In London, rail passengers are warned by the phrase “mind the gap” to take proper caution when crossing between the train doorway and the station platform edge. Similarly, in the book under review, co-editors Eiichiro Azuma and Kaoru Ueda (both connected with the Japanese Diaspora Initiative at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution) counsel readers not to skip over the crucial developments of the 1930s when exploring the Japanese American historical experience extending from the pre-1924 exclusionary immigration policy to the mass incarceration of Nikkei during World War II.

Thus, they have assembled a cadre of eminent contributors of transnational and migration scholars from the mainland U.S., Hawai‘i and Japan, to contribute 10 articles to their landmark anthology that collectively illuminate both why the decade of the 1930s has been previously neglected and how this abandonment is now being addressed and redressed.

The brevity of this review has mandated that, notwithstanding the acuity of all 10 of the volume’s bountiful articles, I am forced to limit my critical attention to only the first and most essential of them: Yasuo Sakata’s “Fifty Years after World War II and the Study of Japanese American History: The Untold 1930s.”

In Sakata’s reprise of his 1995 research paper, he states his reasons why scholars have not chosen to research the 1930s. First and foremost was that in the wake of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, the leadership of the Japanese American community, the Issei generation, which was denied American citizenship status, was ignominiously disparaged as enemy aliens. Fearing for their safety in a pervasive anti-Japanese climate, Issei organizations, associations, selected families and individuals, and most especially prominent public spokespersons, according to Sakata, “likely attempted to burn, bury, or throw into the sea documents that might be taken as evidence of their loyalty to Japan, their motherland and new enemy nation” (p. 25).

Secondarily, even after the war when earnest attempts were made to remedy this situation, such as the creation of the ambitious Japanese American Research Project, which included substantial archival material donated by Issei and in-depth oral histories with 1,000 randomly selected Issei, the former were conspicuously sanitized and the latter undermined by many leaders choosing not to be interviewed to avoid rekindling anti-Japanese sentiment and others remaining silent or evasive about controversial events and topics. What this situation came to mean for historical researchers vis-à-vis the 1930s decade was that it “would become not only an untold but also a distorted decade” (p. 35)

Third and finally, this state of affairs became compounded during the 45-year fight for Japanese American redress and reparations when it was feared that bigoted Americans in and outside the U.S. government would capitalize upon evidence of Issei loyalty to their ancestral country to deny Nikkei restitution for their unjust World War II incarceration.

For Sakata, as explained by co-editor Eiichiro Azuma, “rescuing the 1930s from historical obscurity requires both discovery of immigrant primary source materials and close and critical reading of them” (p. 6).

The other co-editor for this volume, Kaoru “Kay” Ueda, in her aforementioned role at the Hoover Library and Archives, has dedicated herself to making this rescue mission more achievable. In addition to acquiring pertinent archival materials on Japan and overseas Japanese for educational and scholarly use, she continues to curate and develop the Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, the world’s foremost online full-image open-access collection of pre-World War II overseas Japanese newspapers.

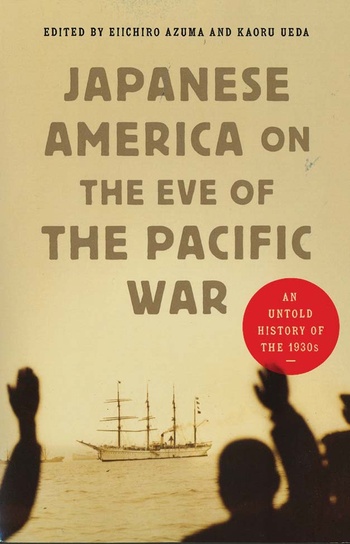

“Japanese America on the Eve of the Pacific War” is a work of monumental importance, not only in terms of its scholarly contents, but also because of the overriding cause it champions.

JAPANESE AMERICA ON THE EVE OF THE PACIFIC WAR: AN UNTOLD HISTORY OF THE 1930S

Edited by Eiichiro Azuma and Kaoru Ueda

(Stanford, Calif: Hoover Institution Press, 2024, 310 pp. $29.95, paperback)

This article was originally published in Nichi Bei News on July 18, 2024.

© 2024 Art Hansen, Nichi Bei News