your dog book out of my mind. Are we going to do it?” And that’s kind of how it happened. And so I flew to LA four times last year and we worked on the book.The story is about the 442 Third Battalion medics who adopted a puppy in Luciano, Italy. They named her Lucy and they took her all over with them throughout the war and brought her back to Hawai‘i after the war. So she saved a lot of their sanity, you know. Lucy was a comfort animal before there even was that term.

LT: In highlighting war heroes for your projects, how you avoid glorifying war?

SH: It’s not glorifying because from being so close to the vets, I know how war has affected them and how awful it is. Nobody wants to get into a war because everybody loses. They all say that. There are no winners in a war. Even if you win, you still lose because you lose so many friends. That’s why I make sure to describe how truly awful war is. Seeing your friends die right there in front of you and not being able to do anything about it, that’s probably the worst thing in the world.

LT: Whyzit important young people know about da early first and second generation Japanese American experience?

SH: I think that they need to know how much adversity the Issei and Nisei overcame because we have it so easy now. You can’t appreciate something if you don’t know anything different. That’s why it’s important to tell these stories because it was really different 100 years ago. We should be grateful for all the opportunities we have today. It’s because of the men and women who came before us.

© 2025 Lee A. Tonouchi