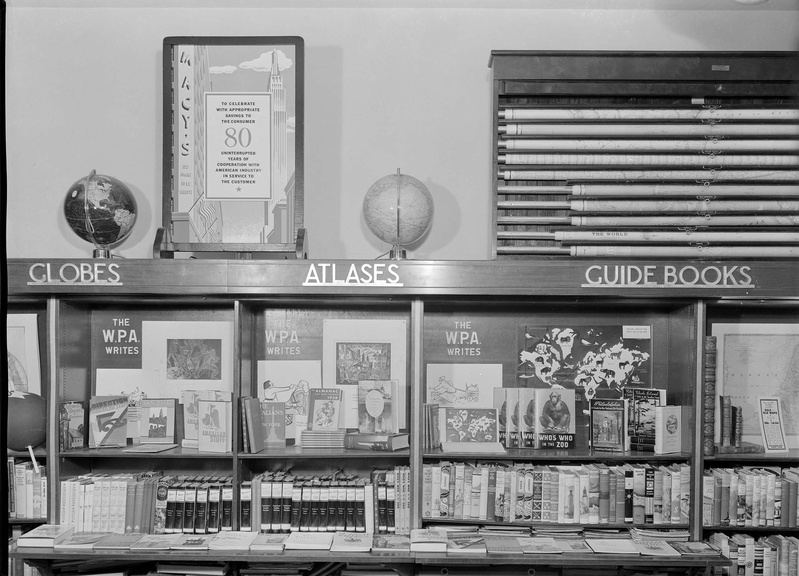

Beyond making the WPA guidebooks, FWP workers in various places were hired to do special assignments, notably interviewing ordinary Americans and collecting folklore. The most famous and valuable aspect of the oral history project was the large-scale series of interviews that FWP researchers conducted with elderly African Americans about their experiences under slavery in the antebellum South. Some oral history projects included Asian Americans. The Northern California unit produced anonymous oral histories of Asian immigrants (including the eminent Japanese American artist Chiura Obata). An interviewer in Mobile, Alabama interviewed the Japanese immigrant nurseryman Kosaku Sawada about his work life, including his youthful experience as a rice farmer in Texas and his development of hybrid camellias.

Interestingly, the most penetrating examination by FWP researchers of ethnic Japanese business and social life in a single community was undertaken, not in any West Coast city, but in New York City. During the period 1936-37, the local FWP division in New York created units on different “racial” and ethnic groups in the city. (The African-American unit, based in Harlem, was directed by the famed novelist Richard Wright).

Another unit was formed to study “oriental” groups. It was directed by Seunghwa Ahn, an expatriate Korean intellectual who was a graduate of Occidental College and American University. The staff was composed of a half-dozen white American writers, notably Jewish intellectuals such as Nathan Ausubel (future author of the classic anthology A Treasury of Jewish Folklore.)

The FWP “oriental” studies are fascinating to read now for the information they provide about Asian communities in New York, a unique cosmopolitan population center that was far from the West Coast in both geographical and sociological terms, and to a lesser extent for the aspects of community life and labor that they leave out.

As elsewhere, the largest fraction of material on “Orientals” pertained to Chinese Americans. FWP researchers compiled a large series of sociological reports on Chinese restaurants and curio shops, Chinese laundry associations, newspapers and religious groups. The principal author of these reports was a mysterious figure named Thomas Chow—whose name appears nowhere else in census reports or professional literature, and which may inferentially have been a pseudonym.

The unit took up the study of New York’s Japanese, though on a much smaller scale. “The Japanese also live in no section of the city in numbers large enough to constitute a colony. But although there is no Japanese colony here, there are Japanese newspapers, restaurants, stores, banks, and other manifestations of a Japanese population in the city which more than compensate for their small numbers.” Researchers produced memos on such topics as Japanese art, business firms, restaurants, and curio shops, which were then interpolated into overview articles. The reports are precious for the insight they offer into how white observers on the East Coast viewed ethnic Japanese in the last years before the Pacific War destroyed American-Japanese relations.

The first part of the “Japanese” study was on Japanese businesses. It included a memo by Seunghwa Ahn on “Important Japanese Commercial Houses in New York.” Ahn mentioned that the giant Mitsui company, which was the biggest Japanese firm in New York, dominated Japanese trade. Mitsui Company imported raw silk tea and camphor and exported cotton, petroleum and copper. The same conglomerate also ran the Mitsui bank and the Mitsui freight company.

Another conglomerate in New York was Mitsubishi, with offices of the Mitsubishi Company and the Mitsubishi bank. The city was also home to branches of the Yokohama Specie Bank, which specialized in Japanese securities, and the Nippon Yusen Kaisha Line, a steamship company. Ahn similarly contributed a pair of essays on silk. In “The Story of the Silk Trade in New York,” he explained that silk was an essential export of Japan: “Over 30 percent of the total foreign trade of Japan is with the U.S. Raw silk makes up about 90 percent. In 1935 the value of this commodity was over 90 million dollars. About 70 percent of this raw silk comes to New York. ”

Japanese exported silk in competition with silk from China. While Chinese silk was more in demand by European buyers because of its better color, Ahn explained, the Japanese product was more popular on the New York market because of its finer quality. The largest part of this silk was used to make ladies’ hosiery.

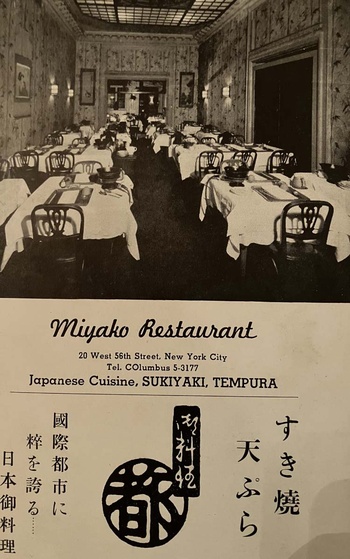

There also was a set of memos on Japanese shops and businesses. “Thomas Chow” contributed an article on Kuwayama and Co., an importing firm at 74 West 47th Street. “The firm caters to the half-a-dozen Japanese restaurants in the city and to Americans who occasionally take a fancy to Oriental cooking. Speaking of Oriental cooking, the Japanese “Sukiyaki” or “Gyuname” is a much simpler yet more pleasant affair than the preparation of Chinese Chop Suey or Chow Mein.”

Chow noted that there was no perfect sukiyaki without sake being included, but that the small volume of business in wine meant that Mr. Kuwayama did not have an importer’s licence and did not stock it.

“However, one can obtain Koji, a special kind of yeast, from Mr. Kuwayama and simply mix it with water and let it stand a week or so and there it is, Sake….When one has a Chinese appetite and for one reason or another does not want to go to a Chop Suey place, one may eat at home chop suey cooked in Japan. Yes, Mr. Kuwayama carries a whole list of preserved and cooked foods, both Japanese and Chinese, in tins and jars, from fish, vegetables, fruits to delicacies like ginger, beancustard (sic), candies and whatnot.”

An interesting piece of information shared in Chow’s article was that the Kuwayama firm was the wholesale importer of “Aji-no-moto.” “‘Aji-no-moto’ is a powdered seasoning made from wheat, which when added to soup or any other dish - gives an odorless yet delicious taste. It is widely used In American restaurants. It was an indispensable article in the chop suey houses, but since the Chinese boycott against Japanese goods, several brands have been produced In China with processes similar to ‘Aji-no-moto’ and serve as substitutes in the Chinese restaurants in this country.”

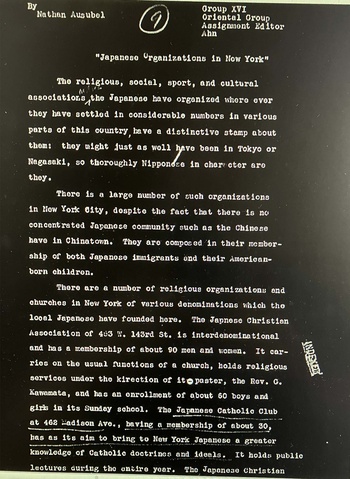

A second group of essays, directed by Nathan Ausubel, focused on Japanese associations in New York. This section is especially intriguing to study for its evolution. The final version started with an affirmation of the essentially “Oriental” nature of Japanese community life:

“The religious, social, sport, and culture organizations… have a distinctive stamp about them: they might just as well have been in Tokyo or Nagasaki, so thoroughly Japanese in character are they.” Yet Ausubel’s original draft, excised for the final version, explains this structure as a product of Japanese exclusion, not their innate nature: “The legal and social restrictions imposed upon the immigrant Japanese in America, thus barring him from a normal and constructive participation in the community life about him, have made him turn in greater dependence to the society of his fellow Japanese and to the culture of his fatherland.”

Similarly, the draft notes the presence of Nisei:

“There is a large number of such organizations in New York City, despite the fact that there is no concentrated Japanese community such as the Chinese have in Chinatown. They are composed in their membership of both Japanese immigrants and their American-born children.”

Again, a passage excised from the final draft outlined the tragic reason that Nisei in New York joined these exclusive clubs and churches:

Born and bred in this country they very naturally have come to regard themselves as just as good Americans as the native sons and daughters of their white neighbors. Unfortunately, social discrimination hedges them about everywhere they go. While they may join a Y.M.C.A., they may not use the swimming pool; while they may be welcomed to membership in certain churches there is instituted against them the numerus clausus. [“Numerus clausus” is the term for the racist quotas in Europe that limited the number of Jewish students admitted to universities].

The essay listed a series of religious organizations and churches for local Japanese: The Japanese Christian Association of 435 W. 143rd Street (interdenominational); The Japanese Catholic Club; and The Japanese Christian Institute (Dutch Reformed Church). The largest institution was the Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church and Institute at 323 West 108th Street, with a membership of 121 people. The Church ran a Young People’s Society, a Sunday school, and a Japanese Language school for Nisei. “The Church frequently arranges lectures on religious subjects and on various aspects of Japanese art. It also publishes a bulletin, and has a library of both Japanese and English books.”

The memo noted the paradox that, while a majority of Japanese in New York were of Buddhist origin, the city housed only one tiny Buddhist temple, located at 63 West 70th Street, the majority of whose worshipers were white Americans! (In 1938, Rev. Hosen Seki would found the New York Buddhist Church, with a largely Japanese congregation).

There was also a proliferation of social clubs, including the Nippon Club at 161 W. 93rd Street, the Japanese American Young Mens Association. at 9 W. 98th Street, and the Japan Society (whose address was not listed), which the memo stated was composed of about 500 Americans and 100 Japanese businessmen.

Ausubel stated that the leading community organization, which served as an influential public voice for the group, was the Japanese Association at 1819 Broadway. “It is a benevolent and cultural body and its principal aims are to inculcate a love for Japan and Japanese culture among the Japanese in New York, and to promote better understanding and foster better relations between the Japanese and their fellow Americans.”

The memo added that the only labor group within the local community was the Japanese Workers Club, 144 2nd Avenue. “It has fifty members and takes a clear stand on political questions. It is, incidentally, the only Japanese group which ventures an opinion on politics here.”

Ausubel likewise noted the proliferation of sports clubs. “There are two Jiu-Jitsu Clubs, one tennis club, four golf clubs, one archery club and one fencing club. The Nippon Archery Club…at 243 W. 68th St. has a membership of about 40 businessmen. The Japanese Fencing Club at 114W. 48th St. is devoted to the ancient and highly revered Japanese forms of fencing and wrestling known as kendo and judo”—both of which had a deep religious significance. Finally, he listed a Japanese Artists Club on 14th Street and a Japanese music club at 1831 Broadway, formed to perpetuate Japanese artistic and musical traditions and tastes among the New York Japanese.

The third set of memos was on “Japanese Art.” It included an extended essay on Japanese art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Philip Hurn, a onetime screenwriter, contributed extended biographical sketches of the artists Yasuo Kuniyoshi (“Kuniyoshi the Painter”) and Isamu Noguchi (“Noguchi The Nimble”). There also was an essay on Japanese restaurants in New York, with an extended passage on the preparation of sukiyaki, the chief dish they offered.

In sum, the FWP memos presented Japanese in New York as affluent and modern, and well-integrated into mainstream society. It ignored the lives of a large majority of residents, who worked as domestic workers and manual laborers, resided in working class areas or with their employers, and lacked the time and resources to enroll in clubs and social groups.

© 2025 James Sun and Greg Robinson