The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was a short-lived but historically significant federal agency. Founded in 1935 as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and directed by Harry L. Hopkins, its goal was to create and finance public-sector jobs to give work to millions of unemployed Americans during the Great Depression. While most of these jobs were unskilled, there were divisions created for skilled workers, including artists and intellectuals—“they are workers, too,” FDR is said to have remarked. To give work to creative people in diverse fields, WPA directors created the Federal Arts projects.

Although Japanese Americans, like other Asians, experienced discrimination in public sector employment, WPA directors did hire several talented individuals. May Matsumoto worked for the WPA’s division of research as an interviewer for a labor market survey, and canvassed homes in Japantown to collect data on family employment and unemployment.

The actor Goro Suzuki, who later went on to fame under the stage name Jack Soo, made his theatrical debut in San Francisco in the Federal Theater Project play “These Few Ashes.” The San Francisco Theater History project hired Nisei writer Eddie Shimano to produce volumes on the history of the stage in the city. Shimano also worked on (and may have ghostwritten) a volume on painter Chiura Obata for an art history project.

The New York-based Issei journalist Bunji Omura worked with his wife Martha as WPA translators—since Mrs. Omura, a white American, spoke no Japanese, this may have been a means of getting around official bans on hiring of aliens.

Nikkei painters started working for the government, notably on murals for public buildings. Even before the WPA was created, Takeo Edward Terada was commissioned to paint a section of the Coit Tower murals in San Francisco. Under WPA sponsorship, Issei painter Sakari Suzuki produced a mural, “Preventative Medicine,” for Manhattan’s Willard Parker Hospital, while Eitaro Ishigaki painted a Black history mural for the Harlem Courthouse (where his rendering of Abraham Lincoln was criticized as looking “negroid.”)

Hideo Date was hired for work on a mural at Terminal Island in Los Angeles—then removed from the project after Pearl Harbor. Some mural artists were women. Miné Okubo painted murals at Fort Ord and Servicemen’s Hospitality House in Oakland. Violet Nakashima worked on the Pictorial Histories of Mount Diablo State Park and Big Basin Redwoods State Park. Meanwhile, established artists such as Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Bumpei Usui, Chuzo Tamotsu, Isamu Noguchi, and Riyo Sato were hired by the Federal Arts Project to produce smaller-scale paintings and sculpture, which were displayed in WPA art shows.

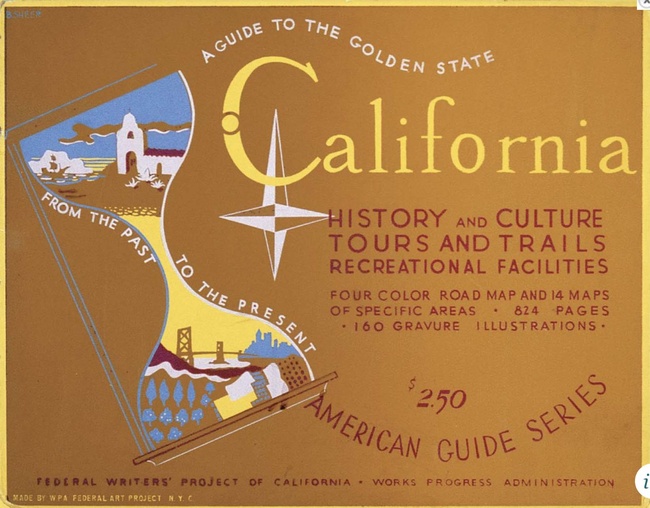

Another notable WPA division was the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), which employed novelists, poets and journalists. The FWP’s chief assignment was to produce the now-famous WPA guides. These were travel guides to the then-48 states of the Union, plus certain major cities. In keeping with its directors’ diverse vision of American society, FWP projects included Japanese Americans and other Asians, but within narrow limits. An examinational of the guides reveals their woefully inadequate coverage of Nikkei.

To begin with, there was no discussion, in any WPA guide, of Japanese in the territory of Hawaii, the nation’s most concentrated and consequent ethnic Japanese population, because there was no Federal Writers Project division created there.

Meanwhile, the Nikkei presence on the West Coast passed largely unrecorded. The FWP writers who produced the WPA Guides to Oregon and Washington had little to say about their states’ Japanese residents. The Oregon guide devoted a single page to community history:

“Oregon's 4,958 Japanese are engaged chiefly in farming, gardening and small commercial enterprises. A few are employed by industry or in hotels and restaurants. As farmers, their ambition to own land raised issues of national and international import. A quarter of a century ago early orchardists of the Hood River Valley hired Japanese laborers to clear land. The Oriental stump-diggers saved money and began to buy orchard land of their own, and to build homes. The act was resented and in 1917 a Hood River senator introduced a bill in the Oregon legislature, prohibiting Asiatics from owning land in the state.”

With what seems now excessive optimism, the Guide downplayed continuing dicrimination:

“Of late the anti-Japanese ownership laws of Oregon have been much nullified, because Japanese children, born in the United States and guaranteed citizenship by the Federal Constitution, have acquired land under white guardianship. Thus Japanese today successfully own land in Oregon and till it with profit since they are expert gardeners and orchardists.”

The section on Portland made only a single reference to the city’s Japanese residents, mentioning the Buddhist temple they erected.

The Washington State guide was even less inclusive. Though “the guide to the Evergreen state” did include a photo (from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer) of “Japanese” girls dancing at a July 4th celebration, its text had more to say about Japanese oysters than Japanese communities within its borders. There were glancing references to truck gardens and one to chick sectors. Still, the existence of Seattle’s International District community, and the buildings in it, were passed over in silence.

The long history of anti-Japanese racism in the state was reduced to a single sentence obscured by an inaccurate narrative, with no mention of Washington’s Alien Land Act: “Chinese, barred by Federal Exclusion Acts of 1881 and 1888, were further discouraged by anti-Chinese riots and demonstrations in the middle eighties. A subsequent wave of Japanese immigration was halted by Federal legislation.”

Nikkei were further passed over in other state guides. The Arizona guide, prepared by the employees of the state teacher’s college at Flagstaff (today’s Northern Arizona University), made no mention of Japanese whatsoever. The New Mexico Guide stated only that there were Japanese in Gamerco, with no further information given. The Colorado state guide, apart from a few bare references to the presence of Issei farm workers, only mentioned the state’s Nikkei communities once, in a description of the Buddhist Church in Denver. The text noted that it was “the only church of that faith between Salt Lake City and New York City, which serves 2,000 communicants scattered through Colorado and adjoining states.” The origins and lives of that enormous congregation were nonetheless unexplored.

While Utah had the most substantial Japanese population outside of the West Coast, the state’s guide made little acknowledgment of their presence. First, Utah’s long anti-Japanese history was reduced to a sentence: “Lynching of a Japanese in 1884 [in Ogden] indicated that better police protection was required.”

Beyond statements that “the occasional Japanese” could be found in places such as Salt Lake City, Logan and Helper, those unfamiliar with the history of Nikkei in Utah would have found little in the guide to enlighten them—indeed, the only concrete indication that it provided about Salt Lake’s historic Japanese community was a Japanese cemetery listed among the city’s burial grounds.

The sole community site referenced in the Utah guide was Ogden’s Jodo Shinshu Buddhist temple, which was described in a paragraph:

“[Located] in a remodeled brick store building, [it] was occupied as a temple in 1937. When the panels are opened the subdued glow of incandescent lights and candles creates a hushed oriental effect. Worshipers in passing before the shrine clasp their hands before their faces in adoration. Services are conducted mainly in Japanese. The congregation rises for singing, but remains seated during the other services…When Japanese motion pictures are presented in the temple, about four times a year…the pagoda (sic) is wheeled into a corner out of sight. Weddings and funerals are usually held in the evening; visitors are permitted.”

The Utah guidebook made two rather random mentions of Japanese. First, in a discussion of the farming community of Francis, the guide noted a granite marker that “honors Masashi Goto, a Japanese aviator on an attempted globe-girdling flight, who crashed nearby in 1929.” The Section on Sunnyside quoted an interview with Lucile Richens:

“We children used to go down to Jap town after school to watch the Japanese fly kites. . . .They used to make wooden men, painted in bright colors…joined at the elbows, shoulders, waist and knees and worked by a windmill in such a way that, when the wind blew, it looked like the wooden men were turning the windmills.”

In the WPA guide to California, the center of Japanese American population on the continent, discussion of the Nikkei presence remained shockingly brief. True, as in Oregon, there was a nod in the book’s introduction to the history of anti-Asian racism and “yellow peril” thought in the state:

“The Japanese, imported in increasing numbers by large agriculturists to take the place of the Chinese as farm workers, had begun to settle as farmers and tradesmen, managing their small holdings so thriftily that soon they were displacing white workers and farmers. Although they numbered but 14,243 in 1906 — and for many years had been excluded along with other Orientals from the privilege of naturalization— military and patriotic groups, merchants' associations, and labor organizations combined to raise the cry: ‘California shall not become the Caucasian graveyard.’”

The guidebook mentioned the San Francisco School board’s segregation of Japanese pupils, and the 1913 Alien Land Act (though not the history of school segregation or laws against interracial marriage). Still, as in Oregon, California FWP writers disingenuously presented such racism as a thing of the past:

“Another influence promoting the unification of the labor movement has been the gradual disappearance of the racial discrimination that once characterized it. The anti-Chinese and anti-Japanese agitation that kept American and Oriental workers apart has largely vanished…The hostility once directed against Chinese, Japanese, or Mexican workers is more apt to be directed now against native-born Dust Bowl refugees when attempts are made to use their labor at wage rates that endanger general California standards.”

Meanwhile, there was hardly any coverage devoted to Japanese community life and institutions in the California State Guide. Apart from the “Japanese fishing village” in Wilmington, near Terminal Island, the only Japanese community institution which it recommended to visitors was the Buddhist Temple in Fresno:

“Erected in 1902, [it] is a three-story building with stucco finish, scrolled tile roof, and an ornamental carved entrance of white wood with swastikas set into the portico. Some of the sacred ashes of Buddha, brought from India, are guarded in the temple. The congregation of 700 is served by two Japanese priests. Services are held Sunday evenings at 8 o'clock before an altar finished in gold leaf. Special services in April celebrate the birth of Buddha.”

The Japanese community of “Little Tokyo” in Los Angeles received a bare two sentences:

“The 21,000 Japanese, many of them American citizens, have their own shops, restaurants, native-language schools and newspapers, chamber of commerce, and American Legion post, in the district centering on E. First Street, between Los Angeles Street and Central Avenue. Many of the Japanese are engaged in trade, particularly in the fruit and vegetable markets.”

The only site of interest it catalogued was the Buddhist Temple (which would later be incorporated into the Japanese American National Museum). “The Japanese Temple was built in 1925. The temple, a three-story brick building, is reached by stairs leading to the second floor. The temple altar is intricately carved and covered with gold leaf.” Shockingly, while the guide noted the Japanese tea garden in San Francisco’s Golden Gate park, the city’s sprawling “Japantown” with its temples and shops, was not even mentioned.

Even the Los Angeles and San Francisco City guides devoted only a single page to their cities’ respective Japanese communities. While journalist Carl Wilhelmson put together an extended report on “Racial Elements and Folklore” for the San Francisco project that included an extended section on “Little Osaka,” and Nisei writer Jo Morisue contributed a set of memos on Nikkei community life, hardly anything made it into the final city guide.

The first part of this column was adapted from Greg Robinson and James Sun, “Eddie Shimano and Gerald Chan Sieg: Asian American Writers in the FWP,” in Sara Rutkowski, ed. Rewriting America: New Essays on the Federal Writers’ Project, Amherst MA, University of Massachusetts Press, 2022, pp. 210-229 (with James SUN)

© 2025 James Sun and Greg Robinson